Audiology

Vol. 45: Issue 4 - August 2025

Preliminary evaluation and reliability of the Italian adaptation of the dichotic digit test in adults and children

Abstract

Background. Dichotic listening tests, such as the Dichotic Digit Test (DDT) developed by F. Musiek, are vital for assessing auditory processing disorders. There is a lack of validated auditory tests in Italian, necessitating the adaptation of existing tools.

Objective. This study aims to provide a preliminary assessment of the reliability and normative data for the newly adapted Italian version of the DDT. It hypothesises that the Italian DDT will show comparable reliability and normative data to the original English version, with a similar Right-Ear Advantage (REA).

Methods. The adaptation process involved a pilot study with 20 normal hearing adults, comparing the English and Italian versions of the DDT. Subsequently, the study included 138 children aged 6-10 years, using the Italian version to assess test-retest reliability and gather normative data.

Results. The findings revealed a consistent REA across participants that was more pronounced in younger children. The Italian version of DDT demonstrated adequate reliability across age groups and gender, with test-retest stability observed in both adults and children.

Conclusions. This preliminary study provides essential data on the reliability and normative scores of the Italian DDT. The findings support its use in clinical and research settings, although further studies are required for comprehensive validation.

Introduction

Dichotic hearing is the ability of the listener to process different information being presented to each ear at the same time. Individuals with difficulties in binaural integration often show a significant ear deficit, usually the left ear, and may have difficulty hearing in background noise or when more than one person is speaking 1. The role of dichotic listening in cognitive neuroscience is particularly crucial, offering valuable insights into the complexities of auditory processing and hemispheric asymmetry 2-4. Tracing back the origins of dichotic listening tests reveal the pioneering efforts of Broadbent and Kimura, who laid the groundwork for understanding auditory perception through dichotic techniques 5,6.

The evolution of these tests saw a significant milestone with the introduction of the Dichotic Digit Test (DDT) by Musiek 7. Unlike earlier auditory tests, which often focused on simple auditory detection or discrimination tasks, Musiek’s DDT added a layer of complexity by simultaneously presenting pairs of different digits to each ear into a quick and reliable test. These technical aspects of the DDT, from the nature of auditory messages to the interpretation of results, were crucial for its successful application and have contributed significantly to cognitive and language research 8,9. Therefore, the DDT is particularly effective in identifying a range of brain and brainstem pathologies, underscoring its utility in clinical settings 7. Furthermore, the use of digits enhanced the test’s sensitivity in the diagnosis of central Auditory Processing Disorders (cAPD), allowing a more precise identification of binaural integration deficits. Consequently, the DDT has become an essential instrument in diagnosis of cAPD, providing critical insights into how individuals process complex auditory information. This advancement represented a leap forward in auditory processing research, allowing for more nuanced and precise assessments of how the brain interprets and processes auditory signals 7,10.

Although the DDT has been extensively adapted and used in many different languages, demonstrating its robustness in measuring cAPD across different countries, in Italy there is a general lack of test for cAPD and the DDT is also not available in the Italian language, leaving a significant gap in both clinical diagnostics and auditory research. Moreover, the lack of normative data for the Italian-speaking population limits the ability to compare results across different linguistic and cultural groups, hindering comprehensive auditory research 8,11. The adaptation process of the DDT in Italian was not merely a translation of the test, but a comprehensive adaptation that ensured the test’s reliability and validity within the Italian linguistic framework 1,12. According to previous Italian studies on dichotic listening 13, such modifications are essential in extending the reach and applicability of DDT, allowing for more inclusive and representative auditory processing research 14 but also not to overlook the importance of linguistic and cultural considerations in psychological assessments.

This study aimed to develop and preliminarily assess the reliability and normative data of the Italian version of the DDT. It sought to evaluate the test’s reliability, specifically focusing on the consistency of results across different age groups and the presence of a Right-Ear Advantage (REA). It is hypothesised that the Italian DDT will demonstrate reliability comparable to the original English version, with similar normative data and a consistent REA pattern across various age groups.

Materials and methods

Test administration and calibration

A 2-channel audiometre with separately calibrated channels was used. As indicated in the literature 7, the DDT is optimal starting from 20 dB SL from the audibility threshold at 1000 Hz and is generally presented at 50 dB SL. Therefore, DDT was proposed at 50 dB SL in both the experiments, and intensity was maintained equally in each ear.

Instructions to the patient were as follows: “You will hear 2 numbers in each ear. Please listen carefully and repeat all the numbers you hear, in any order. Guessing is better than omitting a response if you are unsure”. The first few trials served as practice and were not included in the scoring. The test, consisting of 20 dichotic pairs, was administered with the patient given ample time to respond. Between each pair of numbers there is 4 seconds of pause in which time the patient can answer. The DDT’s design facilitated easy administration and scoring, suitable for a broad patient range, including those with hearing loss and it takes only up to 2 minutes to be completed, at any age.

