Head and neck

Vol. 45: Issue 3 - June 2025

Microsurgery in primary tumours of the parapharyngeal space: observational retrospective analysis of a series of consecutive cases

Abstract

Objective. To investigate safety and efficacy of the microsurgical approach to parapharyngeal space (PPS) tumour. A secondary goal was to evaluate the correspondence between preoperative and final histopathologic diagnosis after surgery.

Methods. A consecutive series of primary PPS tumours treated between 1985 and 2022 in 2 tertiary referral centres with a microsurgical cervico-parotid approach was considered. The sample included 97 tumours (88 benign and 9 malignant) in 94 patients, of which 11 affected by recurrent tumours when first diagnosed at our centres. The surgical approaches, planned on the presumptive preoperative diagnosis, were pericapsular and en bloc resections (including either conservative or radical resections of the PPS).

Results. Pericapsular and en bloc resections of the PPS achieved complete removal in 88 out of 97 tumours. Relapses after PPS microsurgery occurred only in 8 cases (4 pleomorphic adenomas, 2 malignant schwannomas, one melanoma, and one haemangiopericytoma). Four of the 8 relapsed cases were recurrent cases when first seen at our centres. A complete correspondence between preoperative diagnosis and final histology occurred only in the group of benign lesions classified as paraganglioma, schwannoma, or lipoma, submitted to pericapsular resection.

Conclusions. Microsurgery may support the transcervical-parotid approach, by enhancing the operative space through narrow surgical corridors, improving dissection on critical cleavage planes, vessels and nerves, and allowing the exposure of both caudal and cranial extent of the lesions. In our series, pericapsular and en bloc resections of the PPS were effective in most of the included patients. In high-grade malignancies, where the morbidity of a wider resection beyond the PPS walls may include vessels and nerves, the indication should be accurately balanced.

Introduction

The parapharyngeal space (PPS) is a visceral virtual space bounded by the cranial base, pharynx, cervical spine and masticatory space. Its walls are represented by the tissues of adjacent organs, which make up its medial, lateral, anterior, posterior and superior walls 1-6. It contains fat and loose connective tissue, lymph nodes, the parapharyngeal portion of the parotid gland, minor salivary glands, muscles, cranial nerves IX to XII, sympathetic chain, carotid arteries and jugular vein. A diffuse, although not universally accepted, conception divides the PPS into a pre- and post-styloid compartments 2,6. The pre-styloid PPS extends from the spheno-petrous skull base to the greater horn of the hyoid bone, resembling a three-sided pyramid rooted at the skull, with the apex on the hyoid. The post-styloid PPS is the four-sided carotid space, extending from the skull base to the aortic arch 7. Tumours may originate either primarily from the parapharyngeal space or from the deep lobe of the parotid gland and are conventionally included in the group of PPS tumours. The most common tumours arising from the pre-styloid compartment are deep lobe parotid neoplasms, as well as minor salivary glands tumours. Instead, in the post-styloid compartment, schwannomas and paragangliomas are the most frequently encountered. A high percentage of less frequent and rare tumours originate in the PPS from fat, connective tissue, and lymphatic nodes. Preoperative diagnosis is obtained with imaging and relies heavily on the radiological features and fine needle aspiration cytology (FNAC) 8-10. However, for a number of tumours, the precise nature is undefined or, more importantly, a missing diagnosis in the preoperative setting is not uncommon at the time of surgery 7,11. Core needle biopsy was recently added to preoperative investigations. In addition to the rarity of these tumours, the large variability of pathological entities and the difficulty of surgical access make the approach to diseases of the PPS intrinsically difficult 7,12.

This points to the need to define clear principles for the management of these lesions. Since incorrect preoperative diagnosis still occurs 6,10,12, an oncologically sound protocol is advocated to prevent potential worsening of prognosis. As a result, in our clinical practice, we assume that resection of PPS lesions should be based on the presumptive preoperative diagnosis and include an adequate safety margin to account for possible preoperative misdiagnoses. To achieve this, we employ accurate preoperative planning combined with a well-defined type of microsurgical resection. Procedures were performed according to the principles and skills of skull base microsurgery. The aim of this study was to investigate safety and efficacy of the microsurgical approach to primary PPS tumours, assessing the outcomes of different types of resections, as indicated by the presumptive preoperative diagnosis. A secondary goal was to evaluate the correspondence between preoperative diagnosis and the surgical procedure applied.

