Otology

Vol. 45: Issue 3 - June 2025

Granulomatosis with polyangiitis presenting as isolated ear involvement: a case series and literature review

Abstract

Objective. To describe the clinical characteristics and outcomes of patients affected by granulomatosis with polyangiitis (GPA) presenting with isolated ear involvement.

Methods. A retrospective review of patients affected by GPA and treated at the University of Brescia, Italy, from 2002 to 2023 was conducted. Only patients with exclusive otologic manifestation as first presentation were included.

Results. Among 610 patients with antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibody-associated vasculitis (AAV) diagnosed and followed at our Institution, 6 (0.8%) presented with exclusive ear involvement as first presentation, all affected by GPA. Most frequently patients presented with otitis media with effusion, sensorineural or mixed hearing loss, and dizziness. Two patients developed systemic symptoms. All patients experienced at least a partial recovery of middle ear function after starting immunosuppressive therapy.

Conclusions. AAVs rarely show initial presentation as isolated ear involvement, and more commonly present as otitis media with hearing loss that is unresponsive to conventional therapy. Once an AAV is suspected, surgery should be avoided since further damage can be caused by local iatrogenic inflammation sustained by the underlying condition. Local improvement is generally seen after the start of immunosuppressive therapy.

Introduction

Antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibody (ANCA)-associated vasculitis (AAVs) is a group of systemic diseases histologically characterised by necrotising lesions. ANCAs are antibodies against neutrophil and monocyte lysosomal enzymes, specifically myeloperoxidase (MPO) and proteinase 3 (PR3), corresponding to p-ANCA and c-ANCA, respectively. These antibodies can cause the release of lytic enzymes and vascular inflammation. AAVs are classified according to histological features and size of vessels involved. AAVs affecting small vessels include granulomatosis with polyangiitis (GPA, formerly called Wegener’s granulomatosis), microscopic polyangiitis (MPA), and eosinophilic granulomatosis polyangiitis (EGPA, formerly called Churg-Strauss syndrome) 1.

The main organs involved in GPA are the upper respiratory tract, kidneys, and lungs. Ear involvement in GPA is well known and its prevalence varies from 19% to 61% of patients, with chronic otitis media with effusion (OME) as the most common presentation (in up to 90% of cases) 2,3. Although the otoscopic presentation does not significantly vary from an OME secondary to simple Eustachian tube dysfunction, otitis media caused by AAV (OMAAV) is typically resistant to common treatments, including steroids, antibiotics, and placement of a ventilation tube.

Sensorineural hearing loss (SNHL) is the second most common otologic presentation, reported in up to 43% of patients with GPA, and mostly associated with a conductive loss secondary to OME or tympanic membrane perforation 4,5. Typically, a standard audiogram shows a flat HL or a gently sloping high-frequency loss. Less frequently, patients may present with chronic suppurative otitis media (24% of cases), facial palsy (8%), vertigo, and hypertrophic pachymeningitis 4,6,7.

Although GPA typically presents with a various combination of upper respiratory tract, pulmonary and renal manifestations, isolated otologic disorders can be observed as the first manifestation of the disease 8. The aim of this study is to retrospectively describe a monocentric case series and perform a literature review of GPA presenting with isolated ear involvement as first manifestation.

Materials and methods

We performed a retrospective charts review of patients affected by AVVs followed at the Units of Otorhinolaryngology – Head and Neck Surgery and Nephrology of the ASST Spedali Civili of Brescia, University of Brescia, Italy, from 2002 to 2023. Inclusion criteria were: a) isolated ear involvement as the first disease manifestation; b) diagnosis of GPA either by ANCA titer or tissue biopsy; c) age at diagnosis > 18 years. Patients with any other concurrent disease manifestation at the time of first diagnosis were excluded.

Data were collected in a dedicated anonymised database and the study was conducted in accordance with the declaration of Helsinki. Demographic, clinical, radiological, histopathological, and follow-up data were retrieved and expressed in terms of mean, range of values, and percentages. In addition, a comprehensive review of studies published from 1991 to 2023 and describing cases of GPA presenting as isolated ear involvement was conducted.

Results

Six (0.8%) of 610 patients with AAVs followed at our Institution between 2002 and 2023 met the above mentioned inclusion criteria. Details of this cohort of patients are shown in Table I. Four patients were males (66.7%) with a mean age of 48 years (range, 19-75). All patients were affected by GPA.

Clinical presentation and symptoms

All patients were referred to our Institution for otologic conditions unresponsive to conventional therapies, with no other symptoms attributable to GPA.

At presentation, microscopic examination of the ear revealed OME in 5 cases (83.3%), which was bilateral in 3 and associated with otitis externa in one. The remaining patient presented with unilateral acute suppurative otitis media.

Two patients (33.3%) presented with facial nerve palsy, as a complication of unilateral acute suppurative otitis media in one case, and occurring after a canal wall down mastoidectomy and tympanoplasty performed elsewhere in the other case.

In all cases pure tone audiometry revealed a mixed HL at least in one ear. In 2 patients (33.3%) contralateral profound SNHL was found. All patients underwent clinical vestibular evaluation. Vestibular dysfunctions were present in 2 patients (33.3%); bedside evaluation with videonystagmoscope showed spontaneous nystagmus in both patients (grade II in one case, grade III in the other one). Ear symptoms were present for at least 2 months and up to 2 years prior to diagnosis of GPA.

Diagnosis, treatment, and outcomes

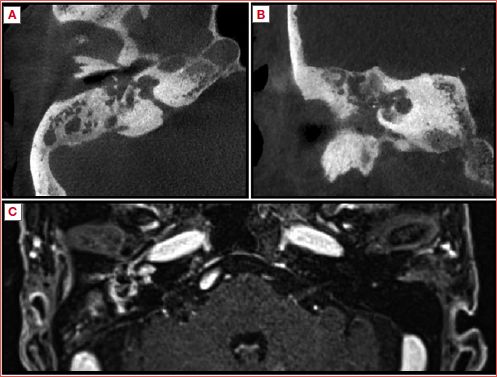

All patients in the present case series underwent temporal CT scan because of the clinical presentation (e.g. facial palsy, sudden decrease in bone conduction) or for long-lasting symptoms. In all cases, the scans showed middle ear and mastoid opacification. Further investigation with magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) was performed if complications were present or suspected. MRI showed middle ear pathologic mucosal enhancement in all patients. In the patient presenting with acute otitis media and ipsilateral facial palsy, both CT and MRI scans showed coalescent mastoiditis and a pathologically increased enhancement of the facial nerve in contrast-enhanced T1-weighted MRI. In all patients, conservative treatment with oral antibiotics and corticosteroids was initially attempted. In 5 cases (83.3%) myringotomy with ventilation tube insertion was performed (bilaterally in 4, unilaterally in one) (Tab. I). In the above mentioned patient with facial palsy not responding to conservative treatment, a cortical mastoidectomy was performed. Despite initial partial control of symptoms, no significant improvement was achieved in any of these cases.