To ensure test standardisation, a quiet environment in a soundproof booth, free of acoustic and visual stimuli, according to the UNI EN ISO 8253-3:2022, was maintained in all tests.

DDT adaptation to the Italian language

To ensure the validity of the DDT in its Italian adaptation, we firstly recorded the original list of numbers from the English-language DDT by Musiek 7 (Tab. I). This involved recording digit sequences in the Italian language, with a particular focus on maintaining consistent phonetic lengths and the same attack time of the voice within 30 msec, maintaining intact the procedure of execution of the test 1,7,15. The critical adjustment in the Italian version consisted in deleting the digit ‘three’ in all pairs to rectify phonetic imbalances, as its pronunciation in Italian significantly differs from the other digits and with a different length that did not allow the post recording digital stretch of this number.

On the other hand, in the English version “seven” had been deleted since it was too long, but it was reintroduced in the final Italian version (Italian DDT) (Tab. II).

The digit pairs selected for the Italian version are illustrated in Table III, culminating in a total of 20 couples of digits (single DDT) and 20 couples of 2 distinct pairs of digits (4 numbers) presented simultaneously in each ear. The creation of the new Italian DDT was accomplished using the digital audio workstation, “FL Studio”. During this process, meticulous adjustments were made to ensure equal intensity levels across the digit pairs and to standardise the duration of each digit (fixed durations, equals of all the digits, as in the English-language DDT).

The speaker was a professional Italian native speaker (male, 58 years old). The recording length of each digit was respectively: “1” 438 msec, “2” 429 msec, “3” 272 msec, “4” 557 msec, “5” 548 msec, “6” 700 msec, “7” 638 msec, “8” 726 msec, “9” 539 msec and “10” 618 msec. After the post-recording digital processing, in the adapted Italian version of DTT, the length of each digit was 700 ± 0.10 msec. Each pair of double digits lasts 8 seconds, with a pause of 4 seconds among the double digits.

Study sample and design

The initial study sample comprised 20 normal hearing subjects (10 females, 10 males; mean age, 24.4 ± 7.7 years old), ranging from 19 to 53 years with a documented normal pure-tone threshold within 20 dB HL at all frequencies from 250 to 8000 Hz, without conductive or sensorineural hearing deficit, and negative for neurological diseases or prior or actual ear pathologies or ear surgery.

This group underwent testing with the original English (Auditek, St. Louis, Missouri USA) and the Italian versions of DDT: 2 versions of the Italian DDT – the direct translation of the Musiek’s DDT (translated) and the adapted version (Italian DDT) – were used for testing. A comparative study was then conducted using the original English and the Italian versions. The Italian DDT version has been retested after 1 month in order to assess test-retest variability, becoming the final version of Italian DDT for the second experiment with children.

A second experiment involved 240 normal hearing children aged from 6 to 10 years (105 females, 135 males; mean age, 7.2 ± 0.8), from 4 different schools (Bresso and Lodi, Lombardy, Italy). The gender distribution was balanced across the schools. This sample was randomly recruited. Written informed consent was obtained from both parents and anonymity has been guaranteed.

A parental report of clinical history was conducted to exclude cognitive problems, learning or language disorders, past speech therapy, or language delay or other clinical issues that might have caused an altered result 16. The Screening Instrument for Targeting Educational Risk (SIFTER) questionnaire was given to their teachers to evaluate school performance 17.

All the children except 9, who were not available in the days of testing, underwent otoscopy, pure-tone audiometry, immittance audiometry and were tested with the previously studied adapted version of the Italian DDT (Italian DDT). All children were able to perform the DDT and completed the evaluation.

Inclusion criteria were the willingness to participate to the study, assessed orally, and age from 6 to 10 years. All clinical history records were analysed by a trained specialised physician who also performed otoscopies prior to audiometric testing. Exclusion criteria were: external, middle and/or inner ear malformations, ear pathologies revealed by clinical history and/or otoscopy and/or abnormal hearing findings, sensorineural hearing loss, clinical history positive for neuropsychological disorders (non-verbal IQ < 80%, phonological processing and/or attention skills disorders) and/or cognitive impairments, reported delayed language development by the parents, non-native Italian language speaking and reported difficulties at school by teachers and/or parents. A possible or documented central auditory processing disorders reported by the teachers and/or the family was a criterion for exclusion.

The study included 138 children (68 males, 70 females), as a normal reference, ranging from 6 to 10 years (mean age: 8.0 ± 0.5 years), whose DDT results were analysed.