Materials and methods

Patients

This study was conducted in accordance with the principles of the Helsinki Declaration. All patients signed an informed consent form regarding the processing and publication of their data, which were examined in agreement with the Italian privacy and sensitive data laws, and institutional regulations. A series of consecutive patients, diagnosed as having primary PPS tumours, were retrieved and retrospectively analysed for this study. All patients had been operated on between 1985 and 2022 by the same surgeons (AM, EZ) in 2 tertiary referral centres (Hospital of Bergamo and University Hospital of Padua, Italy) using a microsurgical transcervical-parotid approach. Radiological investigation was the main tool for diagnosis 11,13-15. CT and digital angiography (DA) had been used in the period between 1985 and 1990. Since 1990, MRI has been the principal investigation for all PPS tumours, with occasional use of angio-CT/MRI. Transcutaneous FNAC was used in cases with doubtful diagnosis. For all patients enrolled, clinical, surgical and radiological data were obtained. Postoperative radiation was indicated in case of high-grade or recurrent malignant tumours, involved margins at histopathological examination and extracapsular nodal extension. Follow-up was based on regular clinical examination and imaging by multi-parametric MRI and/or CT, with a scheduled timing depending on definitive histopathological diagnosis. For patients with benign disease, imaging was performed after 1, 3, 5, and 10 years. Patients with malignant disease were followed for the first time at 6 months after surgery, then every year for the first 5 years and subsequently at 7 and 10 years, along with chest X-rays. The mean follow-up period was 7 years (range, 1.5-14).

Surgical technique

GENERAL PRINCIPLES

The microsurgical approach to the PPS was not based on the classical division into pre- and post-styloid compartments. Rather it provided surgical access as much as was required to achieve the planned resection, which might range from a pericapsular resection to a complete PPS resection. Resection might also enlarge beyond its boundaries, including the spheno-petrous-occipital skull base and, possibly, the spaces lying beyond the anterior, posterior and medial walls. A detailed description of PPS surgical anatomy is beyond the goals of this work. However, a few notes on anatomical landmarks of the surgical route must be underlined. The lateral access to the PPS is confined between the mandibular ramus, tympano-mastoid bone and lateral process of C1. As a general concept, the combination of a convenient angle of view, anterior retraction of the mandible as obtained with an autostatic retractor applied to the mandible and mastoid process, as well as of opposite structures, provides the corridors for surgery. Microsurgical manoeuvres reach the deepest aspect of the PPS despite a narrow corridor. For most of these procedures a certain degree of parotid mobilisation or removal is required, depending on size, preoperative diagnosis, and planned resection extent. This involves up-folding of the parotid lower pole onto the mandibular branch of the facial nerve, or removal of one parotid lobe, or even total parotidectomy. Our microsurgical approach involved different handling of PPS content, according to the presumptive preoperative diagnosis and included 3 different types of resections of increasing extent:

- Pericapsular resection (PCR), dissecting exclusively along the tumour capsule;

- Conservative resection (CR), extending along the walls of the PPS, removing the tumour along with the contents of the PPS (loose fat tissue, lymph nodes, salivary glands tissue, muscles), but preserving the internal carotid artery, jugular vein and cranial nerves IX to XII. In this procedure, the planes of resection followed the PPS walls, aiming to achieve a safe tissue margin around the tumour;

- Radical resection (RR), implying the same boundaries as CR, but also including the carotid arteries, jugular vein and/or cranial nerves in the resection block. When tumours extended to the walls of the PPS, CR and PCR could have similar planes as there was an overlapping between the two procedures. Resecting beyond the walls of the PPS was contemplated but not performed.

