Head and neck

Vol. 45: 111TH CONGRESS SIOECHCF - OFFICIAL REPORT 2025

Prognostic significance of surgical margins in laryngeal cancer treated by transoral laser microsurgery: a systematic review and meta-analysis

Abstract

Objective. To evaluate the prognostic significance of surgical margins in patients undergoing transoral laser microsurgery (TLM) for laryngeal squamous cell carcinoma (LSCC).

Methods. A comprehensive literature search was conducted in PubMed/MEDLINE, Cochrane Library, Scopus, and Google Scholar following PRISMA guidelines. Studies comparing oncologic outcomes between positive and negative resection margins were included. Hazard ratios (HRs) for local control (LC), disease-free survival (DFS), and overall survival (OS) were extracted and pooled using a random-effects model to account for inter-study variability.

Results. A total of 26 studies, including 5,463 patients, met inclusion criteria. The pooled log-HR for DFS was 0.93 (p < 0.05), indicating a significantly higher risk of recurrence in patients with positive margins. However, no significant differences were observed for LC (log-HR = -0.76, p = 0.59) or OS (log-HR = 0.16, p = 0.40).

Conclusions. While positive surgical margins significantly impact DFS, their effect on LC and OS remains uncertain. Further prospective studies are necessary to refine treatment guidelines and optimise oncologic outcomes.

Introduction

Laryngeal squamous cell carcinoma (LSCC) is one of the most common head and neck malignancies. Treatment selection is primarily guided by the extent of the primary tumour. Transoral laser microsurgery (TLM) and radiotherapy (RT) are the standard treatments for early and selected locally advanced cases, as both methods provide comparable local control (LC) and high rates of laryngeal preservation 1-4.

Ideally, tumours classified as T1, T2, and selected T3 should receive unimodal treatment. However, certain adverse pathological features may require additional therapy. One significant factor is the presence of positive surgical margins, which has been identified as a key prognostic indicator influencing LC and survival 5,6. Therefore, achieving tumour-free resection margins is a primary goal for surgeons, as it can help minimise the need for multimodal treatment and associated complications.

Interpreting margin status in TLM can present challenges due to several factors. First, there is a lack of consistency in how margin status is defined across the literature. Negative margins are generally defined as greater than 1 mm from the tumour, close margins as less than 1 mm, and positive margins indicate the presence of the tumour at the resection edge 7-12. Second, the incidence of positive margins associated with TLM can be as high as 50%. This may be due to the technical limitations of laser dissection within the narrow glottic space, which are influenced by anatomical and functional considerations 13,14. Additionally, studies have shown that in case of positive or close margins, up to 80-90% of patients have no residual disease upon revision surgery 5,15,16. This suggests that positive margins may often stem from tissue processing artifacts rather than represent true tumour persistence. In these situations, finding neoplastic cells during revision surgery seems to be a more reliable predictor of poor oncologic outcomes than the initial margin status alone 15.

Given the uncertainties surrounding margin assessment and its impact on oncologic outcomes, it is crucial to gain a clearer understanding of its prognostic significance to optimise treatment strategies. This study aims to summarise recent data to elucidate the prognostic importance of margin status in patients undergoing TLM for LSCC. The goal is to guide more precise surgical and postoperative management strategies, thereby improving oncological outcomes and reducing treatment-related morbidity.

Materials and methods

This study was conducted according to the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guidelines 17. Since all data were sourced from previously published papers, ethical approval or informed consent was not needed, and no review protocol was registered for this study.

Eligibility criteria

This systematic review was conducted using the PICOS framework: Patients (P), adult patients diagnosed with LSCC; Intervention (I), TLM using CO2 laser; Comparison (C), positive versus negative resection margins; Outcomes (O), LC, disease-free survival (DFS), and overall survival (OS); Study design (S), retrospective and prospective cohort studies, and randomised controlled trials (RCTs).

Studies were deemed ineligible if they were not in English, not available in full-text form, reported insufficient data or data were not extractable, consisted of subgroup analyses of patients from a larger study or presented overlapping patient cohorts, or the article type was either a review, case report, conference abstract, letter to the editor, or book chapter. No restrictions on publication date were imposed, but all articles had to be published in a peer-reviewed journal.

Data source and study searching

PubMed/MEDLINE, Cochrane Library, Scopus, and Google Scholar databases were comprehensively searched to identify relevant articles. The following search strategy was used for PubMed/MEDLINE: ((“larynx” OR “glottic” OR “subglottic” OR “supraglottic”) AND (“neoplasms” OR “cancer” OR “carcinoma” OR “tumour”)) AND (“lasers” OR “micro-laryngoscopy” OR “transoral surgery” OR “TLM” OR “TOLM” OR “TOLMS” OR “laser therapy”). This search strategy was then adapted to meet the specific search requirements of the other databases. Additionally, the reference lists of all included publications were manually searched to identify any further potential eligible articles. The last search was conducted on January 14, 2025.

Data collection process

Two authors (ER and ADV) independently conducted the literature search. Initially, all articles were screened for relevance by title and abstract. Next, the 2 investigators separately reviewed the full text of each publication that was deemed pertinent. Any disagreement during the assessment process was discussed until a consensus was reached. Data extraction from the included studies was performed independently by the same two reviewers using a structured form. The following information was recorded for each eligible study: first author, year of publication, study design, sample size, patient demographics, tumour subsite, tumour stage, type of cordectomy, margin status (negative, positive, close, or not assessable), follow-up duration, and oncologic outcomes stratified by margin status and/or adjusted hazard ratio (HR) values for the endpoints of interest (LC, DFS, and OS). Any discrepancy in data extraction was resolved by reaching a consensus.

Risk of bias and study quality assessment

Two separate reviewers (ER and ADV) independently assessed the methodological quality of the included studies using the reporting recommendations for tumour prognostic studies (REMARK) guidelines 18. This assessment considered 8 domains: inclusion and exclusion criteria, study design (prospective or retrospective), description of patient and tumour characteristics, definition of margin status, specification of study endpoints or outcomes, definition of the follow-up period, and identification of patients unavailable for statistical analysis (e.g., lost to follow-up). Each domain was rated as adequate (1) or not adequate (0), resulting in a total quality score ranging from 0 to 8, with higher scores reflecting better methodological quality. A score greater than 5 was considered indicative of globally adequate quality. A funnel plot was created using the effect size of each outcome to examine a potential publication bias.