Because of the lack of clinical improvement, an autoimmune disorder was suspected and ANCA assay performed, allowing for early diagnosis of GPA in 4 patients. Anti-PR3 (c-ANCA) was titrated in 4 (66.6%) and anti-MPO (p-ANCA) in one (16.6%) patient. In one case antibody assay was negative and the diagnosis of GPA was made only after middle ear mucosal biopsy under local anaesthesia. Pseudomonas aeruginosa and Staphylococcus aureus were isolated in the auricular drainage in one (16.6%) and 2 (33.3%) patients, respectively.

All patients were referred to an immunologist and nephrologist for evaluation to exclude involvement of other organs and systems. In our series, none of the patients had any other localisation of disease at diagnosis.

After the initiation of immunosuppressive therapy, middle ear function was restored in all patients, whereas long-term audiologic outcomes varied widely (Tab. I). One patient recovered normal hearing and in 2 patients a mild conductive HL persisted, whereas in 3 cases the disease caused severe-profound mixed HL. Regarding facial palsy, one patient improved from a grade IV to a grade II palsy according to the House Brackmann classification, while the patient who had facial palsy after surgery performed elsewhere had a full recovery, suggesting that its onset was more likely related to progression of GPA rather than a surgical injury. No residual vertigos were reported.

Two patients with persistent profound SNHL received a cochlear implant (CI), with both achieving satisfactory hearing results: speech recognition tested one year after surgery scored 60% at 55 dB for one patient and 50% for the other. Two patients (33.3%) later developed systemic symptoms during follow-up. One of these died from complications of systemic disease.

Discussion

GPA only rarely initially manifests with exclusive otologic involvement8. Most experiences, particularly those with large cohorts, discuss the ear-related manifestations of GPA 9,10, while literature addressing GPA with exclusive ear involvement is lacking. Diagnosis is challenging and generally suspected after resistance to many therapeutic attempts, although it is often delayed. In our series, 3 of 6 patients were diagnosed with GPA at least 3 months after referral to our department (Tab. I). Early diagnosis and therapy, however, can play a pivotal role in improving ear manifestations and prevent the onset of systemic vasculitis. Differential diagnosis includes: middle ear cholesteatoma, cholesterol granuloma, eosinophilic otitis media (EOM), tuberculosis, malignant otitis externa (skull base osteomyelitis), neoplasms, and other autoimmune diseases 9,10. Key examinations to achieve correct diagnosis comprise nasal endoscopy, which should nonetheless be performed in any case of otitis media or middle ear impairment 11, careful laryngoscopy, especially looking for possible subglottic stenosis, microbiological and histological examinations, ANCA tiers and imaging with CT without contrast enhancement and MRI with or without contrast enhancement. MRI is not required for the diagnosis of OME and acute otitis media, but should be performed when complications are suspected, although it is helpful in differentiation from cholesteatoma or neoplasm. Furthermore, when an autoimmune disease like GPA is suspected, nephrological/immunological evaluation is mandatory to properly investigate involvement of other organ systems.

In 2016, Harbuchi et al. analysed the clinical features of OMAAV in a large retrospective analysis 9. In that study, the authors proposed criteria for diagnosis of OMAAV, which were then refined in a review published in 2021 (Tab. II) 10. The experience in the literature regarding systemic vasculitis initially presenting as isolated ear involvement is summarised in Table III. Overall, 66 patients have been described in 36 publications.

ANCA are usually measured by indirect immunofluorescence, with 2 distinct staining patterns. c-ANCA (or PR3-ANCA), most associated with GPA, are directed against proteinase-3 (PR3) producing a cytoplasmic staining pattern. p-ANCA (or MPO-ANCA), less frequently found in GPA, are directed against myeloperoxidase, producing a perinuclear staining pattern 1.

In our series and in the review of the OMAAV literature (Tab. III), most patients were c- and/or p-ANCA positive, with c-ANCA being more frequent. Negative ANCA titres do not always rule out GPA, especially in the first isolated disease manifestation: in one patient in our series, the ANCA titre became positive only months after the first manifestation of OMAAV. ANCA titre varies in relation to disease status, thus measuring the activity and severity of the disease: c-ANCA can be found in more than 90% of patients with active GPA, decresing to 60-65% in cases of limited disease, and detectable in only 30-40% of patients with inactive disease 45-47. Consequently, a negative c-ANCA test cannot be considered an exclusion criterion for GPA in the diagnostic work-up 48. Furthermore, the corticosteroid therapy commonly prescribed as a first-line treatment in isolated OMAAV may reduce the ANCA titre 15. To overcome the low sensitivity of serum ANCA in isolated OMAAV, Morita et al. 49,50 demonstrated that the diagnosis and severity of OMAAV could be defined through the detection and quantification of MPO-DNA complex in ear drainage samples, regardless of the status of serum ANCA or immunosuppressive therapy.

Moreover, the difficulty in obtaining suitable ear tissue specimens for histologic examination in OMAAV should be considered: middle ear biopsy has a lower positivity rate than nasal or lung biopsies 6. Therefore, if OMAAV is suspected, nasal endoscopy can also help to identify nasal lesions that could be biopsied. Vascular submucosal dilatation, mucosal swelling, white submucosal nodules, bloody patches, and polypoid nodules are typical lesions of active nasal GPA 51.

It is also well-known that GPA is associated with bacterial infection, especially Staphylococcus aureus. Up to 60-80% of patients affected by GPA harbour such a pathogen in nasal mucosa (compared to 30-40% of the general population). The specific pathophysiological mechanism that relates GPA to this bacterium is still not fully understood, but its chronic presence seems to negatively affect the disease course and risk of relapse 52. One possible explanation for the high prevalence of Staphylococcus aureus in the nasal mucosa of patients with GPA is the lower IgG responses compared to the general population 53. Literature on the presence of Staphylococcus aureus specifically in OMAAV ears is lacking. In our series, it was found in the microbiological evaluation of ear drainage in 2 of 6 patients. Its presence in ear secretions should be considered in the diagnostic work-up of suspected OMAAV.

Concerning HL, patients with isolated OMAAV can be affected by either conductive HL, secondary to involvement of the middle ear or Eustachian tube mucosa 54, SNHL secondary to cochlear inflammation 55, or a combination of both. In our experience, all patients were affected by mixed HL. Regarding the pathophysiology of SNHL, GPA-related vasculitis involving cochlear microcirculation seems to play a critical role in determining imbalance of ions and fluid and consequent disruption of cochlear endo-lymphatic potential. Some authors have suggested that the early ’reversible’ state of SNHL might be caused by a reduction in K+ ions in the endolymph due to vasculitis and consequent ischaemia of the stria vascularis 18. The reversible damage to hair cells during the initial phase of the disease is demonstrated by the improvement of bone conduction generally observed after starting the immunosuppressive therapy. However, untreated or long-term effects of local inflammation may lead to dysfunction of fibrovascular coupling, thus determining permanent damage of the hair cells 4. Long-term middle ear disease involvement is demonstrated by post-mortem histopathologic studies of deaf patients affected by OMAAV, showing tympanic granulation tissue invading the round window niche and membrane, and eventually projecting into the scala tympani 54.