COMMON STEPS OF PPS RESECTIONS

After general endotracheal anaesthesia, the patient was placed in a supine position with the head turned 30° to the opposite side. Intraoperative free-run electromyography (EMG) electrodes were placed to monitor cranial nerves VII and X. The skin incision was preauricular-upper cervical. The skin-platysma flap was raised to expose the parotid, mastoid process, sternocleidomastoid muscle, submandibular gland and hyoid bone, along with the digastric muscle. The microscope with a 250 mm front lens was positioned. The basic microsurgical instruments were a Freer-type elevator with semi-sharp ends (one straight, the other curved), suction-irrigation tubes, bipolar coagulation forceps and scissors. The parotid gland was mobilised at its inferior and posterior margins. The facial nerve was identified and dissected up to its third divisions, if necessary. The mandibular branch could be protected with the upfolded lower pole of the parotid. The jugular vein and carotid arteries were identified at the lower limit of the field. When the skull base was part of the approach, bony landmarks on the petro-sphenoid plane were useful to advance across the base. They were anteromedially aligned from the mastoid process to styloid process, sphenoid spine, foramen spinosum, foramen ovale, and pterigoid process. This mastoid-pterigoid line showed the direction and depth for the advancing dissection. The PCR involved isolating the tumour from the surrounding tissues, taking care to preserve the capsule surface. The mid-cervical fascia might involve the tumour and could be followed along the neurovascular axis. Depending on tumour size, the styloid bundle and spino-mandibular ligament could be rescinded. In the conservative and radical resections (CR and RR) of the PPS, dissection was carried out along the walls of the PPS. The posterior aspect was the lateral process of C1 and the vertebro-basilar fascia, the superior aspect was the spheno-temporal bone plate, the anterior aspect was the mandibular ramus and medial pterygoid muscle, the medial was the pharyngeal aponeurosis and palatine muscles. The access to surgical corridors was opened up by anterior retraction of the mandible and pterygoid muscle, sectioning the styloid muscles and stylo-mandibular ligament, drilling flat the styloid process and mobilising the parotid at the inferior and posterior margin. Further access might be added by mastoidectomy and exposure of the vertical Fallopian canal, making the intra-temporal facial nerve in continuity with its extra-temporal trunk, and by exposure of the cranial base at the spheno-temporal suture at the level of the sphenoid spine and entry of carotid canal and jugular vein. The resections of PPS began at the lower pole of the PPS by raising the fibro-fatty tissues away from the pharynx and prevertebral plane, thereby exposing the major vessels. Posterior dissection started at the tip of the lateral process of C1 and proceeded medially along the plane of the vertebro-basilar fascia. The styloid muscles were cut, and the styloid process removed, as it obstructed the access to the PPS, and its base was drilled flat. This opened the way for medial dissection to the skull base, which was usually possible from below the facial nerve, but occasionally above the main trunk. The jugular vein, which could be either sacrificed or maintained, together with the internal carotid artery defined the posterior plane of the resection, their vascular fascia being preserved or opened according to the pathology. Cranial nerves IX to XII were preserved. The ramus of the mandible had to be displaced forwards to gain adequate access to the anterior and medial dissection. A strong hook or self-retaining retractor attached to the posterior margin of the mandible and tympanic bone was necessary. As a result of such traction, the tendinous part of the medial pterygoid muscle was exposed. The dissection followed the surface of the pterygoid muscles and reached the lateral pterygoid plate with its hamulus and the pharyngeal wall. The plate felt like a hard ridge bulging out of the depressible pterygoid muscle. The lateral pterygoid muscle was found on the uppermost part of the dissection. Cutting the styloid bundle allowed additional exposure. Dissection of the cranial side of the specimen started at the drill-flattened root of the styloid process. Then, the spheno-petrous bony surface was exposed in a superomedial direction to the spine of the sphenoid. RR extended to the posterior wall of the PPS, including the jugular vein, internal carotid artery and, if indicated, cranial nerves. On completion, the jugular fossa had to be packed firmly from below with reabsorbable oxidised cellulose.

SURGICAL PROTOCOL

The procedure planning (PCR, CR, RR) was defined according to the following protocol:

- First diagnosis of paragangliomas, schwannomas and lipomas were planned to be removed by PCR;

- Recurrent tumours and first diagnosis of all the other clinico-radiological entities were planned to be resected with CR;

- RR was reserved for malignancies extending to the neurovascular axis.

This protocol was based on the assumption that for paragangliomas, schwannomas and lipomas the clinico-radiological diagnosis was most likely to be correct, and that a complete and satisfactory resection could be achieved with PCR. The preoperative diagnosis of all other lesions including other benign tumours, pleomorphic adenomas and malignant tumours, was not considered as safe as to permit a PCR and were all submitted to CR. In particular, the uncertainty regarding preoperative diagnosis of rare benign tumours made the choice of a CR more appropriate. The pleomorphic adenoma (PA) was managed with CR and parotidectomy assuming that this would minimise tumour spilling and seeding 17. Postoperative radiotherapy was administered in 3 cases: one malignant schwannoma, one carcinoma ex-PA, and one sarcoma. Moreover, in 3 recurrent cases (one carcinoma ex-PA, one malignant peripheral sheath tumour, and one haemangiopericytoma), radiotherapy had been administered after the first surgery, before our evaluation.

Statistical analysis

Continuous variables were summarised with median and range, while categorical ones were described in terms of count and percentage in each category. Fisher’s exact test was employed to investigate differences in the distribution of categorical variables across groups. For all analyses, p value < 0.05 was considered indicative of statistical significance. The STATA 16.0 IC statistical package (Stata Corp LP, College Station, TX, USA) was used for all analyses.

Results

General clinical features

Ninety-four consecutive patients with primary parapharyngeal tumours (50 females and 44 males; median age, 41 years; range, 21-77), accounting for 97 surgical procedures (including 3 bilateral cases of carotid paragangliomas) were considered in this retrospective study. The median follow-up was 7 years (range, 1.5-14). A detailed breakdown of the diagnoses is reported in Table I.