Data synthesis and statistical analysis

Clinical measures were reported as provided by each study. A single-arm meta-analysis of proportions was conducted to summarise dichotomous variables by applying arcsine transformation to the data. Continuous variables were summarised through a meta-analysis of means using the generic inverse variance method. All data are presented with their corresponding 95% confidence intervals (CIs).

The primary endpoints were LC, DFS, and OS. LC was defined as no evidence of residual tumour or local recurrence during follow-up. DFS was defined as the time from treatment until the recurrence of disease or death. OS was defined as the time from the date of diagnosis (or the start of treatment) to death by any cause.

The impact of margin status was measured by the effect size of HR. HRs and their 95% CIs were extracted directly from each study if provided by the authors. Whenever both uni- and multivariable analyses were reported, HRs were extracted from multivariable models. Otherwise, they were indirectly estimated using the methodology described by Tierney et al. 19. Published Kaplan-Meier curves from each study were digitised using GetData Graph Digitizer (version 2.26; http://getdata-graph-digitizer.com/index.php), and survival data and follow-up times were extracted. Hence, the number of subjects at risk, adjusted for censoring at different follow-up times, was calculated to reconstruct the HR estimate and its variance. HRs were log-transformed before pooling effect size estimates. Cumulative log-HRs with 95% CI are presented for the reported outcomes, calculated through the inverse variance method. A log-HR > 0 indicated a higher risk of recurrence or mortality for patients with positive surgical margins compared to those with negative margins, whereas a log-HR < 0 implied a lower risk for patients with positive margins. A Forest plot was created for each outcome.

Cochran’s Q method and the I2 statistic were utilised to assess heterogeneity among studies 20,21. The I2 value indicates the percentage of variability across studies that is attributable to heterogeneity rather than to sampling errors. According to the Cochrane criteria, an I2 value of 0% to 30% suggests low heterogeneity, 30% to 60% indicates moderate heterogeneity, 60% to 90% reflects substantial heterogeneity, and 90% to 100% signifies considerable heterogeneity. Given that most of the studies included were observational, a random-effects model was employed to pool the study results, accounting for both within- and between-study variabilities. An influence analysis 22 was conducted to identify studies that may have had a significant impact on each outcome. Specifically, a leave-one-out meta-analysis was performed to evaluate each study’s effect on the overall result and the I2 heterogeneity.

Analysis of publication bias was performed by visual inspection of the funnel plot and calculating Egger’s regression intercept23, which statistically examines the asymmetry of the funnel plot.

Meta-analyses were conducted by Review Manager (RevMan, version 5.3; The Nordic Cochrane Centre, The Cochrane Collaboration) and R software for statistical computing (R, version 3.4.0; “meta” and “dmetar” packages). Statistical significance was defined as p < 0.05.

Results

Literature search results

Figure 1 presents a flowchart illustrating the study identification process and the reasons for excluding non-eligible studies. The initial search strategy and other sources yielded 6,979 papers, which were reduced to 5,812 after removing duplicates. Following a review of the titles and abstracts, 5,677 studies were excluded, and the full texts of the remaining 135 articles were assessed for eligibility. In the end, 26 studies were included in the qualitative analysis 6,8,10,16,24-45, and 15 were found to be eligible for quantitative analysis 9,16,24-26,28,29,31,32,38,39,41,44,45.

Study characteristics

The general characteristics of the studies are summarised in Table I. A total of 5,463 patients were included, with 92.8% being males (95% CI: 91-94.5). The mean age of patients was 64.2 years (n = 5,463; 95% CI: 62.6-65.8). Most patients were diagnosed with glottic LSCC, accounting for 98.3% of cases (95% CI: 92.3-100). In terms of tumour category, most patients (65.6%) had T1 tumours (95% CI: 50.5-79.2), while only a small percentage were diagnosed with advanced T-categories: T3 in 2.1% (95% CI: 0.1-6.8) and T4 in 0.1% (95% CI: 0-0.6). A total of 18 studies, which included 3,870 patients, provided detailed information on the types of cordectomy performed, based on the European Laryngological Society (ELS) classification. The most performed ELS cordectomy was Type III, accounting for 28.1% of cases (95% CI: 20.8-36.1). This was closely followed by Type V cordectomy, which constituted 22.2% (95% CI: 14.6-30.8). In terms of margin status, 65.4% of patients had negative margins (95% CI: 56-74.3), while 23.8% had positive margins (95% CI: 17.1-31.4), and only 1.6% exhibited close margins (95% CI: 0.2-4.2).

Methodological quality and risk of bias of included studies

REMARK criteria showed an overall mean score of 6.6 ± 0.4. REMARK scores of individual studies are shown in Table II. Funnel plots for each outcome are shown in Figure 2. Visual inspection and Egger’s linear regression test showed a symmetric distribution of the points in the funnel plot for LC (Intercept = -1.35, p = 0.59), DFS (Intercept = 0.26, p = 0.80), and OS (intercept = 0.44, p = 0.65), suggesting no evidence of publication bias.