Nakanaru et al., in an analysis of 34 patients with GPA and ear involvement, identified 3 types of otologic symptoms: chronic otitis media (COM), OME, and SNHL 56. Interestingly, the authors reported that all patients with COM were PR3-ANCA positive, whereas 89% of patients in the MPO-ANCA group presented with OME. No difference in the frequency of SNHL between the 2 ANCA groups was reported. In our series, all patients with COM were also PR3-ANCA positive and the only MPO-ANCA patient presented OME. Morita et al. 57 analysed 31 patients with OMAAV and noted that 35% had vestibular symptoms: chronic dizziness (CD) in 73% and an acute vertigo attack (AVA) in the remaining 27%. In our experience, 2 of 6 patients (33.3%) had vestibular symptoms: one patient presented AVA and the other CD (Tab. I).

In our series, 2 patients presented unilateral facial palsy. In the literature, facial palsy is described as a rare manifestation associated with OMAAV, secondary to nerve compression in its tympanic portion, especially in case of a dehiscent Fallopian canal, or to vasculitis of the vasa nervorum, and has been reported in 8% of cases 4. In fact, it is well known that GPA can affect nervous system leading to nerve neuropathies 3. Several case reports showed disease progression or failure of resolution despite myringotomy or mastoidectomy 19,28,58. In a report by Kukushev et al. on 2 patients with OMAAV and facial palsy, surgical decompression of the facial nerve performed before diagnosis of GPA and in association with corticosteroids showed good results 29. In our case series, the patient with onset of facial palsy at presentation underwent this procedure and, later, started immunosuppressive therapy, with partial improvement of the palsy. Surgical decompression was made on mastoid tract of the nerve, which showed a pathological enhancement in MRI. However, since the activation of neutrophils is necessary to generate ANCAs, invasive surgical procedures might trigger inflammation 4, thus leading to further disease progression; accordingly, several experiences in the literature have reported that ear surgeries such as tympanoplasty or mastoidectomy performed during the active phase of vasculitis are not effective and may worsen the disease 4,10,30,33,34. In our opinion, also in accordance with Harabuchi’s recommendations for management of OMAAV 10, when an autoimmune disease is suspected, any type of extensive surgery should be avoided, since it is potentially harmful, and early initiation of immunosuppressive therapy should be favoured.

Early diagnosis may benefit from specific anomalies on radiological studies (Cover figure). The review by D’Anza et al. reported that sinus CT and MRI in GPA detect pathological findings in most patients: mucosal thickening, osteitis, bony destruction, septal erosion, sinus obliteration, and orbital involvement were the most common observations 59.

Immunosuppressive therapy should be started as soon as possible to prevent or delay the onset of systemic disease. In long-term follow-up studies of localised GPA, it has been reported that 10% of patients develop systemic disease and 46% relapse despite therapy 60,61. In our series, 2 of 6 patients developed systemic symptoms after about 8 and 12 weeks. Among patients with OMAAV included in the review of the literature (Tab. III), most recovered or had improvement of symptoms 4,6,8,12,14-16,18-21,23,24,26,30-44, but in a non-negligible proportion of patients (n = 9) further systemic progression of disease, even to death (n = 6), was recorded 13,19,25,28,34. In these patients, the time interval between the onset of OMAAV and systemic progression ranged from 8 to 24 weeks. However, in the same patients, diagnosis of GPA (reached only after systemic manifestations) or initiation of immunosuppressive treatment were common, further highlighting the importance of early diagnosis and treatment.

Treatment of OMAAV with antibiotics is usually ineffective. Only control of the disease with corticosteroids and immunosuppressive drugs, such as cyclophosphamide, azathioprine and methotrexate, can achieve hearing improvement 10. Okada et al. demonstrated that immune activity, in terms of soluble interleukin 2 receptor serum levels, in patients with systemic and localised (to the ear) OMAAV is equivalent and ear damage is worse in the localised group 62. Therefore, treatment for OMAAV may need to be equal in intensity to that for systemic AAV. Furthermore, in a study published in 2019 63, the same authors demonstrated that rituximab, a murine/human chimeric monoclonal antibody that binds to the transmembrane protein CD20 and already recommended by the European League Against Rheumatism in selected patients for the therapy of systemic AVVs 64, can be effective and safe for intractable OMAAV for which remission with other drugs cannot be achieved.

All patients in our series improved after initiating immunosuppressive therapy, whereas the long-term audiological outcomes varied. In one case there was complete recovery of hearing, whereas a slight conductive HL and a severe mixed HL persisted in 2 and 3 cases, respectively. According to the literature, patients frequently experience at least a residual conductive HL in the long term, even if disease control had been reached 4,6,8,14,15,17,18,20-24,26-29,33,35-38,41-44 (Tab. I). In a recent study by Iwata et al. on 32 patients with OMAAV, younger age, male gender, use of intravenous corticosteroids, shorter period from onset to diagnosis and therapy, and better hearing threshold at diagnosis were good prognosticators of hearing outcomes 65. In 2022, Tabei et al. reported worse hearing preservation with steroids and immunosuppressive therapies in patients with AAVs with otitis complicated by hypertrophic pachymeningitis (HPM), which is more frequently observed when there is a delay in start of treatment 66. It is still unclear, however, if a poorer hearing result is associated with HPM because of cochlear nerve involvement or as a mere consequence of an untreated prolonged OMAAV.

As recommended by Harabuchi et al., cochlear implantation (CI) should be considered as treatment for OMAAV that progresses to bilateral profound deafness 10; recent experience show good results, even in inner ear with mild cochlear calcification at preoperative CT 29,41,44 (Tab. III). Watanabe et al. 67 reported on a series of 4 patients affected by OMAAV with profound HL who required CI; in 3 patients (75%), language understanding after the procedure was poor, probably due to spiral ganglion degeneration related to disease progression. In fact, in these patients preoperative MRI showed clear enhancement of the cochlea. Thus, time to deafness, contrast-enhanced MR and CT findings seem to be important for predicting the prognosis of CI for OMAAV with total HL 10,44. In our experience, 2 patients required CI, with MRI and CT showing a normal inner ear in both cases, and both procedures were successful. Regarding surgical technique, in both patients a subtotal petrosectomy according to Fisch 3 was performed in order to reduce the risk of complications and favour the clinical outcome of the procedure. The good functional results obtained are still maintained after a follow-up of 3 years in one case and for one year in the other.

Study limitations

Despite the high volume of patients affected by AAVs followed at our Institution, only 0.8% presented with exclusive ear disease as first presentation. The present study was therefore limited to a descriptive report of the clinical, audiologic characteristics and outcomes of this subgroup.

Conclusions

GPA can often involve the ear and, in rare cases, the presentation may be an isolated initial sign. It is important to consider GPA in the differential diagnosis of otitis media associated with progressive HL without improvement after conventional therapy and ventilation tube placement. ANCA titres, imaging, and microbiology may be helpful in diagnosis. Immunosuppressive therapy should be started as soon as possible when OMAAV is suspected to prevent irreversible middle and inner ear damage and the onset of systemic disease. Surgery should be avoided since the local inflammatory response may further increase local disease progression.