Statistical analysis

All statistics were calculated with the Statistical Package for the Social Sciences 26 for Windows software package (SPSS Inc, Chicago, Illinois). The Shapiro-Wilk normality test was first applied to the dataset to assess the normality of continuous variables. A Wilcoxon rank-signed exact test (2-tailed) was used to assess differences between the results. Values were considered statistically significant when p < 0.05.

A 2-way random intraclass correlation coefficient (ICC) was assessed, between 0 and 1, where values below 0.5 indicate poor reliability, between 0.5 and 0.75 moderate reliability, between 0.75 and 0.9 good reliability, and any value above 0.9 indicates excellent reliability.

Results

Experiment 1

TEST DEVELOPMENT AND ADAPTATION

The initial comparison between the English and Italian versions of the DDT revealed a notably better performance with the tests using a mere translation from English to Italian of the DDT. This improvement is primarily attributed to the participants’ native language (Italian) proficiency, compared to the result in the English language. The comparative ease of native language utilisation over a non-native one, notably English in this study, emerges as a significant determinant in test performance.

Interestingly, both the English and Italian versions demonstrated similar performance in single ear tests (both right and left ears), suggesting a baseline equivalence in auditory processing across languages. However, significant differences were observed in the double version tests compared to the single ones, showing a p value of 0.002 in the left ear and a p value of 0.012 in the right ear (Tab. IV). These findings indicate a more profound involvement of central auditory processes when conducting the test in a bilingual context.

ITALIAN DDT ASSESSMENT

The comparison between the translated and Italian DDT version revealed minimal but non-significant differences (p = ns). As assessed in the mother language, no difference was observed between the single and double DDT with both versions (p=ns) thus emphasising the DDT’s focus on central rather than peripheral auditory pathways (Tab. II). The Italian version, selected for its optimised dichotic attributes, ensured unbiased results that were free from pre-voicing or a lag-effect, with simultaneous different messages in intensity and phase 1.

Therefore, due to the lack of statistical difference between the 2 versions, the Italian DDT was considered suitable to be chosen as the final Italian version of DDT and used in the second experiment of this study.

The Italian DDT version was retested after 1 month in all 20 already tested normal subjects. The test-retest reproducibility of the final Italian version, evaluated through the ICC calculated as the intra-subject variance on the total variance, was 0.89.

Experiment 2

PARTICIPANT DEMOGRAPHICS AND DATA

The children cooperated effectively, showing appreciation and curiosity towards the research activity, with none refusing to participate or requiring special reminders to maintain attention. Despite some variability in tympanogram results, all data were considered for analysis, as peripheral conductive auditory factors did not significantly impact the DDT outcomes (Fig. 1). Exploratory analysis of hand preference revealed minimal impact on DDT outcomes, except in the 7-year age group in the double DDT (p = 0.01).

RESULTS OF DDT MEASUREMENT IN CHILDREN

As seen in Table V, better scores were generally observed on the right side across all age groups in the single DDT, with scores consistently above 90 (Tab. V). In younger age groups, specifically ages 6 to 8 years, there was a clear pattern of REA. For instance, 6-year-old children exhibited a mean right ear score of 90.71, compared to 79.29 for the left ear, with a statistically significant ear advantage of 11.43 (p value: 0.02). This trend persisted in 7-year-old children, who demonstrated a mean right ear score of 93.98 vs 89.17 for the left ear, and an ear advantage of 4.81, with a highly significant p value of 0.002. The 8-year-old children continued this trend with a reduced right ear advantage (mean scores of 94.3 for the right ear and 90.94 for the left ear, ear advantage of 3.40, p value of 0.024). However, as the participants aged, this pattern showed a notable shift. The 9-year-old children, despite achieving high mean scores (100.00 for the right ear and 95.00 for the left ear), did not exhibit a statistically significant ear advantage (p value: ns), indicating a decrease in the pronounced right ear dominance observed in younger children. This trend became more apparent in the 10-year-old group, where, for the first time, a reversal was observed with a mean score of 90.00 for the right ear and 95.00 for the left ear, resulting in an ear advantage of -5.00 favouring the left ear, although this difference was not statistically significant (p value: ns). Results were compared in the table with the average rates of Malay language adaptation 18. The findings suggest a developmental trajectory in auditory processing, with a pronounced right ear (or left hemisphere) dominance in early childhood that gradually diminishes with age. This diminishing REA and the emerging left ear dominance in older children (9 and 10 years) may indicate a developmental shift towards more balanced or bilateral auditory processing.

The double DDT also revealed a pronounced REA, particularly in younger participants (Fig. 1). This dominance lessened with age, as shown by converging scores in both ears. The ear advantage was most significant in the 6- to 7-year age group, diminishing in older children.