Survival analysis

The mean follow-up time (reported for 4,675 patients) was 62.8 months (95% CI: 55.2-70.5). Six studies (on 1,025 patients) assessed the relation between margin status and DFS. The estimated pooled log-HR was -0.76 (95% CI: -4.21-2.69; p = 0.59; Fig. 3A). Substantial heterogeneity was measured between studies (Q = 31.97, p < 0.05). In particular, the between-study heterogeneity variance was estimated at τ2=7.4 (95% CI: 2.2-83.6), with an I2 value of 84.4% (95% CI: 67.6-92.4). A Baujat plot showing the contribution of studies to the overall heterogeneity is shown in Figure 4A. The association between margin status and DFS was assessed by 9 studies (2,655 patients). The estimated pooled log-HR was 0.93 (95% CI: 0.56-1.29, p < 0.05; Fig. 3B), with low between-study heterogeneity (Q = 8.86, p = 0.45). The between-study variance was estimated at τ2 = 0.05 (95% CI: 0-0.5), with an I2 value of 0% (95% CI: 0-62.4). A Baujat plot showing the studies’ contribution to the overall heterogeneity is depicted in Figure 4B. Finally, 6 studies (1,841 patients) investigated the relation between margin status and OS. The estimated pooled log-HR was 0.16 (95% CI: -0.28-0.6; p = 0.40; Figure 3C). Low heterogeneity was measured between studies (Q = 8.46, p = 0.21). In particular, the between-study heterogeneity variance was estimated at τ2 = 0.09 (95% CI: 0-1.04), with an I2 value of 29.1% (95% CI: 0-69.5). A Baujat plot showing the contribution of studies to the overall heterogeneity is shown in Figure 4C. Influence analysis identified no influential study on the cumulative log-HRs for any outcomes.

Discussion

This study aimed to evaluate the prognostic impact of positive surgical margins compared to negative ones in patients undergoing TLM for LSCC. Our findings revealed a pooled log-HR of -0.76 for LC, 0.93 for DFS, and 0.16 for OS. As mentioned above, a log-HR greater than 0 indicates a higher risk of recurrence or mortality for patients with positive margins, while a log-HR less than 0 suggests a lower risk. We found that positive margins were significantly associated with worse DFS (p < 0.05); however, no significant relationship was observed for LC or OS. It is important to highlight that the heterogeneity across studies varied considerably, which affects interpretation of the results. While the pooled log-HR for LC indicated an increased risk of local failure for patients with negative margins, the significant heterogeneity reduces the clinical meaning of this finding. Variability among studies, potentially due to differences in treatment protocols, follow-up durations, or criteria for margin assessment, limits the reliability of the outcome. In contrast, the DFS analysis showed minimal heterogeneity, indicating a consistent effect across the different studies. This consistency strengthens the clinical relevance of the pooled log-HR, which indicates a significantly higher risk of recurrence or death for patients with positive margins. The OS analysis exhibited moderate heterogeneity, suggesting some variability in outcomes, but this did not strongly compromise the interpretability of the results.

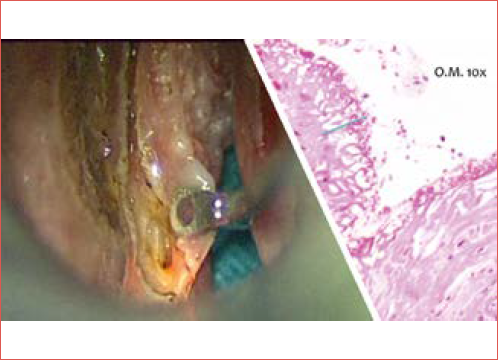

Pathological assessment of resection margins is the gold standard for determining the completeness of tumour excision. However, evaluating margins after TLM can be complicated by several factors, including the use of CO2 lasers and tissue shrinkage during sample processing 46,47. These issues contribute to a high rate of false positive margins, which have been reported in up to two-thirds of cases 46,48. Consequently, this can lead to unnecessary additional treatments in more than 50% of instances 9,15. Misinterpretation of margins may arise due to thermal artifacts, sampling techniques, and fixation-induced tissue loss, which can average 30-35% 7. CO2 laser resection creates a 0.3 mm zone of thermal damage around the incision, and variations in laser settings, such as spot size, power density, and delivery mode, further affect tissue alterations 49. Research indicates that CO2 laser can also cause submucosal thermal damage, further complicating evaluation of margins 50. The impact of laser settings is crucial; using lower power settings minimises specimen alteration and improves the accuracy of pathological assessment (Cover figure) 51.

Inconsistencies in how different studies classify adequate margins pose a significant challenge in interpreting margin status. This may be partly due to the unique anatomical and embryological characteristics of the glottic area. The absence of lymphatic drainage in this region, combined with the superficial and exophytic growth patterns of most glottic cancers, often sparing the underlying muscle, suggests that a more conservative approach may be justified. In contrast to other head and neck surgical specimens, where clear margins of at least 5 mm are typically considered adequate, a margin of 3 mm or even less free tissue from the neoplastic front can still yield good oncological results in conservative laryngeal surgery 13,15,16. Additionally, another challenge in interpreting margin status lies in the inconsistencies in defining margins as superficial or deep and whether they are single or multiple 39. Some researchers emphasise the importance of distinguishing between these types, as their prognostic implications differ 6,52,53. For example, studies have shown that the presence of a single superficial positive margin does not necessarily compromise LC and may not require a second-look TLM procedure 6. In contrast, multiple superficial or deep positive margins have been linked to poorer outcomes 6, thus necessitating additional surgery or adjuvant therapy.

Given these complexities, ensuring precise margin assessment is critical in optimising oncological outcomes. Frozen section analysis has emerged as a reliable technique during laser surgery of the larynx 54. The correlation between results of frozen sections and permanent histological examinations can be as high as 94% 54. Indeed, Fang et al. 33 found that the results of the initial frozen-section margin analysis are strong predictors of patient survival. Patients with malignant involvement detected in the initial resection margin by frozen sections showed a significant increase in recurrence rates within the first year. Notably, the early local recurrence rate was higher even when the cordectomy was promptly adjusted to ensure clear margins. One possible explanation for this observation is that a surgeon’s difficulty in identifying disease-free tissue based solely on the lesion’s clinical appearance may indicate patterns of field cancerisation or subtle intramucosal spread that are not easily recognisable.

Approaches to managing close or positive margins in laryngeal surgery vary among institutions. Options include planned early revision TLM, adjuvant RT, or strict endoscopic surveillance. The decision often depends on the number and type of positive margins. Some authors advocate for a second-look TLM even when only a single deep or superficial margin is involved 12, whereas adjuvant RT is generally recommended in cases with multiple positive margins 55. Interestingly, studies have shown that nearly 23% of patients undergoing second-look TLM for a single positive margin have no residual malignancy 12, suggesting that the risk may be overestimated in some instances. More broadly, approximately 60% of second-resection specimens do not reveal any residual cancer 56, raising questions about the necessity of routine second-look procedures. However, the likelihood of false positive margins decreases when multiple positive margins are present, making additional treatment more justifiable in these cases.