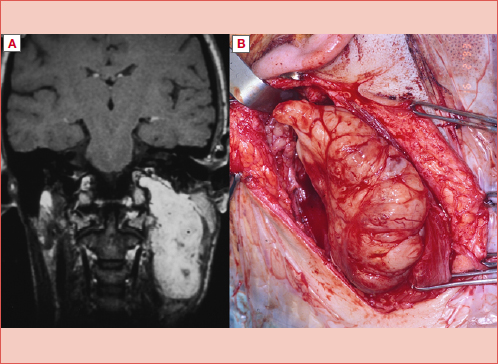

Eighty-eight tumours were benign (Figs. 1-3, and Cover figure), while 9 were malignant (Figs. 4-6). Eighty-six were first-diagnosis tumours, while 11 were recurrences after previous treatment (Tab. I) and included 3 benign (PA) and 8 malignant tumours (1 sarcoma, 2 malignant peripheral sheath tumours, 2 carcinoma ex-PA, one rhabdomyosarcoma, one haemangiopericytoma, and one lymphoma). Mean tumour size was 5.5 cm (range, 2.5-12). Overall, 9 of the 97 cases (9%) had an incorrect preoperative diagnosis (Tab. II). Of note, 3 PAs at clinical preoperative diagnosis showed carcinoma ex-PA at pathology in 2 cases and melanoma in one case. In the group of 67 cases of paragangliomas, schwannomas and lipomas, only one case (1.4%) was misclassified preoperatively (teratoma instead of lipoma). The remaining 30 cases included 8 (26.6%) preoperatively misdiagnosed cases, of which 5 (62.5%) were malignancies instead of preoperatively diagnosed benign tumours. The difference in terms of distribution of preoperative misdiagnoses was significantly lower for the paraganglioma/schwannoma/lipoma group compared to the other cases (Fisher’s exact test, p < 0.001), making these patients as those with the highest preoperative diagnostic certainty.

Surgical procedures

The microsurgical cervico-parotid approach was performed with PCR in 68 cases, CR in 28 patients, and RR in one case. There were only 2 exceptions to the protocol, a patient with a myoepithelioma that was managed by a PCR instead of a CR as the protocol would have required, and a lipoma, which was removed by CR instead of PCR, because of a preoperative misdiagnosis (suspected teratoma due to the presence of calcifications within the tumour at preoperative radiology). Further surgical steps were added in few cases. In one patient with recurrent low-grade malignant schwannoma, a lateral mandibulotomy was added to CR to enhance exposure. Trans-mastoid exposure of the facial nerve was performed in 2 cases of recurrent PA. In 4 patients with vagal paragangliomas, the cervico-parotid PCR approach was combined with an infratemporal type A approach, directed to synchronous tympano-jugular paragangliomas. Total parotidectomy was performed in 15 patients with preoperative diagnosis of PPS PA. The deep lobe was selectively removed in one patient with a low-grade malignant schwannoma to improve exposure. In 32 cases, only the inferior pole of the parotid required mobilisation.

Outcomes

In our case series, the rate of misdiagnosed cases (postoperative vs preoperative diagnosis) was as follows:

- 9 of the overall 97 tumours (9%);

- 5 of the 86 (5.8%) first diagnosis tumours (lipoma, myoepithelioma, melanoma, malignant schwannoma, post-CRT lymphadenitis);

- 4 of the 11 (36%) cases which were already recurrences when first seen at our centres, all malignant (one hemangiopericytoma, one low-grade malignant schwannoma, and 2 carcinoma ex-PA).

In particular, we therefore distinguished a:

- “Safe” diagnosis group: one misdiagnosed case (mistake of teratoma vs lipoma) out of 67 tumours (1.5%);

- “Unsafe” diagnosis group: 8 misdiagnosed cases out of 30 tumours (26.7%) (Tab. II) of which 5 were malignant lesions (16.7%);

- 5 malignant cases in the overall group of 9 misdiagnosed tumours (55.6%) (Tab. II).

Regarding oncologic outcomes:

- overall rate of postoperative relapse: 8/97 cases (8.2%);

- rate of postoperative relapses in the “safe” diagnosis group: 0/67 cases (0%);

- rate of postoperative relapses in the “unsafe” diagnosis group: 8/30 cases (30%);

- rate of postoperative relapses in the first-diagnosis cases: 4/86 (4.7%) (2 PA, one melanoma, and one malignant schwannoma);

- rate of postoperative relapses in the recurrent cases: 4/11 (36.4%) (2 PA, one malignant schwannoma, and one hemangiopericytoma).

In detail, in the first-diagnosis group (86 patients), there were 4 cases (4.6%) showing local relapse (two PA, one malignant schwannoma, and one melanoma); in the latter 2 cases, an incorrect preoperative diagnosis of neurofibroma and pleomorphic neurofibroma had been made.

In the recurrent tumours group (11 cases of which 3 PA, 2 carcinomas ex-PA, 2 malignant schwannomas, one lymphoma, one sarcoma, one hemangiopericytoma, and one rhabdomyosarcoma), 4 patients (36.4%) presented further local relapse (2 PA, one malignant schwannoma, and one haemangiopericytoma).

Our postoperative relapse rate was significantly higher for patients who had previously experienced a recurrence compared with the first-diagnosis cases (Fisher’s exact test, p = 0.001).

Considering the rate of relapse by surgery type, no patient who underwent PCR experienced disease relapse, while the 8 relapses were all distributed within the CR group. Such differences in the recurrence rate across various treatment groups were statistically significant (Fisher’s exact test, p < 0.001).