Discussion

This study confirms that the Italian DDT was easily administered in under 5 minutes and is quickly scored, with a slightly linguistically loaded, closed-response set, easily understood by children with instructions that is not needed to be repeated, and relatively resistant to at least mild conductive or sensorineural hearing loss and also adaptable with children.

The comprehensive comparison between the original English version and both the Italian versions underscored more pronounced differences than initially supposed, confirming that the DDT’s primary focus is on evaluating central auditory processes, which include elements of foreign language processing. This enhanced contrast between the double DDT and single was observed only when the original English test was proposed to the normal hearing Italian speaking group. This highlights the robustness of the DDT in assessing core auditory functions across different linguistic contexts. The negligible variance between the 2 versions supports the DDT’s effectiveness across languages, affirming its reliability irrespective of phonetic composition. In any case, the high level of reproducibility underscores the reliability of the DDT over multiple administrations, thereby affirming its applicability in both clinical and research contexts. The comparison of the 2 Italian DDTs corroborates the test’s central auditory focus, which is unaffected by phonetic differences. However, the selection of the second adapted version into the Italian language was chosen for its optimal dichotic qualities, mitigating the risks of pre-voicing and a lag effect. Based on previous studies in the literature, not guaranteeing the perfect alignment of dichotic listening causes a higher identification of numbers. Furthermore, there is a disparity within the pairs of the list that ensures a less accurate result at retesting 1,15.

This consistent REA, observed across a diverse demographic range, confirms the test’s reliability and applicability within the Italian-speaking population. As reported by Kimura et al. 5, the fact that the right ear has a slight advantage on dichotic listening tasks, compared with the left ear, is based on the anatomical model of auditory processing, due to left brain hemispheric dominance for language, which receives direct auditory input from the right ear (i.e., strong contralateral auditory pathway). As expected, our data confirmed this important issue also with the Italian DDT within the normal hearing subject group that was also confirmed at test-retest evaluation. Furthermore, also in experiment 2, a consistent REA in both single and double DDT tasks was observed, aligning with established dichotic listening patterns which were comparable to Musiek’s results in the English language 7.

Comparison of DDT adaptations across languages

The DDT has been adapted into several languages, including French 19, Spanish 20, Polish 21, Malay 18, Norwegian 22, and Dutch 23, as well as for low and middle income countries 24.

Age effects, not extensively explored in Musiek’s original work 7, have been a significant focus in subsequent adaptations. All studies found significant age-related improvements in DDT performance. Notably, the Malay adaptation by Mukari et al. 18 tested children as young as 6 years, finding results comparable to our adaptation. For instance, in the double DDT, 6-year-old children in the Malay study scored 83.3% (SD 11.8) for the right ear and 69.6% (SD 14) for the left ear, closely aligning with our findings of 83.3% (SD 7.6) for the right ear and 55.8% (SD 32.2) for the left ear. This consistency across languages supports the DDT’s validity as a measure of auditory processing development.

A consistent REA was observed across all adaptations, aligning with Musiek’s original findings. However, the magnitude of this advantage varied across studies. Mukari et al. 18 reported a larger REA (13-15% in younger children) in the Malay adaptation, while Neijenhuis et al. 23 found a more modest REA (about 10% across ages) in the Dutch version.

All adaptations maintained a quick administration time, as established in Musiek’s original version 7. This brevity, combined with the absence of floor or ceiling effects, underscores the DDT’s efficiency as a clinical tool across different linguistic contexts.

All studies concur that the double DDT is more appropriate for clinical use compared to the single DDT. The French adaptation even employs a triple DDT with 3 digits in the same ear, further increasing task complexity. This consensus highlights the test’s ability to challenge the auditory system sufficiently without inducing floor or ceiling effects, a crucial factor in its clinical utility.

High test-retest reliability was consistently reported across adaptations, supporting Musiek’s original assertion of the DDT’s clinical utility 7. The Malay 18 and Dutch 23 versions reported high reliability, consistent with the original English version. Our version reported an intraclass correlation coefficient comparable to the high reliability noted in other adaptations.

REA observations and age-related findings

The single DDT showed a marginal right-left ear disparity, with the right ear generally scoring higher. The double DDT showed a more pronounced right ear dominance, which was especially evident in younger participants. This pattern suggests that right ear dominance documented by the REA lessens with age, mirroring the maturation of the cerebral hemispheres. This maturation process reaches a stage akin to adults, particularly after 8 years of age 6,25,26. A significant REA was also noted in the 6 to 7-year age group, with this trend diminishing in older children. However, 6-year-old subjects presented a lager variability, also confirming in the Italian language the observation reported by Musiek et al. 6 that the DDT is more reliable from the age of 7 years.