Conflict of interest statement

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Funding

This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Author contributions

SZ, MT, TS: designed the study, supervised and participated in data collection, wrote the initial article draft; GT: collaborated to data collection and analysis and to the main manuscript drafting; ST: collaborated to study design and manuscript drafting; LORDZ: supervised study design, data collection and analysis and manuscript drafting; NN, GAG: collaborated to data collection and critically reviewed the article; LORDZ, CP: supervised the overall work, guided the bibliographic research, and contributed to the final version of the manuscript. All authors contributed to manuscript drafting and approved the final version.

Ethical consideration

As a case series, the present research did not require approval of Ethics Committee. Informed consent was collected prior to surgery from each patient (all cases underwent myringotomy and ventilation tube insertion and/or cochlear implant positioning in our institution) for study participation and data publication according to the Italian laws. All study procedures were performed ethically, in accordance with the requirements of the World Medical Association’s Declaration of Helsinki, without affecting patients care in any way.

History

Received: March 16, 2024

Accepted: October 16, 2024

Figures and tables

| Patient | Age at presentation, gender | Oto-audiological findings at presentation | Facial palsy | Vestibular dysfunction | Imaging | ANCA titre | Surgery or biopsy | Microbiology | Time between presentation and diagnosis | Therapy | Outcome (after immunosuppressive therapy) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 75, F | Bilateral OME.Right severe mixed HL. Left sudden profound SNHL | No | Yes | CT: ME/mastoid opacification | Negative | Middle ear biopsy (diagnostic) | Staphylococcus aureus (ear) | 6 months | At presentation: systemic corticosteroid, antibiotics and bilateral VT | Partially improved: right moderately severe mixed HL, left profound HL | |

| MR: ME mucosal enhancement | After diagnosis: rituximab | Cochlear implant 1 year after diagnosis. Satisfactory audiological results | ||||||||||

| 2 | 52, M | Unilateral (left) OME with moderate-severe mixed HL | No | No | CT: ME/mastoid opacification | Anti-MPO-ANCA | No | Staphylococcus aureus (ear, nasal) | 1 year | At presentation: systemic corticosteroid and left VT | Improved: at 3 years, mild mixed HL on left side | |

| MR: ME mucosal enhancement | After diagnosis: rituximab | |||||||||||

| 3 | 19, F | Previous left suppurative otitis media treated elsewhere with CWD mastoidectomy and tympanoplasty, residual ipsilateral mixed moderate HL. Right OME | Yes, left (after surgery) – grade IV according to House Brackmann classification | Yes | CT (elsewhere): ME/mastoid opacification | Anti-PR3-ANCA | No | / | 2 months | At presentation: systemic corticosteroid, antibiotics and bilateral VT | Improved (ear): at 5 months, left mild CHL.Complete recovery of facial palsy | |

| Previous left suppurative OM treated with CWD mastoidectomy 2 months before | After diagnosis: rituximab | Systemic involvement (pericarditis and renal failure) occurred 2 months after ear symptoms presentation | ||||||||||

| 4 | 35, M | Bilateral OME with severe mixed HL | No | No | CT: ME/mastoid opacification | Anti-PR3-ANCA | No | / | 3 months | At presentation: systemic corticosteroid, antibiotics and bilateral VT | Partially improved: at 2 years, persistent moderate bilateral mixed HL | |

| After diagnosis: rituximab and cyclophosphamide | ||||||||||||

| 5 | 60, M | Left acute suppurative otitis media with sudden severe SNHL | Yes, left – grade IV according to House Brackmann classification | No | CT: ME/mastoid opacification, mild mastoid bone erosion | Anti-PR3-ANCA | Cortical mastoidectomy | / | 2 months | At presentation: systemic corticosteroid, antibiotics and bilateral VT | Persistent bilateral profound HL | |

| Right mixed severe HL | MR: ME mucosal and mastoid tract of facial nerve enhancement | After diagnosis: rituximab and cyclophosphamide | Partial improvement of facial palsy (grade II) after 1 month | |||||||||

| Dead from progression of systemic disease after 8 months | ||||||||||||

| 6 | 48, M | Bilateral OME and external otitis, mixed severe HL | No | No | CT: ME/mastoid opacification, external ear canals soft tissues thickening | Anti-PR3-ANCA | No | Pseudomonas aeruginosa (ear) | 1 week | At presentation: systemic corticosteroid and antibiotics | Persistent bilateral severe-profound HL | |

| MR: diffuse and bilateral ME and external ear canals enhancement | Story of recurrent bilateral external otitis diagnosed elsewhere in the previous 2 years | After diagnosis: methotrexate, rituximab | Cochlear implant 2 years after diagnosis. Satisfactory audiological results. | |||||||||

| ANCA: anti-neutrophil cytoplasmic antibodies; CT: computed tomography; CHL: conductive hearing loss; CWD: canal wall down; CWU: canal wall up; F: female; HL: hearing loss; male; ME: middle ear; MPO: myeloperoxidase; MR: magnetic resonance; OME: otitis media with effusion; PR3: proteinase 3; SNHL: sensorineural hearing loss; VT: ear ventilation tube. | ||||||||||||

| OMAAV diagnostic criteria, proposed by Harbuchi et al.10 | |

|---|---|

| 1. At least one of the following clinical findings: | Intractable otitis media with effusion or granulation, which is resistant to antibiotics and insertion of tympanostomy tube |

| Progressive deterioration of bone conduction hearing levels | |

| 2. At least one of the following features: | Already diagnosed as AAV (GPA, MPA, EGPA) |

| Positivity for serum MPO- or PR3-ANCA | |

| Histopathology consistent with AAV, i.e., necrotising vasculitis predominantly affecting small vessels with or without granulomatous extravascular inflammation | |

| At least one of the following accompanying signs/symptoms of AAV-related involvement: | |

| Involvement of upper airway tracts other than ear, scleritis, lung, and/or kidney, facial palsy, hypertrophic pachymeningitis, multiple mononeuropathy, transient alleviation of symptoms/signs with administration of 0.5-1 mg/kg prednisolone and relapse with discontinuation of treatment | |

| 3. Exclusion of other types of intractable otitis media | |

| Authors | Number of cases | Age, gender | ANCA | Ear symptom | Therapy | Outcome | Hearing outcome |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ito et al., 1991 8 | 1 | 12, F | / | Left otalgia, moderate-severe HL and tinnitus | Cyclophosphamide, prednisolone | Improved | Improved: at 1 y, mild conductive HL |

| Hartl et al., 1998 12 | 1 | 45, M | c-ANCA positive | Bilateral OM and conductive moderate HL, facial palsy, otalgia | Cyclophosphamide | Improved | Not reported |

| Moussa et al., 1998 13 | 2 | 14, F | ANCA positive | 1 unilateral mastoiditis, right mixed severe HL, left conductive moderate HL | Cyclophosphamide, methylprednisolone | 1 died1 unknown | Not reported |