Overall, among the 8 cases who experienced postoperative local relapse, 4 belonged to the group of PA (4/17, 23.5%), and 4 (50%) to the group of malignancies (2 malignant schwannomas, one melanoma, and one hemangiopericytoma). No recurrence was noticed for other disease categories. The recurrence rate was significantly higher for patients with malignant tumours compared to the other diagnoses (Fisher’s exact test, p < 0.001).

The most severe postoperative complication was an internal carotid artery thrombosis, which occurred in a vagal paraganglioma excised with PCR, resulting in a hemiparesis that recovered incompletely. In 4 of the 23 cases of vagal PGL, a preoperative vagal dysfunction had already been present, while in 19 function and anatomical continuity of vagal nerve could not be preserved at surgery. Three patients also lost glossopharyngeal or hypoglossal nerve function. Four patients (presenting with both jugular and vagal paragangliomas), treated with a combined PCR – infratemporal type A approach, had loss of function of cranial nerves IX to XI due to jugular paragangliomas. Among carotid paragangliomas, in 20 cases of Shamblin 2-3, loss of the secondary branches of cranial nerves X and XII occurred, i.e. the external branch of the superior laryngeal nerve of the vagal and the descending branch of the hypoglossal nerve. The cases of benign schwannoma lost the nerve from which the tumour originated, i.e. cranial nerve X in 8 patients, IX in one, and XII in another. The case of malignant schwannoma also lost cranial nerve X, and the patient with recurrent low-grade malignant schwannoma lost cranial nerves from VII to XII. Cranial nerves IX to XI were also lost in a RR performed for a presumed recurrent nodal metastasis of nasopharyngeal carcinoma.

Discussion

The aim of our work was to assess the role of an oncologically-sound protocol, combining the transparotid-transcervical approach with microsurgery, to ascertain the appropriateness of the resection and related outcomes with reference to the preoperative diagnosis and definitive pathology. The high rate (90.8%) of diagnostic accuracy reported in our series might be misleading, since it derived from a mix of a “safe” group with a benign diagnosis (paragangliomas, schwannomas, and lipomas) with nearly negligible risk of misdiagnosis, and the other histotypes which showed a higher risk of incorrect classification (Tab. II). Misdiagnosed cases represented 9.2% in our series. In details, incorrect diagnosis occurred in 26.6% of cases of the preoperative presumed “unsafe diagnosis” group and in 1.4% of the “safe diagnosis” cases (Tab. II, p < 0.001) where the mistake occurred in a benign case. These data are in line with what has been reported by others 18. The rate of malignancies diagnosed at pathology in the group of “unsafe diagnosis” was 16% and in 62.5% of the cases with incorrect preoperative diagnosis (“misdiagnosed” cases, Tab. II). The rate of uncertain preoperative diagnosis might have been reduced by a core needle biopsy, but this diagnostic technique has only become extensively available for PPS lesions in recent years 18,19 and was not frequently used in our series. The lack of core-needle biopsy data represents a weakness of our experience, although it remains unclear whether its role would have eliminated the problem of indefinite diagnosis in some PPS tumours 19. Currently, multi-parametric MRI and ultrasound-guided core needle biopsy are indicated in cases with uncertain diagnosis after clinical-radiological preoperative work-up. In the case of persistent doubtful diagnosis, en bloc resection by CR with the largest safe margins is the procedure of choice. The oncological appropriateness of the approach was assessed with reference to the outcome. Our results showed that local relapse was significantly higher in already recurrent cases and in malignant tumours, compared to the other patients (first-diagnosis cases and benign tumours, respectively). The fact that no recurrence occurred in the “safe” diagnosis group of paraganglioma/schwannoma/lipoma after PCR approach seems to support that pericapsular dissection is appropriate in patients with a preoperative diagnosis of these benign neoplasms. All the remaining cases involving other rare benign tumours or uncertain preoperative diagnosis, recurrences, and malignant tumours were treated with broader resection (CR) of the PPS. This might be theoretically considered an overtreatment for a number of benign lesions, but took into account the non-negligible risk of wrong diagnosis at pathology (Tabs. I-II) and aimed to provide an adequate approach also in this event. CR showed good oncological results even in low-grade malignancies. Conversely, the high recurrence rate in high-grade malignancies (such as melanoma and malignant schwannoma) highlighted the issue of the inadequacy of “free margins” in a malignant tumour and pointed to consider a wider approach, like an RR or a combined skull base approach 20. In PPS malignancies, surgery was constrained by the lack of safe tissue to establish free margins of resection and the presence of vital neurovascular structures. In addition, insufficient knowledge of microscopic tumour diffusion implies only conjectural information of tumour extent. Enlarging the resection to full PPS and beyond its walls, with the potential sacrifice of the jugular vein, and/or carotid, and/or cranial nerves, involved unassessed balance of morbidity versus benefit. A high-grade malignancy represents a challenge in PPS tumours and remains an unsolved problem. The few successful cases of low-grade malignancy treated with conservative resection of the parapharyngeal space did not allow to ascertain which size, site and histology require a larger resection.