Methodological approach and limitations

The methodological design prioritised simplicity and replicability, enhancing the potential for widespread application of the Italian DDT. This approach, alongside the structured protocol and careful selection of the lists, underlines the test’s practical utility. However, the study has limitations due to variable sample homogeneity. Future works addressing this aspect could further solidify the DDT’s clinical relevance. It is noteworthy that the non-significance of certain multivariate analysis parameters may stem from the variables’ heterogeneous nature. Despite these limitations, the diverse analyses conducted provided valuable insights from multiple perspectives. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first adaptation that considers tympanometry in relation to dichotic listening evaluation. These measures were included because chronic catarrhal conditions are known to affect both attention and this type of auditory processing 27,28.

The Italian DDT holds substantial promise for clinical audiology, particularly as an early detection tool for auditory processing disorders. Its utility extends to educational settings, aiding in crafting tailored educational approaches for children with atypical auditory lateralisation 29,30. The successful adaptation of the DDT for Italian speakers marks a significant stride in auditory and cognitive research domains. A future study could expand on this by conducting the test using the Speech-in-Noise test to determine if there is a correlation, and by including a group of children with cAPD. The reaffirmation of the DDT’s efficacy as a measure of auditory processing in this study also serves to enrich the discourse on lateralised auditory processing 31-33. This preliminary report introducing the DDT in Italian may pave the way for its use in larger, more comprehensive studies.

Conclusions

The successful adaptation and validation of the DDT for the Italian-speaking population represents a significant advancement in auditory processing research. As a valid, efficient, and easily administered tool, the Italian DDT excels in detecting cAPD-related disturbances in both adults and children. Its addition to the multilingual repertoire of DDTs underscores its global relevance in assessing auditory processing asymmetries, especially REA, and is pivotal in understanding auditory processing variations in diverse populations.

Establishing normative data for the Italian DDT is a remarkable achievement that confirms the previously suggested normality ranges, extending the test’s utility across different age groups. Its minimal linguistic bias enhances its suitability for educational and clinical applications, particularly with younger patients. The Italian DDT’s ease of use and reproducibility positions it as a crucial component in the array of diagnostic tools for central auditory processing disorders.

Looking forward, the Italian DDT’s potential in broader clinical applications, including longitudinal studies, is vast. It may help to shed light on the evolution of auditory processing abilities, offering vital insights for developmental and degenerative auditory processing. Such insights are instrumental in shaping educational methods and therapeutic interventions. Thus, the Italian DDT emerges as a key element in auditory neuropsychology, heralding new research and clinical pathways in the realm of auditory processing.

Acknowledgements

Special thanks are due to Sarah Mastrillo and Giulia Visconti for their contribution to the data collection process and their dedicated efforts during their bachelor’s degree thesis and to Matteo Rullo for helping in the digital recording postprocessing sound modifications. The authors also acknowledge the Croce Rossa Italiana, Dr. Arturo Zaghis, Arch. Michela Vimercati (Sali’s family), the Lions of Lodi for the authorizations’ access to the school and the participants and the teachers for their patience and cooperation. The authors are grateful to Prof. Alessandro Martini, Dr. Daniela Ginocchio and Prof. Frank Musiek for their advice.

Conflict of interest statement

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Funding

The research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Author contributions

MG: wrote the manuscript; LB: made the statistical analysis; NM: reviewed the literature; VC, EF: provided and superivised data collection; LP, DZ: reviewed the final version, supervised the work: FDB: wrote the draft manuscript, conceptualized the work, performed data collection and data analysis supervision.

Ethical consideration

This study was approved by the Institutional Ethics Committee of Fondazione IRCCS Ca’ Granda Ospedale Maggiore Policlinico of Milan, Italy (IRB 455_2017). The research was conducted ethically, with all study procedures being performed in accordance with the requirements of the World Medical Association’s Declaration of Helsinki. Written informed consent was obtained from each participant and parents’ partecipants for study participation and data publication. Patients’ anonymity has been guaranteed.

History

Received: February 18, 2024

Accepted: December 15, 2024

Figures and tables

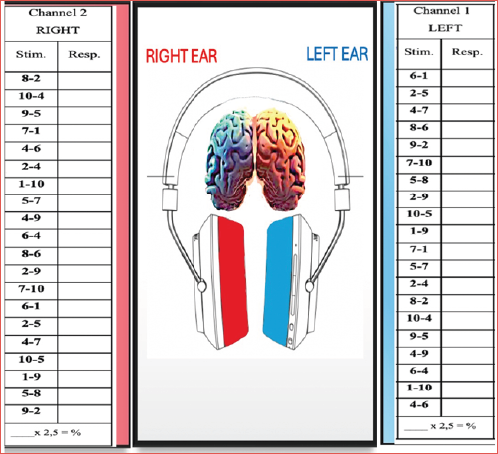

Figure 1. REA is observed across all age groups, especially in younger participants, diminishing with age.