Patients with multiple superficial positive margins who do not receive further therapy face a significantly higher risk of recurrence. Some studies indicate that those treated with adjuvant RT have a markedly lower recurrence risk compared to those managed with observation alone 12. Consequently, when multiple positive margins are identified, additional treatment, whether re-resection or RT, is generally warranted to optimise disease control. Moreover, if a second-look procedure confirms persistent residual disease or positive margins, adjuvant RT is likely to further improve LC 55. In contrast, the available evidence suggests that a single superficial positive margin following TLM does not significantly impact LC, DFS, or OS, provided that patients undergo careful follow-up 6,12,57. Given these findings, a watchful waiting approach may be a reasonable alternative, but only in high-volume tertiary centres with access to advanced diagnostic tools such as MRI with diffusion-weighted imaging 58 and narrow-band imaging (NBI) using high-definition television (HDTV) systems 6,59.

For patients with deep positive margins, determining the most appropriate additional treatment requires careful consideration. While second-look resection is often preferred, its feasibility depends on whether negative margins can be realistically achieved. This largely hinges on the extent of the initial excision. If the initial procedure was a subligamental or transmuscular cordectomy, a transoral revision to widen the deep margin may still be a viable option 60. However, if the initial resection was more extensive – such as a total or extended cordectomy involving the inner perichondrium of the thyroid cartilage or part of the arytenoid – achieving clear margins through transoral resection is less likely. In such cases, the patient’s prior tumour characteristics and the specifics of previous surgery, particularly if assessed by the same surgical team, play a key role in guiding further management. When patients have undergone initial treatment at a different institution, planning an optimal re-excision strategy becomes more complex due to the lack of detailed surgical records, making outcomes less predictable. In such situations, open partial horizontal laryngectomy (OPHL) or RT may be considered based on factors such as patient age, performance status, and personal preference 12,55.

Adjuvant RT is a well-established option to improve recurrence-free survival and overall prognosis in cases with deep positive margins. However, it comes with potential drawbacks, including the risk of laryngeal radionecrosis and difficulties in detecting recurrences due to post-RT oedema and fibrosis. While radionecrosis is relatively rare, affecting 1-5% of patients, severe cases are irreversible and require total laryngectomy in most instances due to life-threatening laryngeal dysfunction 61. Notably, while radionecrosis can develop at any time, even decades after treatment, its incidence remains low, occurring in fewer than 1% of irradiated patients 62. Given these considerations, the decision to proceed with adjuvant RT must weigh the benefits of improved disease control against its potential complications.

This meta-analysis has several limitations. The primary limitation arises from the retrospective nature of the studies included, which may have introduced selection and review biases that could affect the outcomes analysed. Further prospective studies or RCTs are necessary to accurately evaluate the prognostic significance of margins in TLM. Additionally, the adjustment of multivariate analyses for clinical and pathological factors varied among the studies, and not all accounted for each type of margin status. The use of different statistical methods and cutoff values for margins further complicates the ability to draw definitive prognostic conclusions. Finally, due to the limited data reported in the included studies, our analysis could not stratify results based on the type and number of margins involved or disease staging. Similarly, it was not possible to conduct a subgroup analysis by margin type and histological subtype, which restricts the depth of our findings.

Conclusions

This systematic review and meta-analysis highlights the prognostic significance of surgical margins in TLM for LSCC. Our findings demonstrate that while positive surgical margins significantly correlate with decreased DFS, their impact on LC and OS remains uncertain. Given the risk of overtreatment in cases of false positive margins, careful consideration should be given to additional therapy, balancing oncologic safety with treatment-related morbidity. Future prospective studies should focus on refining margin assessment techniques and establishing evidence-based guidelines to optimise surgical and postoperative management in patients with LSCC treated by TLM.

Conflict of interest statement

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Funding

This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Author contributions

ADV: study design, article selection, writing, review drafting and critical revision; ER: article selection, data extraction; GPa, EC, GM: article search, critical revision; GS, GPe, AGr, MdV, AGa: critical revision of the article.

Ethical consideration

Not applicable.

History

Received: March 16, 2025

Accepted: March 31, 2025

Figures and tables

Figure 1. PRISMA flow diagram.

Figure 2. Funnel plot for evaluation of publication bias for (A) LC, (B) DFS, (C) OS.

Figure 3. Forest plots showing the pooled log-HRs for (A) LC, (B) DFS, (C) OS. The dashed vertical line represents the overall measure of effect.

Figure 4. Baujat plots showing the contribution of studies to the overall heterogeneity for (A) LC, (B) DFS, (C) OS.

| First author(year) | Studydesign | No. of patients(males) | Mean age(range) | T site | T category | Type of ELS cordectomy | Margin status | 5 y LC (%) R0/R+ | 5 y DFS (%)R0/R+ | 5 y OS (%) R0/R+ | FU months(range) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ahmadi (2023) 24 | Retrospective cohort study | 83(77) | 67.7 (42-94) | Glottic (n = 83) | T1a (41)T1b (42) | I (1)II (14)III (44)IV (4) | Negative (37)Positive (32)Close (14) | NA | NA | NA | 73.2 (63.6-94.8) | |

| Aluffi Valletti (2018) 25 | Retrospective cohort study | 308(291) | 65.2 (32-91) | Glottic (n = 308) | Tis (29)T1a (228)T1b (29)T2(22) | I (9)II (32)III (107)IV (102)V (58) | Negative (206)Positive (85)Close (17) | NA | 92/75.1 | NA | 68.3 (12-243) | |

| Ansarin (2017) 26 | Retrospective cohort study | 590(530) | 63.9 (28-89) | Glottic (n = 590) | T0(88)Tis (58)T1(315)T2(90)T3(36)Unknown (3) | I (32)II (196)III (204)IV (43)V/VI (108)Unknown (7) | Negative (369)Positive (142)Close (59)Dysplasia (18)Unknown (2) | NA | 88.9/81*88.9/72§ | 79.2/69.7*79.2/65.4§ | 72 (0-177) | |