With these limitations, microsurgical PCR and CR were effective in setting a rationale with preoperative diagnosis, pathology, and outcome. PA represented another point of reflection. Conversely to what is widely recommended for the parotid gland setting, where normal parotid tissue around the tumour is advocated in both extracapsular resection and parotidectomy 21, a large PA in the PPS may not have enough fat, connective and normal gland tissue around it to allow a safe extracapsular resection. Recurrence from a benign PA turning into a more severe disease is not an exceptional event 9. In the PPS, grouping together heterogeneous histotypes because of a common site of origin and growth outlines the common aspects of treatment, but disregards the typical features of each tumour. This bias was also present in our series, where only paraganglioma, PA and schwannoma allowed a strong relationship between diagnosis and appropriateness of treatment to be recognised. In view of this, our experience led us to hypothesise a comprehensive clinical approach, as reported in Figure 7.

The contribution of microsurgery was explored in our study. It promoted easier surgical handling in the deepest areas of the PPS, also allowing the skull base to be controlled across the narrow trans-cervical-parotid surgical corridor. The skull base represents the roof of the PPS, with the adjacent sites of the spheno-petrous-occipital areas being a continuum with it in terms of surgical anatomy. There are tumours which grow cranially close to the skull base, tumours that originate within the skull base and secondarily extend into the PPS, and vice versa from the PPS across the skull base. In these cases, the surgical space for resection is obtained at the expense of the bony skull base that is included in the approach thus allowing complete tumour control. The largest tumours offer a further example, as in jugular paraganglioma extending into the PPS, in extracranial-intracranial tumours crossing the skull base, or in malignancies like advanced tumours of the parotid and minor salivary glands, where combining the cervico-parotid surgical corridor with a trans-mastoid or trans-petrous or sub-temporal approach allows cranial macroscopic and potential microscopic diffusion of tumour to be followed. In this perspective of improved exposure and safety of oncologic margins, skull base microsurgery represents progress in both primary and secondary tumours of the PPS 22-24. Microsurgical PCR and CR can be considered codified procedures, while further experience is expected to show whether the medial aspect of large tumours is better handled adding a trans-oropharyngeal or trans-nasal approach, either microsurgical or endoscopic 10,25-27. On the other hand, growing evidence is in favour of the declining role of trans-mandibular approaches 28-32.

Conclusions

The PPS as a transit zone between the skull base and neck presents a high number of tissues from which tumours originate. Constrained anatomy and non-expendable nerves and vessels make surgery difficult and dependent on precise diagnosis and planned resection. In our experience, PPS tumours were submitted to 2 basic microsurgical procedures, pericapsular resection and the wider conservative resection of the PPS. The goal of setting a rationale between preoperative diagnosis, approach and final pathology involved separating the lesions with a “safe” preoperative diagnosis from those with “unsafe” diagnosis, recurrent cases, and malignancies. The first category included benign tumours, amenable to successful PCR, where final pathology confirmed preoperative diagnosis of schwannoma, paraganglioma, and lipoma in all but one case. The second category included the other rare benign tumours, tumours with uncertain diagnosis, misdiagnosed malignancies, recurrent cases, and malignant tumours, which were all submitted to broader conservative resection of the PPS. The adequacy of the approach was supported by the completeness of resection that occurred in the groups of “safe” diagnosis, benign “unsafe”, recurrent, and low-grade malignant tumours, while failures occurred in more aggressive malignant tumours (intrinsically rising unsolved issues), and a few recurrent PA. Microsurgery seems to allow safer handling of the dissection on nerves, vessels and critical planes, advancing in narrow corridors and including the skull base to obtain proper control of the cranial pole of the lesion. Combined with the principles of oncological lateral skull base surgery, microsurgery represents a step forward to enhance the indications to the transcervical-parotid approach.

Acknowledgements

The authors are grateful to Mrs. Alison Garside for editing the English version of this manuscript.

Conflict of interest statement

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Funding

The authors received no funding for this article.

Author contributions

AM: conceptualisation, design, conduct, manuscript drafting, supervision; LF: conceptualisation, design, conduct, manuscript drafting, supervision; EZ: conceptualisation, design, conduct, manuscript drafting, supervision.

Ethical consideration

The research was conducted ethically, with all study procedures being performed in accordance with the requirements of the World Medical Association’s Declaration of Helsinki.

All patients signed an informed consent form regarding the processing and publication of their data, which were examined in agreement with the Italian privacy and sensitive data laws, and the internal regulations of the University Hospital of Padua.

History

Received: May 20, 2024

Accepted: September 4, 2024

Figures and tables

Figure 1. Vagal paraganglioma at MRI: A) T1 contrast-enhanced sequence; B) T2 sequence.

Figure 2. Deep lobe parotid pleomorphic adenomas at MRI: A) right side; B) left side.

Figure 3. Recurrent parotid pleomorphic adenomas at MRI: A) right side; B) left side.

Figure 4. Malignant schwannoma, right side, at MRI.