| Musiek’s “translated”single | Channel 1 | Channel 2 | Musiek’s “translated” | Channel 1 | Channel 2 | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| DDT | LEFT | RIGHT | Double DDT | LEFT | RIGHT | ||||

| TRIAL # | Stim. | Trans. | Stim. | Trans. | TRIAL # | Stim. | Trans. | Stim. | Trans. |

| 1 | 1 | /ˈuːno/ | 7 | /ˈsεtːe/ | 1 | 6-1 | /ˈsεi/-/ˈuːno/ | 8-2 | /ˈotːo/-/ˈdue/ |

| 2 | 8 | /ˈotːo/ | 3 | /ˈtrε/ | 2 | 2-5 | /ˈdue/-/ˈtʃiŋkwe/ | 10-4 | /ˈdiεtʃi/-/ˈkwatːro/ |

| 3 | 2 | /ˈdue/ | 6 | /ˈsεi/ | 3 | 4-3 | /ˈkwatːro/-/ˈtrε/ | 9-5 | /ˈnɔve/-/ˈtʃiŋkwe/ |

| 4 | 3 | /ˈtrε/ | 4 | /ˈkwatːro/ | 4 | 8-6 | /ˈotːo/-/ˈsεi/ | 3-1 | /ˈtrε/-/ˈuːno/ |

| 5 | 1 | /ˈuːno/ | 3 | /ˈtrε/ | 5 | 9-2 | /ˈnɔve/-/ˈdue/ | 4-6 | /ˈkwatːro/ |

| -/ˈsεi/ | |||||||||

| 6 | 7 | /ˈsεtːe/ | 5 | /ˈtʃiŋkwe/ | 6 | 3-10 | /ˈtrε/-/ˈdiεtʃi/ | 2-4 | /ˈdue/-/ˈkwatːro/ |

| 7 | 5 | /ˈtʃiŋkwe/ | 3 | /ˈtrε/ | 7 | 5-8 | /ˈtʃiŋkwe/-/ˈotːo/ | 1-10 | /ˈuːno/-/ˈdiεtʃi/ |

| 8 | 1 | /ˈuːno/ | 2 | /ˈdue/ | 8 | 2-9 | /ˈdue/-/ˈnɔve/ | 5-3 | /ˈtʃiŋkwe/-/ˈtrε/ |

| 9 | 3 | /ˈtrε/ | 10 | /ˈdiεtʃi/ | 9 | 10-5 | /ˈdiεtʃi/-/ˈtʃiŋkwe/ | 4-9 | /ˈkwatːro/-/ˈnɔve/ |

| 10 | 6 | /ˈsεi/ | 2 | /ˈdue/ | 10 | 1-9 | /ˈuːno/-/ˈnɔve/ | 6-4 | /ˈsεi/- |

| /ˈkwatːro/ | |||||||||

| 11 | 10 | /ˈdiεtʃi/ | 7 | /ˈsεtːe/ | 11 | 7-1 | /ˈsεtːe/-/ˈuːno/ | 8-6 | /ˈotːo/-/ˈsεi/ |

| 12 | 4 | /ˈkwatːro/ | 9 | /ˈnɔve/ | 12 | 5-7 | /ˈtʃiŋkwe/-/ˈsεtːe/ | 2-9 | /ˈdue/-/ˈnɔve/ |

| 13 | 8 | /ˈotːo/ | 1 | /ˈuːno/ | 13 | 2-4 | /ˈdue/-/ˈkwatːro/ | 7-10 | /ˈsεtːe/-/ˈdiεtʃi/ |

| 14 | 7 | /ˈsεtːe/ | 5 | /ˈtʃiŋkwe/ | 14 | 8-2 | /ˈotːo/-/ˈdue/ | 6-1 | /ˈsεi/-/ˈuːno/ |

| 15 | 8 | /ˈotːo/ | 10 | /ˈdiεtʃi/ | 15 | 10-4 | /ˈdiεtʃi/-/ˈkwatːro/ | 2-5 | /ˈdue/-/ˈtʃiŋkwe/ |

| 16 | 6 | /ˈsεi/ | 2 | /ˈdue/ | 16 | 9-5 | /ˈnɔve/-/ˈtʃiŋkwe/ | 4-7 | /ˈkwatːro/-/ˈsεtːe/ |

| 17 | 9 | /ˈnɔve/ | 4 | /ˈkwatːro/ | 17 | 4-9 | /ˈkwatːro/-/ˈnɔve/ | 10-5 | /ˈdiεtʃi/-/ˈtʃiŋkwe/ |

| 18 | 1 | /ˈuːno/ | 9 | /ˈnɔve/ | 18 | 6-4 | /ˈsεi/-/ˈkwatːro/ | 1-9 | /ˈuːno/-/ˈnɔve/ |