| Blanch (2011) 27 | Retrospective cohort study | 107(104) | 63.3 (39-95) | Glottic (n = 104) | T2(81)T3(26) | NA | Negative (59)Positive (19)Unknown (29) | NA | 83.6/72.2 | NA | 45.4 (17.3-73.5) | |

| Carta (2018) 28 | Retrospective cohort study | 261(248) | 64.6 (29-90) | Glottic (n = 261) | Tis (24)T1a (150)T1b (46)T2(41) | I (21)II (62)III (64)IV (18)V (94)VI (2) | Negative (251)Positive (10) | 95.1/60 | 91.9/100 | 85/87.5 | 51.6 (2-204) | |

| Chang (2017) 29 | Retrospective cohort study | 93(90) | 63 (34-89) | Glottic (n = 93) | Tis (18)T1a (32)T1b (6)T2(20)T3(17) | I (18)II (31)III (20)IV (3)V (15)VI (6) | Negative (79)Positive (14) | 92/56 | NA | NA | 35 (8-100) | |

| Day (2017) 30 | Retrospective cohort study | 90 (NA) | 63.6 (NA) | Glottic (n = 90) | Tis (5)T1(52)T2(17)T3(12)T4(4) | NA | Negative (77)Positive (4)Unknown (9) | 88/50 | NA | NA | 44.6 (8-179) | |

| Djukic (2019) 31 | Retrospective cohort study | 234(219) | 60.2 (NA) | NA | Tis (13)T1a (101)T1b (9)T2(111) | II (12)III (45)IV (48)V (119)VI (10) | Negative (182)Positive (52) | NA | 88.4/86.5 | 94.5/88.5 | NA | |

| Dyckhoff (2021) 32 | Retrospective cohort study | 96(81) | 59.6 (37-79) | Supraglottic (n = 96) | T1(31)T2(39)T3(16)T4(10) | NA | Negative (39)Positive (22)Unknown (35) | NA | NA | NA | 100.8 (0.4-201.6) | |

| Fang (2013) 33 | Retrospective cohort study | 74(71) | 66 (40-86) | Glottic (n = 75) | T1a (34)T1b (11)T2(30) | II (1)III (47)IV (3)V (17)VI (7) | Negative (32)Positive (28)Close (10)Unknown (5) | NA | NA | 85/69 | 33 (4-90) | |

| Fiz (2017) 6 | Retrospective cohort study | 634(560) | 64.1 (30-88) | Glottic (n = 634) | Tis (102)T1a (316)T1b (89)T2(127) | I (48)II (275)III (122)IV (40)V (141)VI (8) | Negative (231)Positive (288)Close (114) | NA | 88.2/73.3 | NA | 60 (12-176) | |

| Hartl (2007) 34 | Retrospective cohort study | 79(73) | 63 (34-81) | Glottic (n = 79) | Tis (21)T1a (51)T1b (7) | I (19)II (24)III (21)IV (5)V (10) | Negative (54)Positive (5)Close (20) | 91/60 | 92/100 | NA | 56 (24-150) | |

| Hendriksma (2018) 10 | Retrospective cohort study | 84(75) | 68.7 (NA) | Glottic (n = 84) | Tis (19)T1a (45)T1b (5)T2(15) | NA | Negative (16)Positive (68) | 85.9/76.9 | NA | NA | 53 (NA) | |

| Hoffmann (2016) 35 | Retrospective cohort study | 201(171) | 63 (18.2-95) | Glottic (n = 201) | NA | I (43)II (26)III (48)IV (9)V (62)VI (13) | Negative (118)Positive (83) | 87.8/85.7 | 73.2/68 | 84.4/85.2 | 50.8 (24-77.6) | |

| Jumaily (2019) 36 | Retrospective cohort study | 747(653) | 66 (21-90) | Glottic (n = 747) | T1(647)T2(100) | NA | Negative (598)Positive (149) | NA | NA | 82.9/80 | 48 (1.2-133) | |

| Lee (2013) 37 | Retrospective cohort study | 118(116) | 61.3 (31-83) | Glottic (n = 118) | T1a (88)T1b (19)T2(11) | I (10)II (18)III (49)IV (1)V (38)VI (2) | Negative (65)Positive (43)Unknown (10) | 93.1/97.7 | 89.9/84.8 | NA | 69.3 (4-175) | |

| Lucioni (2012) 38 | Retrospective cohort study | 130(126) | 73.3 (NA) | Glottic (n = 130) | Tis (11)T1a (80)T1b (27)T2(11)T3(1) | I (10)II (25)III (44)IV (20)V (26)VI (3) | Negative (77)Positive (26)Close (6)Unknown (10) | NA | NA | NA | 54.9 (33-76) | |

| Mariani (2023) 39 | Retrospective cohort study | 351(328) | 65.6 (29-90) | Glottic (n = 351) | Tis (34)T1a (193)T1b (61)T2(63) | I (34)II (94)III (77)IV (21)V (122)VI (3) | Negative (286)Positive (42)Close (23) | 94.6/57.5 | 93.2/80.9 | NA | 59.6 (NA) | |

| Michel (2011) 16 | Retrospective cohort study | 64(58) | 61 (39-88) | Glottic (n = 64) | T1a (64) | NA | Negative (40)Positive (24) | NA | 97.1/95 | 95/100 | 40 (6-149) | |

| Osuch-Wójcikiewicz (2019) 8 | Retrospective cohort study | 102(84) | 62.2 (39-88) | Glottic (n = 102) | T1a (74)T1b (15)T2(13) | II (11)III (51)IV (8)V (27)VI (5) | Negative (72)Positive (30) | NA | 75.6/72.7 | NA | 48 (30-60) | |

| Pedregal-Mallo (2018) 40 | Retrospective cohort study | 203(195) | 63 (39-86) | Supraglottic (n = 79)Glottic (n = 124) | T1(134)T2(40)T3(29) | NA | Negative (180)Positive (15)Unknown (8) | NA | NA | NA | NA | |