Figure 5. Carcinoma ex pleomorphic adenoma, right side, at MRI.

Figure 6. Recurrent sarcoma of the left PPS, at MRI.

Figure 7. The clinical process from diagnosis to surgical approach in first diagnosis PPS tumours. PCR: pericapsular resection; CRPPS: conservative resection of PPS; RRPPS: radical resection of PPS; PA: pleomorphic adenoma.

| Parapharyngeal lesions | Total cases (recurrent tumours at diagnosis) |

|---|---|

| Carotid paraganglioma | 29 |

| Vagal paraganglioma | 23 |

| Pleomorphic adenoma | 17(3) |

| Lipoma | 5 |

| Schwannoma | 10 |

| Malignant schwannoma | 2(1) |

| Malignant low grade schwannoma | 1(1) |

| Melanoma | 1 |

| Haemangiopericytoma | 1(1) |

| Carcinoma ex pleomorphic adenoma | 2(2) |

| Lymphoma | 1(1) |

| Rabdomyosarcoma | 1(1) |

| Myoepitelioma | 2 |

| Aspecific lymphadenitis in nasopharyngeal carcinoma, after chemoradiotherapy | 1 |

| Sarcoma | 1(1) |

| Total | 97(11) |

| Pathology | No. of FD cases | No. of REC cases | Surgical procedure | No. of relapse | Incorrect preoperative diagnosis | Malignant tumours at pathology vs preoperative diagnosed benign tumours |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Paraganglioma | 52 | 52 PCR | / | |||

| Schwannoma | 10 | 10 PCR | / | |||

| Lipoma | 5 | 4 PCR | / | * | ||

| 1 CR | Teratoma | |||||

| Pleomorphic adenoma | 14 | 14 CR | 2 | |||

| 3 | 3 CR | 2 | ||||

| Myoepitelioma | 2 | 1 CR | / | Pleomorphic adenoma | ||

| 1 PCR | / | |||||

| Melanoma | 1 | 1 CR | 1 | Pleomorphic adenoma | 1 | |

| Malignant schwannoma | 1 | 1 CR | 1 | Neurofibroma | 1 | |

| 1 | 1 CR | 1 | ||||

| Low-grade malignant schwannoma | 1 | 1 CR | / | Haemangioma | 1 | |

| Post CRT lymphoadenitis | 1 | 1 RR | / | Nasopharyngeal carcinoma recurrence after CRT | ||

| Carcinoma ex pleomorphic adenoma | 2 | 2 CR | / | Recurrent pleomorphic adenoma | 2 | |

| Lymphoma | 1 | 1 CR | / | |||

| Sarcoma | 1 | 1 CR | / | |||

| Rhabdomyosarcoma | 1 | 1 CR | / | |||

| Haemangiopericytoma | 1 | 1 CR | 1 | Fusiform cell malignant neoplasm | ** | |

| Total | 86 | 11 | 67 PCR | 8 | 8 / 97 | 5 |

| 29 CR | ||||||

| 1 RR | ||||||

| *Pre- and postoperative benign tumour wrongly diagnosed in the preoperative setting; **Pre- and postoperative malignant tumour wrongly diagnosed in the preoperative setting; FD: first diagnosis; REC: recurrences; PCR: pericapsular resection; CR: conservative resection; RR: radical resection. | ||||||

References

- Mosciaro O. I Tumori Parafaringei. Studio Forma; 1994.

- Friedmann W, Katsantonis G, Cooper M. Stylohamular dissection. Laryngoscope. 1981;91:1880-1891.

- Guerrier Y, Peringuey J. Les tumeurs parapharyngées. Les cahiers d’O.R.L. 1983;10:855-909.

- Olsen K. Tumors and surgery of the parapharyngeal space. Laryngoscope. 1994;104:1-28.

- Makeieff M, Quaranta N, Guerrier B. Tumeurs parapharyngées. Encycl Méd Chir Oto-rhino-laryngologie. 2000;20:605-C.

- Terminologia Anatomica. Thieme; 1998.

- van Hees T, van Weert S, Witte B. Tumors of the parapharyngeal space: the VU University Medical Center experience over a 20-year period. Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol. 2018;275:967-972. doi:https://doi.org/10.1007/s00405-018-4891-x

- Pensak M, Gluckmann J, Shumrick K. Parapharyngeal space tumours: an algorythm for evaluation and management. Laryngoscope. 1994;104:1170-1173. doi:https://doi.org/10.1288/00005537-199409000-00022

- Jose D, Mohiyuddin S, Mohammadi K. Extra-parotid pleomorphic adenoma and low-grade salivary malignancy in the head and neck region. Cureus. 2023;15. doi:https://doi.org/10.7759/cureus.39463

- Wakely P. Mesenchymal neoplasms of the parotid gland and parapharyngeal space: an FNA cytologic study of 22 nonlipomatous tumors. Cancer Cytopathol. 2022;130:443-454. doi:https://doi.org/10.1002/cncy.22562

- Farrag T, Lin F, Koch W. The role of pre-operative CT-guided FNAB for parapharyngeal space tumours. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2007;136:411-414. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.otohns.2006.10.006

- Joshi P, Joshi K, Nair S. Surgical management of parapharyngeal tumors: our experience. South Asian J Cancer. 2021;10:167-171. doi:https://doi.org/10.1055/s-0041-1731580

- Som P, Curtin H. Lesions of the parapharyngeal space. Role of the MR imaging. Otolaryngol Clin North Am. 1995;28(3):515-541.