| 20, F | 1 left conductive severe HL, OME, facial palsy | ||||||

| Maguchi et al., 2001 14 | 1 | 36, F | p-ANCA positive | Bilateral tinnitus and fluctuant sensorineural HL (moderate on right, moderate-severe on left) | Methylprednisolone | Right ear recovery and persistent left HL | |

| Takagi et al., 2002 6 | 2 | 20, F | Both c-ANCA positive | Pt 1, bilateral AOM and mixed HL, severe on right side, moderate on left | Pt 1, Cyclophosphamide, prednisone | Pt 1, partially improved | Pt 1, persistent HL |

| 31, F | Pt 2, bilateral AOM and moderate conductive HL | Pt 2, Azathioprine, methylprednisolone | Pt 2, recovered | Pt 2, recovered | |||

| Takagi et al., 2004 15 | 6 | Range, 36-82 years | 6 p-ANCA positive | 6 ears mixed HL, 6 ears SNHL, 3 pts vertigo, 1 pt facial palsy, 5 pts OME | Cyclophosphamide, azathioprine, methylprednisolone | 4 ears complete recovery, 5 ears moderate recovery, 3 ears no change | |

| (5 F, 1 M) | |||||||

| Ferri et al., 2007 16 | 1 | 59, F | Both positive (not specified) | Bilateral OME and mixed mild-moderate HL, unilateral facial palsy | Cyclophosphamide, prednisolone | Recovered | Recovered: at 3 months, mild bilateral neurosensorial HL on high tones |

| Yildirim et al., 2008 17 | 1 | 65, M | ANCA negative | Right total sensorineural HL, left moderate sensorineural HL, tinnitus and vertigo and meningeal irritation | Intratympanic prednisolone, high dose of oral steroids, and methotrexate | Partially improved (meningeal enhancement reduced) | Partially improved: at 10 months, right profound HL (no improvement), left moderate HL (slightly improved) |

| Yamazaki et al., 2011 18 | 3 | Range, 55-67 years | 2 p-ANCA positive, 1 c -ANCA positive | OME, AOM, HL | Steroids, immunosuppressive therapy | All 3 pts improved | Improved (during remission): |

| (2 F, 1 M) | Pt 1: severe bilateral HL | Pt 1: right normal hearing, left moderate-mild HL | |||||

| Pt 2: right severe HL, left moderate HL | Pt 2: right mild HL, left normal hearing | ||||||

| Pt 3: right profound HL, left moderate-severe HL | Pt 3: right moderate HL, left normal hearing | ||||||

| Wierzbicka et al., 2011 19 | 7 | Range, 32-46 years | 7 c-ANCA positive | Mixed or sensorineural HL (6 bilateral, 1 unilateral, ranging from moderate to profound), 1 unilateral facial nerve palsy, 2 ear discharge | Steroids, cyclophosphamide, vincristine | 2 deaths | |

| (3 M, 3 F) | 3 hearing improvement and partial recovery of facial nerve palsy | ||||||

| 2 progressions of systemic disease | |||||||

| Sriskandarajh et al, 2012 20 | 2 | 36, M | 1 c-ANCA positive | Pt 1, right OME and mixed severe-profound HL | Prednisolone, methotrexate | Pt 1 recovered | Pt 1, at 4 months, right mild mixed HL |

| 62, M | Pt 2, right moderate-severe SNHL on the right and left severe mixed HL, perforation of tympanic membranes | Pt 2 symptoms improved | Pt 2, residual deafness | ||||

| Yoshida et al., 2013 4 | 8 | Range, 54-73 years (6 F, 2 M) | 6 p-ANCA positive, 2 c-ANCA positive | Mixed HL (7 bilateral, 1 unilateral), 3 facial palsy, 4 OME, 4 OMG | Prednisolone, cyclophosphamide | All 8 pts improved | Improved in 81% (13/16) of ears. Patients with hearing levels better than 95 dB improved with good speech discrimination, completely deaf ears did not recover |

| Lee et al., 2013 21 | 1 | 59, F | c-ANCA positive | Bilateral moderate-severe mixed HL, left facial palsy | Decompression of the left facial nerve and high dose steroids | Left facial expression recovery, persistent bilateral tympanic membrane perforation | Partially improved: |

| At 3 months, bilateral moderate-mild mixed HL | |||||||

| Uppal et al., 2014 22 | 1 | 16, F | c-ANCA positive | Left profound sensorineural HL | Cyclophosphamide + prednisolone and azathioprine (as maintenance agent) | Persistent profound left HL | |

| Costa et al., 2015 23 | 1 | 50, F | c-ANCA positive | Right mixed severe HL, left mixed profound HL, retraction-thickening of the tympanic membrane, fluid in the middle ear, otorrhea after ventilation tube | Cyclophosphamide, methylprednisolone | Improved | Right ear recovery (mild sensorineural HL on high frequencies), left ear partial recovery (residual moderate-severe HL) |

| Maniu et al., 2016 24 | 1 | 26, M | c-ANCA positive | Left facial palsy and mixed HL, bilateral OME, right AOM, OMG | CWU mastoidectomy and tympanoplasty, cyclophosphamide, methylprednisolone | Partially improved | Partial HL recover (not specified) |

| Jeong et al., 2016 25 | 1 | 40, M | c-ANCA positive | Bilateral facial palsy (first right, then left) and mixed HL, OMG, dizziness | Right facial nerve decompression, steroid, cyclophosphamide | Progression of systemic disease | Not reported |

| Kim et al., 2016 26 | 1 | 47, M | c-ANCA positive | Left facial palsy, bilateral mixed severe-profound HL and OME | Cyclophosphamide, steroids (both systemic and with intratympanic injections), rituximab | Improved | Partially improved: at 4 months, right mild HL, left persistent HL |

| Brown et al., 2016 27 | 1 | 38, F | c-ANCA positive | Bilateral OMG with perforation of the tympanic membrane and severe HL | Cyclophosphamide, prednisolone | Symptoms improved | Not improved: persistent HL. Satisfactory audiological results with bilateral hearing aids |

| Wawrzecka et al., 2016 28 | 1 | 56, F | c-ANCA increased (not frankly positive) | Bilateral thickening and perforation of the tympanic membrane, AOM, severe-profound mixed HL, facial palsy (left first) | Facial nerve decompression with cortical mastoidectomy, cyclophosphamide, steroids | ENT symptoms improved, death for systemic progression | At 2 months, bilateral sever-profound HL with minimal improvement |

| Elmas et al., 2017 29 | 1 | 29, M | c-ANCA positive | Recurrent bilateral OM with purulent otorrhea and moderate mixed HL | Methotrexate, steroids, infliximab, then right side subtotal petrosectomy and CI | Persistent left moderate mixed HL, progression of right SNHL, excellent language understanding ability result after CI | |

| Kukushev et al., 2017 30 | 2 | 32 M | 2 c-ANCA positive | Both pts unilateral HL, facial palsy, OMG, AOM and mastoiditis | Both patients cortical mastoidectomy and decompression of facial nerve, 1 methylprednisolone, azathioprine and cyclophosphamide, 2 methylprednisolone and rituximab | Facial palsy recovery | Not reported |