| Peretti (2004) 41 | Retrospective cohort study | 322(304) | 61 (29-88) | Glottic (n = 322) | Tis (37)T1a (191)T1b (55)T2(39) | I (22)II (62)III (90)IV (53)V (95) | Negative (174)Positive (148) | 88.7/93.3 | NA | NA | 77 (6-180) | |

| Rodrigo (2019) 42 | Retrospective cohort study | 72(69) | 76 (70-89) | Glottic (n = 72) | T1(63)T2(9) | I (6)II (17)III (18)IV (4)V (27) | Negative (67)Positive (5) | 79/40 | NA | NA | 65.9 (27.6-104.2) | |

| Saraniti (2022) 43 | Retrospective cohort study | 153(144) | 64 (39-82) | Glottic (n = 153) | Tis (48)T1a (48)T1b (12)T2(45) | II (96)III (6)IV (18)V (27)VI (6) | Negative (36)Positive (28)Close (43)Unknown (46) | 97.2/90.5 | 97.2/90.5 | 100/100 | 75 (60-156) | |

| Shoffel-Havaluk (2016) 44 | Retrospective cohort study | 64(63) | 64 (NA) | Glottic (n = 64) | Tis (3)T1(52)T2(9) | I (47)II (6)III (5)IV (5)V (1) | Negative (39)Positive (25) | 45.7/19.8 | NA | NA | 35.8 (21.4-50.2) | |

| Vilaseca (2021) 45 | Retrospective cohort study | 202(182) | 63.5 (20-95) | Supraglottic (n = 108)Glottic (n = 94) | T3(176)T4(26) | NA | Negative (185)Positive (17) | 70.3/47.1 | NA | 64.3/57.4 | 67.2 (1-230) | |

| *one positive margin; §more than one positive margin; LC: local control; DFS: disease-free survival; OS: overall survival; R0: negative margins; R+: positive margins; FU: follow-up; NA: not available. | ||||||||||||

| First author (year) | Inclusion and exclusion criteria | Prospective/retrospective | Patient characteristics | Tumour characteristics | Margin status definition | Endpoint | Follow-up period | Patients unavailable for statistical analysis | Quality scale |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ahmadi (2023) 24 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 7 |

| Aluffi Valletti (2018) 25 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 7 |

| Ansarin (2017) 26 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 7 |

| Blanch (2011) 27 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 7 |

| Carta (2018) 28 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 6 |

| Chang (2017) 29 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 6 |

| Day (2017) 30 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 7 |

| Djukic (2019) 31 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 7 |

| Dyckhoff (2021) 32 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 6 |

| Fang (2013) 33 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 6 |

| Fiz (2017) 6 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 7 |

| Hartl (2007) 34 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 7 |

| Hendriksma (2018) 10 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 7 |

| Hoffmann (2016) 35 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 7 |

| Jumaily (2019) 36 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 7 |

| Lee (2013) 37 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 7 |

| Lucioni (2012) 38 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 7 |

| Mariani (2023) 39 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 7 |

| Michel (2011) 16 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 7 |

| Osuch-Wójcikiewicz (2019) 8 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 7 |

| Pedregal-Mallo (2018) 40 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 6 |

| Peretti (2004) 41 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 6 |

| Rodrigo (2019) 42 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 6 |

| Saraniti (2022) 43 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 7 |

| Shoffel-Havaluk (2016) 44 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 6 |

| Vilaseca (2021) 45 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 7 |

References

- Steiner W. Experience in endoscopic laser surgery of malignant tumors of the upper aero-digestive tract. Adv Otorhinolaryngol. 1988;39:135-144. doi:https://doi.org/10.1159/000415662

- Steiner W. Results of curative laser microsurgery of laryngeal carcinomas. Am J Otolaryngol. 1993;14:116-121. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/0196-0709(93)90050-h

- Ambrosch P. The role of laser microsurgery in the treatment of laryngeal cancer. Curr Opin Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2007;15:82-88. doi:https://doi.org/10.1097/MOO.0b013e3280147336

- Peretti G, Piazza C, Cocco D. Transoral CO(2) laser treatment for T(is)-T(3) glottic cancer: the University of Brescia experience on 595 patients. Head Neck. 2010;32:977-983. doi:https://doi.org/10.1002/hed.21278

- Blanch J, Vilaseca I, Bernal-Sprekelsen M. Prognostic significance of surgical margins in transoral CO2 laser microsurgery for T1-T4 pharyngo-laryngeal cancers. Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol. 2007;264:1045-1051. doi:https://doi.org/10.1007/s00405-007-0320-2

- Fiz I, Mazzola F, Fiz F. Impact of close and positive margins in transoral laser microsurgery for Tis-T2 glottic cancer. Front Oncol. 2017;7. doi:https://doi.org/10.3389/fonc.2017.00245

- Meulemans J, Hauben E, Peeperkorn S. Transoral laser microsurgery (TLM) for glottic cancer: prospective assessment of a new pathology workup protocol. Front Surg. 2020;7. doi:https://doi.org/10.3389/fsurg.2020.00056

- Osuch-Wójcikiewicz E, Rzepakowska A, Sobol M. Oncological outcomes of CO2 laser cordectomies for glottic squamous cell carcinoma with respect to anterior commissure involvement and margin status. Lasers Surg Med. 2019;51:874-881. doi:https://doi.org/10.1002/lsm.23130

- Fiz I, Koelmel J, Sittel C. Nature and role of surgical margins in transoral laser microsurgery for early and intermediate glottic cancer. Curr Opin Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2018;26:78-83. doi:https://doi.org/10.1097/MOO.0000000000000446

- Hendriksma M, Montagne M, Langeveld T. Evaluation of surgical margin status in patients with early glottic cancer (Tis-T2) treated with transoral CO2 laser microsurgery, on local control. Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol. 2018;275:2333-2340. doi:https://doi.org/10.1007/s00405-018-5070-9

- Lucioni M, Bertolin A, D’Ascanio L. Margin photocoagulation in laser surgery for early glottic cancer: impact on disease local control. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2012;146:600-605. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/0194599811433270