- Som P, Biller H, Lawson W. Tumors of the parapharyngeal space. Preoperative evaluation, diagnosis and surgical approaches. Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol. 1981;90:3-15. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/00034894810901s301

- Som P, Biller H, Lawson W. Parapharyngeal space masses: an updated protocol based upon 104 cases. Radiology. 1984;153:149-156. doi:https://doi.org/10.1148/radiology.153.1.6089262

- Bradley P. Pleomorphic salivary adenoma of the parotid gland: which operation to perform?. Curr Opin Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2004;12:69-70. doi:https://doi.org/10.1097/00020840-200404000-00002

- Bozza F, Vigili M, Ruscito P. Surgical management of parapharyngeal space tumors: results of 10-year follow-up. Acta Otorhinolaryngol Ital. 2009;29:10-5.

- Chen R, Cai Q, Liang F. Oral core-needle biopsy in the diagnosis of malignant parapharyngeal space tumours. Am J Otolaryngol. 2019;40:233-235. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.amjoto.2018.11.005

- Li X, Li J, Zheng N. Ultrasound fusion-guided core needle biopsy for deep head and neck space lesions: technical feasibility, histopathologic yield, and safety. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 2023;44:180-185. doi:https://doi.org/10.3174/ajnr.A7776

- Zanoletti E, Marioni G, Nicolai P. The contribution of oncological lateral skull base surgery to the management of advanced head-neck tumors. Acta Otolaryngol. 2023;143:101-105. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/00016489.2023.2174270

- Roh J. Extracapsular dissection via single cervical incision for parotid pleomorphic adenoma. Clin Oral Investig. 2023;28. doi:https://doi.org/10.1007/s00784-023-05420-5

- Mazzoni A, Sanna M. A postero-lateral approach to the skull base; the petro-occipital transigmoid approach. Skull Base Surg. 1995;5:157-165. doi:https://doi.org/10.1055/s-2008-1058930

- Suárez C, Rodrigo J, Mendenhall W. Carotid body paragangliomas: a systematic study on management with surgery and radiotherapy. Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol. 2014;271:23-34. doi:https://doi.org/10.1007/s00405-013-2384-5

- Mazzoni A, Franz L, Zanoletti E. Microsurgery in carotid body paraganglioma. Acta Otorhinolaryngol Ital. 2024;44:76-82. doi:https://doi.org/10.14639/0392-100X-N2761

- Ferrari M, Schreiber A, Mattavelli D. Surgical anatomy of the parapharyngeal space: multiperspective, quantification-based study. Head Neck. 2019;41:642-656. doi:https://doi.org/10.1002/hed.25378

- Lombardi D, Ferrari M, Paderno A. Selection of the surgical approach for lesions with parapharyngeal space involvement: a single-center experience on 153 cases. Oral Oncol. 2020;109. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.oraloncology.2020.104872

- Schreiber A, Mattavelli D, Accorona R. Endoscopic-assisted multi-portal compartmental resection of the masticatory space in oral cancer: anatomical study and preliminary clinical experience. Oral Oncol. 2021;117. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.oraloncology.2021.105269

- Basaran B, Polat B, Unsaler S. Parapharyngeal space tumours: the efficiency of a transcervical approach without mandibulotomy through review of 44 cases. Acta Otorhinolaryngol Ital. 2014;34:310-316.

- Arshad H, Durmus K, Ozer E. Transoral robotic resection of selected parapharyngeal space tumors. Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol. 2013;270:1737-1740. doi:https://doi.org/10.1007/s00405-012-2217-y

- Battaglia P, Turri-Zanoni M, Dallan I. Endoscopic endonasal transpterygoid transmaxillary approach to the infratemporal and upper parapharyngeal tumors. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2014;150:696-702. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/0194599813520290

- Rubin F, Laccourreye O, Weinstein G. Transoral lateral oropharyngectomy. Eur Ann Otorhinolaryngol Head Neck Dis. 2017;134:419-422. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.anorl.2017.06.002

- Maglione M, Guida A, Pavone E. Transoral robotic surgery of parapharyngeal space tumours: a series of four cases. Int J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2018;47:971-975. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijom.2018.01.008

Downloads

License

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

Copyright

Copyright (c) 2025 Società Italiana di Otorinolaringoiatria e chirurgia cervico facciale

How to Cite

- Abstract viewed - 780 times

- PDF downloaded - 153 times