| 44 M | 1 recurrence of mastoiditis (revision mastoidectomy performed) | ||||||

| Wang et al., 2018 31 | 1 | 14, F | c-ANCA positive | Bilateral AOM, moderate-severe mixed HL and thickened tympanic membranes, right facial palsy | Methylprednisone, rituximab, cyclophosphamide | Partially improved (facial nerve palsy partial recover after 9 months) | Not reported |

| Mur et al., 2019 32 | 1 | 68, F | c-ANCA and p-ANCA positive | Bilateral otitis externa, left AOM, left facial palsy, bilateral HL | Rituximab, prednisone, azathioprine | Facial palsy spontaneously resolved | Not reported |

| Qaisar et al., 2019 33 | 1 | 50, M | c-ANCA positive | Right AOM, OMG and HL | Cortical mastoidectomy, high dose steroid | Improved (short term, long term unknown) | Not reported |

| Marszał et al., 2021 34 | 6 | Range, 31-43 years | 6 c-ANCA positive (1 late) | 4 unilateral HL and unilateral facial palsy, 2 bilateral HL and unilateral facial palsy | 3 cortical mastoidectomy, 2 CWU mastoidectomy and tympanoplasty, cyclophosphamide, steroid | 2 deaths | 4 improvement of the HL (not specified) |

| (3 F, 3 M) | 4 improved | ||||||

| Kousha et al., 2021 35 | 1 | 82, F | c-ANCA positive | Bilateral severe-profound mixed HL | Steroid, rituximab | Partially improved | Planned CI due to residual permanent HL |

| Djerić et al., 2021 36 | 1 | 54, F | c-ANCA positive | Bilateral AOM and OME right mixed moderate-severe HL, left conductive mild HL, thickened tympanic membranes, vertigo, unilateral facial nerve palsy | Cortical mastoidectomy, steroids, cyclophosphamide, azathioprine | Partially improved | Partially improved (not specified) |

| Ratmeyer et al., 2021 37 | 1 | 72, F | c-ANCA positive | Right severe-profound sensorineural HL, left profound mixed HL | Glucocorticoids and cyclophosphamide | Minimally improved | Partially improved: at one month bilateral severe HL, with minimal improvement |

| Tokuyasu et al., 2022 38 | 1 | 78, F | c-ANCA positive | Right AOM, bilateral severe-profound SNHL | Prednisolone and cyclophosphamide | Improved | Improved: at 5 months, bilateral moderate SNHL |

| Koenen et al., 2022 39 | 1 | 29, M | c-ANCA positive | Bilateral AOM, right mixed HL, left sensorineural HL, unilateral facial nerve palsy | Bilateral ventilation tube, rituximab | Symptoms improved | Not reported |

| Tan et al., 2022 40 | 1 | 40, F | c-ANCA positive | Bilateral AOM | Right cortical mastoidectomy, left ventilation tube, prednisolone, methotrexate, and mycophenolate | Symptoms improved | Not reported |

| Nakamura et al., 2022 41 | 1 | 68, F | p-ANCA positive | Bilateral OMG, right tympanic perforation, bilateral severe mixed HL | Prednisone, right myringoplasty and CI | Improved | Persistent bilateral profound HL. Satisfactory audiological results after CI |

| Batinović et al., 2023 42 | 1 | 36, M | c-ANCA positive | Left AOM, facial palsy and severe mixed HL | Cyclophosphamide, methylprednisolone | Partially improved | Partially improved: at 6 months, moderate-severe |

| Murao et al., 2023 43 | 1 | 74, F | c-ANCA positive | Right OME, right deafness, left severe mixed HL | Prednisolone, methotrexate | Partially improved | Partially improved: left moderate-severe HL, right deafness |

| Satisfactory audiological results with hearing aids | |||||||

| Yoshida et al., 2023 44 | 2 | 64, F | Both p-ANCA positive | Bilateral OME, profound bilateral HL. | Pt 1 Prednisolone, cyclophosphamide, azathioprine, and left CI | Improved | Satisfactory audiological results after CI in both pts |

| 69, F | CT: | ||||||

| Pt 1, unilateral cochlear calcification | |||||||

| Pt 2, bilateral cochlear calcification (mild in left ear, worst in right one) | Pt 2 Prednisolone, cyclophosphamide, left CI | ||||||

| ANCA: anti-neutrophil cytoplasmic antibodies; c-ANCA: proteinase 3 ANCA; p-ANCA: myeloperoxidase ANCA; AOM: acute otitis media; F: female; HL: hearing loss; M: male; OME: otitis media with effusion; OMG: otitis media with granulation; SNHL: sensorineural hearing loss; CI: cochlear implant; PTA: pure tone audiometry; CWU: canal wall up. | |||||||

References

- Jennette J, Xiao H, Falk R. Pathogenesis of vascular inflammation by anti-neutrophil cytoplasmic antibodies. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2006;17:1235-1242. doi:https://doi.org/10.1681/ASN.2005101048

- McDonald T, DeRemee R. Wegener’s granulomatosis. Laryngoscope. 1983;93:220-231. doi:https://doi.org/10.1288/00005537-198302000-00020

- Wojciechowska J, KręCicki T. Clinical characteristics of patients with granulomatosis with polyangiitis and microscopic polyangiitis in ENT practice: a comparative analysis. Acta Otorhinolaryngol Ital. 2018;38:517-527. doi:https://doi.org/10.14639/0392-100X-1776

- Yoshida N, Hara M, Hasegawa M. Reversible cochlear function with ANCA-associated vasculitis initially diagnosed by otologic symptoms. Otol Neurotol. 2014;35:114-120. doi:https://doi.org/10.1097/MAO.0000000000000175

- Berrettini S, Ravecca F, Bruschini L. Progressive sensorineural hearing loss: immunologic etiology. Acta Otorhinolaryngol Ital. 1998;18:33-41.

- Takagi D, Nakamaru Y, Maguchi S. Otologic manifestations of Wegener’s granulomatosis. Laryngoscope. 2002;112:1684-1690. doi:https://doi.org/10.1097/00005537-200209000-00029

- Pagano M, Africano R, Lo Pinto G. Wegener granulomatosis: a clinical case with parossistic positional vertigo due to involvement of the lateral semicircular canal. Acta Otorhinolaryngol Ital. 1996;16:438-440.