- Ansarin M, Santoro L, Cattaneo A. Laser surgery for early glottic cancer: impact of margin status on local control and organ preservation. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2009;135:385-390. doi:https://doi.org/10.1001/archoto.2009.10

- Peretti G, Nicolai P, Redaelli De Zinis L. Endoscopic CO2 laser excision for tis, T1, and T2 glottic carcinomas: cure rate and prognostic factors. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2000;123:124-131. doi:https://doi.org/10.1067/mhn.2000.104523

- Zapater E, Hernández R, Reboll R. Pathological examination of cordectomy specimens: analysis of negative resection. Auris Nasus Larynx. 2009;36:321-325. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.anl.2008.07.007

- Jäckel M, Ambrosch P, Martin A. Impact of re-resection for inadequate margins on the prognosis of upper aerodigestive tract cancer treated by laser microsurgery. Laryngoscope. 2007;117:350-356. doi:https://doi.org/10.1097/01.mlg.0000251165.48830.89

- Michel J, Fakhry N, Duflo S. Prognostic value of the status of resection margins after endoscopic laser cordectomy for T1a glottic carcinoma. Eur Ann Otorhinolaryngol Head Neck Dis. 2011;128:297-300. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.anorl.2011.05.006

- Liberati A, Altman D, Tetzlaff J. The PRISMA statement for reporting systematic reviews and meta-analyses of studies that evaluate health care interventions: explanation and elaboration. PLoS Med. 2009;6. doi:https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pmed.1000100

- Altman D, McShane L, Sauerbrei W. Reporting recommendations for tumor marker prognostic studies (REMARK): explanation and elaboration. PLoS Med. 2012;9. doi:https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pmed.1001216

- Tierney J, Stewart L, Ghersi D. Practical methods for incorporating summary time-to-event data into meta-analysis. Trials. 2007;8. doi:https://doi.org/10.1186/1745-6215-8-16

- Cochran W. The combination of estimates from different experiments. Biometrics. 1954;10:101-129.

- Jackson D, White I, Riley R. Quantifying the impact of between-study heterogeneity in multivariate meta-analyses. Stat Med. 2012;31:3805-3820. doi:https://doi.org/10.1002/sim.5453

- Viechtbauer W, Cheung M. Outlier and influence diagnostics for meta-analysis. Res Synth Methods. 2010;1:112-125. doi:https://doi.org/10.1002/jrsm.11

- Egger M, Davey Smith G, Schneider M. Bias in meta-analysis detected by a simple, graphical test. BMJ. 1997;315:629-634. doi:https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.315.7109.629

- Ahmadi N, Stone D, Stokan M. Treatment of early glottic cancer with transoral laser microsurgery: an Australian experience. Indian J Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2023;75:661-667. doi:https://doi.org/10.1007/s12070-022-03392-8

- Aluffi Valletti P, Taranto F, Chiesa A. Impact of resection margin status on oncological outcomes after CO2 laser cordectomy. Acta Otorhinolaryngol Ital. 2018;38:24-30. doi:https://doi.org/10.14639/0392-100X-870

- Ansarin M, Cattaneo A, De Benedetto L. Retrospective analysis of factors influencing oncologic outcome in 590 patients with early-intermediate glottic cancer treated by transoral laser microsurgery. Head Neck. 2017;39:71-81. doi:https://doi.org/10.1002/hed.24534

- Blanch J, Vilaseca I, Caballero M. Outcome of transoral laser microsurgery for T2-T3 tumors growing in the laryngeal anterior commissure. Head Neck. 2011;33:1252-1259. doi:https://doi.org/10.1002/hed.21605

- Carta F, Bandino F, Olla A. Prognostic value of age, subglottic, and anterior commissure involvement for early glottic carcinoma treated with CO2 laser transoral microsurgery: a retrospective, single-center cohort study of 261 patients. Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol. 2018;275:1199-1210. doi:https://doi.org/10.1007/s00405-018-4890-y

- Chang C, Chu P. Predictors of local recurrence of glottic cancer in patients after transoral laser microsurgery. J Chin Med Assoc. 2017;80:452-457. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jcma.2017.04.002

- Day A, Sinha P, Nussenbaum B. Management of primary T1-T4 glottic squamous cell carcinoma by transoral laser microsurgery. Laryngoscope. 2017;127:597-604. doi:https://doi.org/10.1002/lary.26207

- Djukic V, Milovanović J, Jotić A. Laser transoral microsurgery in treatment of early laryngeal carcinoma. Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol. 2019;276:1747-1755. doi:https://doi.org/10.1007/s00405-019-05453-1

- Dyckhoff G, Warta R, Herold-Mende C. An observational cohort study on 194 supraglottic cancer patients: implications for laser surgery and adjuvant treatment. Cancers (Basel). 2021;13. doi:https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers13030568

- Fang T, Courey M, Liao C. Frozen margin analysis as a prognosis predictor in early glottic cancer by laser cordectomy. Laryngoscope. 2013;123:1490-1495. doi:https://doi.org/10.1002/lary.23875

- Hartl D, de Monès E, Hans S. Treatment of early-stage glottic cancer by transoral laser resection. Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol. 2007;116:832-836. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/000348940711601107

- Hoffmann C, Hans S, Sadoughi B. Identifying outcome predictors of transoral laser cordectomy for early glottic cancer. Head Neck. 2016;38:E406-E411. doi:https://doi.org/10.1002/hed.24007

- Jumaily M, Faraji F, Osazuwa-Peters N. Prognostic significance of surgical margins after transoral laser microsurgery for early-stage glottic squamous cell carcinoma. Oral Oncol. 2019;97:105-111. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.oraloncology.2019.08.005

- Lee H, Chun B, Kim S. Transoral laser microsurgery for early glottic cancer as one-stage single-modality therapy. Laryngoscope. 2013;123:2670-2674. doi:https://doi.org/10.1002/lary.24080

- Lucioni M, Bertolin A, Rizzotto G. CO(2) laser surgery in elderly patients with glottic carcinoma: univariate and multivariate analyses of results. Head Neck. 2012;34:1804-1809. doi:https://doi.org/10.1002/hed.22907