| 19 | 2 | /ˈdue/ | 8 | /ˈotːo/ | 19 | 1-10 | /ˈuːno/-/ˈdiεtʃi/ | 5-8 | /ˈtʃiŋkwe/-/ˈotːo/ |

| 20 | 10 | /ˈdiεtʃi/ | 7 | /ˈsεtːe/ | 20 | 4-6 | /ˈkwatːro/-/ˈsεi/ | 9-2 | /ˈnɔve/-/ˈdue/ |

| Italian single | Channel 1 | Channel 2 | Italian double | Channel 1 | Channel 2 | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| DDT | LEFT | RIGHT | DDT | LEFT | RIGHT | ||||

| TRIAL # | Stim. | Trans. | Stim. | Trans. | TRIAL # | Stim. | Trans. | Stim. | Trans. |

| 1 | 1 | /ˈuːno/ | 7 | /ˈsεtːe/ | 1 | 6-1 | /ˈsεi/-/ˈuːno/ | 8-2 | /ˈotːo/-/ˈdue/ |

| 2 | 8 | /ˈotːo/ | 4 | /ˈkwatːro/ | 2 | 2-5 | /ˈdue/-/ˈtʃiŋkwe/ | 10-4 | /ˈdiεtʃi/-/ˈkwatːro/ |

| 3 | 2 | /ˈdue/ | 6 | /ˈsεi/ | 3 | 4-7 | /ˈkwatːro/-/ˈsεtːe/ | 9-5 | /ˈnɔve/-/ˈtʃiŋkwe/ |

| 4 | 7 | /ˈsεtːe/ | 4 | /ˈkwatːro/ | 4 | 8-6 | /ˈotːo/-/ˈsεi/ | 7-1 | /ˈsεtːe/-/ˈuːno/ |

| 5 | 1 | /ˈuːno/ | 9 | /ˈnɔve/ | 5 | 9-2 | /ˈnɔve/-/ˈdue/ | 4-6 | /ˈkwatːro/-/ˈsεi/ |

| 6 | 7 | /ˈsεtːe/ | 5 | /ˈtʃiŋkwe/ | 6 | 7-10 | /ˈsεtːe/-/ˈdiεtʃi/ | 2-4 | /ˈdue/-/ˈkwatːro/ |

| 7 | 5 | /ˈtʃiŋkwe/ | 8 | /ˈotːo/ | 7 | 5-8 | /ˈtʃiŋkwe/-/ˈotːo/ | 1-10 | /ˈuːno/-/ˈdiεtʃi/ |

| 8 | 1 | /ˈuːno/ | 2 | /ˈdue/ | 8 | 2-9 | /ˈdue/-/ˈnɔve/ | 5-7 | /ˈtʃiŋkwe/-/ˈsεtːe/ |

| 9 | 7 | /ˈsεtːe/ | 10 | /ˈdiεtʃi/ | 9 | 10-5 | /ˈdiεtʃi/-/ˈtʃiŋkwe/ | 4-9 | /ˈkwatːro/-/ˈnɔve/ |

| 10 | 10 | /ˈdiεtʃi/ | 7 | /ˈsεtːe/ | 10 | 1-9 | /ˈsεtːe/-/ˈuːno/ | 6-4 | /ˈotːo/-/ˈsεi/ |

| 11 | 6 | /ˈsεi/ | 2 | /ˈdue/ | 11 | 3-1 | /ˈuːno/-/ˈnɔve/ | 8-6 | /ˈsεi/-/ˈkwatːro/ |

| 12 | 4 | /ˈkwatːro/ | 9 | /ˈnɔve/ | 12 | 5-3 | /ˈtʃiŋkwe/-/ˈsεtːe/ | 2-9 | /ˈdue/-/ˈnɔve/ |

| 13 | 8 | /ˈotːo/ | 1 | /ˈuːno/ | 13 | 2-4 | /ˈdue/-/ˈkwatːro/ | 3-10 | /ˈsεtːe/-/ˈdiεtʃi/ |

| 14 | 3 | /ˈsεtːe/ | 5 | /ˈtʃiŋkwe/ | 14 | 8-2 | /ˈotːo/-/ˈdue/ | 6-1 | /ˈsεi/-/ˈuːno/ |

| 15 | 8 | /ˈotːo/ | 10 | /ˈdiεtʃi/ | 15 | 10-4 | /ˈdiεtʃi/-/ˈkwatːro/ | 2-5 | /ˈdue/-/ˈtʃiŋkwe/ |

| 16 | 6 | /ˈsεi/ | 2 | /ˈdue/ | 16 | 9-5 | /ˈnɔve/-/ˈtʃiŋkwe/ | 4-3 | /ˈkwatːro/-/ˈsεtːe/ |