- Ito Y, Shinogi J, Yuta A. Clinical records: a case report of Wegener’s granulomatosis limited to the ear. Auris Nasus Larynx. 1991;18:281-289. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/s0385-8146(12)80264-1

- Harabuchi Y, Kishibe K, Tateyama K. Clinical features and treatment outcomes of otitis media with antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibody (ANCA)-associated vasculitis (OMAAV): a retrospective analysis of 235 patients from a nationwide survey in Japan. Mod Rheumatol. 2017;27:87-94. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/14397595.2016.1177926

- Harabuchi Y, Kishibe K, Tateyama K. Clinical characteristics, the diagnostic criteria and management recommendation of otitis media with antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibody (ANCA)-associated vasculitis (OMAAV) proposed by Japan Otological Society. Auris Nasus Larynx. 2021;48:2-14. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.anl.2020.07.004

- Evren C, Tezer I. Endoscopic examination of the nasal cavity and nasopharynx in patients with otitis media. Kulak Burun Bogaz Ihtis Derg. 2013;1:100-106. doi:https://doi.org/10.5606/kbbu.2013.03521

- Hartl D, Aïdan P, Brugière O. Wegener’s granulomatosis presenting as a recurrence of chronic otitis media. Am J Otolaryngol. 1998;19:54-60. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/s0196-0709(98)90067-9

- Moussa A, Abou-Elhmd K. Wegener’s granulomatosis presenting as mastoiditis. Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol. 1998;107:560-563. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/000348949810700703

- Maguchi S, Fukuda S, Chida E. Myeloperoxidase-antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibody-associated sensorineural hearing loss. Auris Nasus Larynx. 2001;28:S103-S106. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/s0385-8146(00)00103-6

- Takagi D, Nakamaru Y, Maguchi S. Clinical features of bilateral progressive hearing loss associated with myeloperoxidase-antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibody. Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol. 2004;113:388-393. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/000348940411300509

- Ferri E, Armato E, Capuzzo P. Early diagnosis of Wegener’s granulomatosis presenting with bilateral facial paralysis and bilateral serous otitis media. Auris Nasus Larynx. 2007;34:379-382. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.anl.2007.01.005

- Yildirim N, Arslanoglu A, Aygun N. Otologic and leptomeningeal involvements as presenting features in seronegative Wegener granulomatosis. Am J Otolaryngol. 2008;29:147-149. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.amjoto.2007.04.007

- Yamazaki H, Fujiwara K, Shinohara S. Reversible cochlear disorders with normal vestibular functions in three cases with Wegener’s granulomatosis. Auris Nasus Larynx. 2012;39:236-240. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.anl.2011.03.010

- Wierzbicka M, Szyfter W, Puszczewicz M. Otologic symptoms as initial manifestation of Wegener granulomatosis: diagnostic dilemma. Otol Neurotol. 2011;32:996-1000. doi:https://doi.org/10.1097/MAO.0b013e31822558fd

- Sriskandarajah V, Bansal R, Yeoh R. Early intervention in localized Wegener’s granulomatosis with sensorineural hearing loss preserves hearing. Am J Audiol. 2012;21:121-126. doi:https://doi.org/10.1044/1059-0889(2012/12-0003)

- Lee J, Kim K, Myong N. Wegener’s granulomatosis presenting as bilateral otalgia with facial palsy: a case report. Korean J Audiol. 2013;17:35-37. doi:https://doi.org/10.7874/kja.2013.17.1.35

- Uppal P, Taitz J, Wainstein B. Refractory otitis media: an unusual presentation of childhood granulomatosis with polyangiitis. Pediatr Pulmonol. 2014;49:E21-E24. doi:https://doi.org/10.1002/ppul.22746

- Costa C, Polanski J. Wegener granulomatosis: otologic manifestation as first symptom. Int Arch Otorhinolaryngol. 2015;19:266-268. doi:https://doi.org/10.1055/s-0034-1387164

- Maniu A, Harabagiu O, Damian L. Mastoiditis and facial paralysis as initial manifestations of temporal bone systemic diseases - the significance of the histopathological examination. Rom J Morphol Embryol. 2016;57:243-248.

- Jeong S, Park J, Lee J. Progressive bilateral facial palsy as a manifestation of granulomatosis with polyangiitis: a case report. Ann Rehabil Med. 2016;40:734-740. doi:https://doi.org/10.5535/arm.2016.40.4.734

- Kim S, Jung A, Kim S. Refractory granulomatosis with polyangiitis presenting as facial paralysis and bilateral sudden deafness. J Audiol Otol. 2016;20:55-58. doi:https://doi.org/10.7874/jao.2016.20.1.55

- Brown P, Conlon N, Feighery C. Toothache and hearing loss: early symptoms of granulomatosis with polyangiitis (GPA). BMJ Case Rep. 2016;2016. doi:https://doi.org/10.1136/bcr-2016-214672

- Wawrzecka A, Szymańska A, Jeleniewicz R. Granulomatosis with polyangiitis with bilateral facial palsy and severe mixed hearing loss. Case Rep Otolaryngol. 2016;2016. doi:https://doi.org/10.1155/2016/5206170

- Elmas F, Shrestha B, Linder T. Subtotal petrosectomy and cochlear implant placement in otologic presentation of “Wegener’s granulomatosis.” Kathmandu Univ Med J (KUMJ). 2017;15:94-98.

- Kukushev G, Kalinova D, Sheytanov I. Two clinical cases of granulomatosis with polyangiitis with isolated otitis media and mastoiditis. Reumatologia. 2017;55:256-260. doi:https://doi.org/10.5114/reum.2017.71643

- Wang J, Leader B, Crane R. Granulomatosis with polyangiitis presenting as facial nerve palsy in a teenager. Int J Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol. 2018;107:160-163. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijporl.2018.02.009

- Mur T, Ghraib M, Khurana J. Granulomatosis with polyangiitis presenting with bilateral hearing loss and facial paresis. OTO Open. 2019;3. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/2473974X18818791

- Qaisar H, Shenouda M, Shariff M. Granulomatosis with polyangiitis manifesting as refractory otitis media and mastoiditis. Arch Iran Med. 2019;22:410-413.

- Marszał J, Bartochowska A, Yu R. Facial nerve paresis in the course of masked mastoiditis as a revelator of GPA. Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol. 2022;279:4271-4278. doi:https://doi.org/10.1007/s00405-021-07166-w

- Kousha A, Reed M, Else S. Isolated deafness as a presenting symptom in granulomatosis with polyangiitis. BMJ Case Rep. 2021;14. doi:https://doi.org/10.1136/bcr-2020-241159

- Djerić D, Perić A, Pavlović B. Otitis media with effusion as an initial manifestation of granulomatosis with polyangiitis. SAGE Open Med Case Rep. 2021;9. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/2050313X211036006

- Ratmeyer P, Johnson B, Roldan L. Granulomatosis with polyangiitis as a cause of sudden-onset bilateral sensorineural hearing loss: case report and recommendations for initial assessment. Case Rep Otolaryngol. 2021;2021. doi:https://doi.org/10.1155/2021/6632344

- Tokuyasu H, Hosoda S, Sueda Y. Granulomatosis with polyangiitis diagnosed during the treatment of otitis media with prednisolone in a patient with anti-neutrophil cytoplasmic antibody-associated vasculitis: a case report. Respir Med Case Rep. 2022;40. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rmcr.2022.101771

- Koenen L, Elbelt U, Olze H. Granulomatosis with polyangiitis in a patient with polydipsia, facial nerve paralysis, and severe otologic complaints: a case report and review of the literature. J Med Case Rep. 2022;16. doi:https://doi.org/10.1186/s13256-022-03492-7

- Tan I, Hashim N, Abdullah A. Quest in managing refractory mastoiditis – A case of granulomatosis with polyangiitis. JAMA Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2022;148:693-695. doi:https://doi.org/10.1001/jamaoto.2022.0835