- Mariani C, Carta F, Bontempi M. Management and oncologic outcomes of close and positive margins after transoral CO2 laser microsurgery for early glottic carcinoma. Cancers (Basel). 2023;15. doi:https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers15051490

- Pedregal-Mallo D, Sánchez Canteli M, López F. Oncological and functional outcomes of transoral laser surgery for laryngeal carcinoma. Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol. 2018;275:2071-2077. doi:https://doi.org/10.1007/s00405-018-5027-z

- Peretti G, Piazza C, Bolzoni A. Analysis of recurrences in 322 Tis, T1, or T2 glottic carcinomas treated by carbon dioxide laser. Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol. 2004;113:853-858. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/000348940411301101

- Rodrigo J, García-Velasco F, Ambrosch P. Transoral laser microsurgery for glottic cancer in the elderly: efficacy and safety. Head Neck. 2019;41:1816-1823. doi:https://doi.org/10.1002/hed.25616

- Saraniti C, Montana F, Chianetta E. Impact of resection margin status and revision transoral laser microsurgery in early glottic cancer: analysis of organ preservation and local disease control on a cohort of 153 patients. Braz J Otorhinolaryngol. 2022;88:669-674. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bjorl.2020.09.008

- Shoffel-Havakuk H, Lahav Y, Davidi E. The role of separate margins sampling in endoscopic laser surgery for early glottic cancer. Acta Otolaryngol. 2016;136:491-496. doi:https://doi.org/10.3109/00016489.2015.1132843

- Vilaseca I, Aviles-Jurado F, Valduvieco I. Transoral laser microsurgery in locally advanced laryngeal cancer: prognostic impact of anterior versus posterior compartments. Head Neck. 2021;43:3832-3842. doi:https://doi.org/10.1002/hed.26878

- Mannelli G, Meccariello G, Deganello A. Impact of low-thermal-injury devices on margin status in laryngeal cancer. An experimental ex vivo study. Oral Oncol. 2014;50:32-39. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.oraloncology.2013.10.001

- Verro B, Greco G, Chianetta E. Management of early glottic cancer treated by CO2 laser according to surgical-margin status: a systematic review of the literature. Int Arch Otorhinolaryngol. 2021;25:E301-E308. doi:https://doi.org/10.1055/s-0040-1713922

- Mariani C, Carta F, Tatti M. Shrinkage of specimens after CO2 laser cordectomy: an objective intraoperative evaluation. Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol. 2021;278:1515-1521. doi:https://doi.org/10.1007/s00405-021-06625-8

- Brøndbo K, Fridrich K, Boysen M. Laser surgery of T1a glottic carcinomas; significance of resection margins. Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol. 2007;264:627-630. doi:https://doi.org/10.1007/s00405-006-0233-5

- Buchanan M, Coleman H, Daley J. Relationship between CO2 laser-induced artifact and glottic cancer surgical margins at variable power doses. Head Neck. 2016;38:E712-E716. doi:https://doi.org/10.1002/hed.24076

- Charbonnier Q, Thisse A, Sleghem L. Oncologic outcomes of patients with positive margins after laser cordectomy for T1 and T2 glottic squamous cell carcinoma. Head Neck. 2016;38:1804-1809. doi:https://doi.org/10.1002/hed.24518

- Hans S, Crevier-Buchman L, Circiu M. Oncological and surgical outcomes of patients treated by transoral CO2 laser cordectomy for early-stage glottic squamous cell carcinoma: a retrospective chart review. Ear Nose Throat J. 2021;100:33S-37S. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/0145561320911486

- Simo R, Bradley P, Chevalier D. European Laryngological Society: ELS recommendations for the follow-up of patients treated for laryngeal cancer. Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol. 2014;271:2469-2479. doi:https://doi.org/10.1007/s00405-014-2966-x

- Remacle M, Matar N, Delos M. Is frozen section reliable in transoral CO(2) laser-assisted cordectomies?. Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol. 2010;267:397-400. doi:https://doi.org/10.1007/s00405-009-1101-x

- Vander Poorten V, Meulemans J, Van Lierde C. Current indications for adjuvant treatment following transoral laser microsurgery of early and intermediate laryngeal cancer. Curr Opin Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2021;29:79-85. doi:https://doi.org/10.1097/MOO.0000000000000702

- Preuss S, Cramer K, Drebber U. Second-look microlaryngoscopy to detect residual carcinoma in patients after laser surgery for T1 and T2 laryngeal cancer. Acta Otolaryngol. 2009;129:881-885. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/00016480802441739

- Hanna J, Brauer P, Morse E. Margins in laryngeal squamous cell carcinoma treated with transoral laser microsurgery: a National Database study. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2019;161:986-992. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/0194599819874315

- Marchi F, Piazza C, Ravanelli M. Role of imaging in the follow-up of T2-T3 glottic cancer treated by transoral laser microsurgery. Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol. 2017;274:3679-3686. doi:https://doi.org/10.1007/s00405-017-4642-4

- Piazza C, Cocco D, De Benedetto L. Narrow band imaging and high definition television in the assessment of laryngeal cancer: a prospective study on 279 patients. Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol. 2010;267:409-414. doi:https://doi.org/10.1007/s00405-009-1121-6

- Remacle M, Eckel H, Antonelli A. Endoscopic cordectomy. A proposal for a classification by the Working Committee, European Laryngological Society. Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol. 2000;257:227-231. doi:https://doi.org/10.1007/s004050050228

- Brook I. Early side effects of radiation treatment for head and neck cancer. Cancer Radiother. 2021;25:507-513. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.canrad.2021.02.001

- Gessert T, Britt C, Maas A. Chondroradionecrosis of the larynx: 24-year University of Wisconsin experience. Head Neck. 2017;39:1189-1194. doi:https://doi.org/10.1002/hed.24749

Downloads

License

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

Copyright

Copyright (c) 2025 Società Italiana di Otorinolaringoiatria e chirurgia cervico facciale

How to Cite

- Abstract viewed - 1037 times

- PDF downloaded - 348 times