- Nakamura T, Ganaha A, Tono T. Combined electric acoustic stimulation in a patient with otitis media with antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibody-associated vasculitis. Auris Nasus Larynx. 2022;49:1072-1077. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.anl.2021.04.009

- Batinović F, Martinić M, Durdov M. A case of unilateral otologic symptoms as initial manifestations of granulomatosis with polyangiitis. J Audiol Otol. 2023;27:161-167. doi:https://doi.org/10.7874/jao.2022.00311

- Murao Y, Yoshida Y, Oka N. Fluorodeoxyglucose-positron emission tomography/computed tomography-positive ear lesions responsive to immunosuppressive therapy in a patient with otitis media with antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibody-associated vasculitis. Mod Rheumatol Case Rep. 2023;7:134-137. doi:https://doi.org/10.1093/mrcr/rxac044

- Yoshida T, Kobayashi M, Sugimoto S. Labyrinthine calcification in ears with otitis media and antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibody-associated vasculitis (OMAAV): a report of two cases. Auris Nasus Larynx. 2023;50:299-304. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.anl.2022.01.004

- Tervaert J, Van Der Woude F, Fauci A. Association between active Wegener’s granulomatosis and anticytoplasmic antibodies. Arch Intern Med. 1989;149:2461-2465. doi:https://doi.org/10.1001/archinte.149.11.2461

- Nölle B, Specks U, Lüdemann J. Anticytoplasmic autoantibodies: their immunodiagnostic value in Wegener granulomatosis. Ann Intern Med. 1989;111:28-40. doi:https://doi.org/10.7326/0003-4819-111-1-28

- Brown K. Pulmonary vasculitis. Proc Am Thorac Soc. 2006;3:48-57. doi:https://doi.org/10.1513/pats.200511-120JH(2006)

- Thornton M, O’Sullivan T. Otological Wegener’s granulomatosis: a diagnostic dilemma. Clin Otolaryngol Allied Sci. 2000;25:433-434. doi:https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1365-2273.2000.00335.x

- Morita S, Nakamaru Y, Nakazawa D. Elevated level of myeloperoxidase-deoxyribonucleic acid complex in the middle ear fluid obtained from patients with otitis media associated with antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibody-associated vasculitis. Otol Neurotol. 2018;39:E257-E262. doi:https://doi.org/10.1097/MAO.0000000000001708

- Morita S, Nakamaru Y, Nakazawa D. The diagnostic and clinical utility of the myeloperoxidase-DNA complex as a biomarker in otitis media with antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibody-associated vasculitis. Otol Neurotol. 2019;40:E99-E106. doi:https://doi.org/10.1097/MAO.0000000000002081

- Beltrán Rodríguez-Cabo O, Reyes E, Rojas-Serrano J. Increased histopathological yield for granulomatosis with polyangiitis based on nasal endoscopy of suspected active lesions. Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol. 2018;275:425-429. doi:https://doi.org/10.1007/s00405-017-4841-z

- Stegeman C, Tervaert J, Sluiter W. Association of chronic nasal carriage of Staphylococcus aureus and higher relapse rates in Wegener granulomatosis. Ann Intern Med. 1994;120:12-17. doi:https://doi.org/10.7326/0003-4819-120-1-199401010-00003

- Tadema H, Heeringa P, Kallenberg C. Bacterial infections in Wegener’s granulomatosis: mechanisms potentially involved in autoimmune pathogenesis. Curr Opin Rheumatol. 2011;23:366-371. doi:https://doi.org/10.1097/BOR.0b013e328346c332

- Ohtani I, Baba Y, Suzuki C. Temporal bone pathology in Wegener’s granulomatosis. Fukushima J Med Sci. 2000;46:31-39. doi:https://doi.org/10.5387/fms.46.31

- Kornblut A, Wolff S, Fauci A. Ear disease in patients with Wegener’s granulomatosis. Laryngoscope. 1982;92:713-717. doi:https://doi.org/10.1288/00005537-198207000-00001

- Nakamaru Y, Takagi D, Oridate N. Otolaryngologic manifestations of antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibody-associated vasculitis. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2012;146:119-121. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/0194599811424044

- Morita Y, Takahashi K, Izumi S. Vestibular involvement in patients with otitis media with antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibody-associated vasculitis. Otol Neurotol. 2017;38:97-101. doi:https://doi.org/10.1097/MAO.0000000000001223

- Nicklasson B, Stangeland N. Wegener’s granulomatosis presenting as otitis media. J Laryngol Otol. 1982;96:277-280. doi:https://doi.org/10.1017/s0022215100092501

- D’Anza B, Langford C, Sindwani R. Sinonasal imaging findings in granulomatosis with polyangiitis (Wegener granulomatosis): a systematic review. Am J Rhinol Allergy. 2017;31:16-21. doi:https://doi.org/10.2500/ajra.2017.31.4408

- Sanders J, Huitma M, Kallenberg C. Prediction of relapses in PR3-ANCA-associated vasculitis by assessing responses of ANCA titres to treatment. Rheumatology (Oxford). 2006;45:724-729. doi:https://doi.org/10.1093/rheumatology/kei272

- Holle J, Gross W, Holl-Ulrich K. Prospective long-term follow-up of patients with localised Wegener’s granulomatosis: does it occur as persistent disease stage?. Ann Rheum Dis. 2010;69:1934-1939. doi:https://doi.org/10.1136/ard.2010.130203

- Okada M, Suemori K, Takagi D. Comparison of localized and systemic otitis media with ANCA-associated vasculitis. Otol Neurotol. 2017;38:E506-E510. doi:https://doi.org/10.1097/MAO.0000000000001563

- Okada M, Suemori K, Takagi D. The treatment outcomes of rituximab for intractable otitis media with ANCA-associated vasculitis. Auris Nasus Larynx. 2019;46:38-42. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.anl.2018.05.011

- Yates M, Watts R, Bajema I. EULAR/ERA-EDTA recommendations for the management of ANCA-associated vasculitis. Ann Rheum Dis. 2016;75:1583-1594. doi:https://doi.org/10.1136/annrheumdis-2016-209133

- Iwata S, Okada M, Suemori K. The hearing prognosis of otitis media with ANCA-associated vasculitis. Auris Nasus Larynx. 2021;48:377-382. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.anl.2020.09.004

- Tabei A, Sakairi T, Ohishi Y. Otitis media with ANCA-associated vasculitis: a retrospective study of 30 patients. Mod Rheumatol. 2022;32:923-929. doi:https://doi.org/10.1093/mr/roab078

- Watanabe T, Yoshida H, Kishibe K. Cochlear implantation in patients with bilateral deafness caused by otitis media with ANCA-associated vasculitis (OMAAV): a report of four cases. Auris Nasus Larynx. 2018;45:922-928. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.anl.2017.12.007

Downloads

License

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

Copyright

Copyright (c) 2025 Società Italiana di Otorinolaringoiatria e chirurgia cervico facciale

How to Cite

- Abstract viewed - 1426 times

- PDF downloaded - 215 times