| 17 | 9 | /ˈnɔve/ | 4 | /ˈkwatːro/ | 17 | 4-9 | /ˈkwatːro/-/ˈnɔve/ | 10-5 | /ˈdiεtʃi/-/ˈtʃiŋkwe/ |

| 18 | 1 | /ˈuːno/ | 9 | /ˈnɔve/ | 18 | 6-4 | /ˈsεi/-/ˈkwatːro/ | 1-9 | /ˈuːno/-/ˈnɔve/ |

| 19 | 2 | /ˈdue/ | 8 | /ˈotːo/ | 19 | 1-10 | /ˈuːno/-/ˈdiεtʃi/ | 5-8 | /ˈtʃiŋkwe/-/ˈotːo/ |

| 20 | 10 | /ˈdiεtʃi/ | 3 | /ˈsεtːe/ | 20 | 4-6 | /ˈkwatːro/-/ˈsεi/ | 9-2 | /ˈnɔve/-/ˈdue/ |

| Single | Channel 1 | Channel 2 | Double | Channel 1 | Channel 2 | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| DDT | LEFT | RIGHT | DDT | LEFT | RIGHT | ||||

| TRIAL # | Stim. | Resp. | Stim. | Resp. | TRIAL # | Stim. | Resp. | Stim. | Resp. |

| 1 | 1 | 7 | 1 | 6-1 | 8-2 | ||||

| 2 | 8 | 4 | 2 | 2-5 | 10-4 | ||||

| 3 | 2 | 6 | 3 | 4-7 | 9-5 | ||||

| 4 | 7 | 4 | 4 | 8-6 | 7-1 | ||||

| 5 | 1 | 9 | 5 | 9-2 | 4-6 | ||||

| 6 | 7 | 5 | 6 | 7-10 | 2-4 | ||||

| 7 | 5 | 8 | 7 | 5-8 | 1-10 | ||||

| 8 | 1 | 2 | 8 | 2-9 | 5-7 | ||||

| 9 | 7 | 10 | 9 | 10-5 | 4-9 | ||||

| 10 | 6 | 2 | 10 | 1-9 | 6-4 | ||||

| 11 | 10 | 7 | 11 | 7-1 | 8-6 | ||||

| 12 | 4 | 9 | 12 | 5-7 | 2-9 | ||||

| 13 | 8 | 1 | 13 | 2-4 | 7-10 | ||||

| 14 | 7 | 5 | 14 | 8-2 | 6-1 | ||||

| 15 | 8 | 10 | 15 | 10-4 | 2-5 | ||||

| 16 | 6 | 2 | 16 | 9-5 | 4-7 | ||||

| 17 | 9 | 4 | 17 | 4-9 | 10-5 | ||||

| 18 | 1 | 9 | 18 | 6-4 | 1-9 | ||||

| 19 | 2 | 8 | 19 | 1-10 | 5-8 | ||||

| 20 | 10 | 7 | 20 | 4-6 | 9-2 | ||||

| # CORRECT | ____ x 2.5 = % | ____x 2.5 = % | # CORRECT | ____ x 2.5 = % | ____x 2.5 = % | ||||

| Single DDT | Single DDT | Double DDT | Double DDT | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Right ear | Left ear | Right ear | Left ear | |

| English DDT | 100 ± 0 | 100 ± 0 | 90.1 ± 7.5 | 84.4 ± 9.7 |

| (100-100) | (100-100) | (78-100) | (62-98) | |

| Italian DDT “ translated ” | 99.8 ± 0.6 | 100 ± 0 | 96 ± 5.3 | 97 ± 4.5 |

| (98-100) | (100-100) | (85-100) | (88-100) | |

| Final adapted Italian DDT “Italian DDT” | 99.8 ± 0.4 | 99.7 ± 0.6 | 96 ± 5.3 | 95.8 ± 5.3 |

| (98-100) | (98-100) | (85-100) | (82-100) |

| Single DDT Right ear (%) | Single DDT | Double DDT | Double DDT | Reference values Double DDT right | Reference values Double DDT leff | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Left ear (%) | Right ear (%) | Left ear (%) | ear 6 | ear 6 | ||

| Age 6(n = 3) | 93.3 ± 11.5 | 83.3 ± 10.4 | 83.3 ± 7.6 | 55.8 ± 32.2 | - | - |

| (80-100) | (75-95) | (75-90) | (20-82) | |||

| Age 7(n = 9) | 99.4 ± 1.7 | 82.8 ± 21.2 | 76.4 ± 19.5 | 53.9 ± 14.7 | 70% | 55% |

| (95-100) | (30-100) | (32.5-92.5) | (25-72.5) | |||

| Age 8(n = 102) | 95.1 ± 10.7 | 90.9 ± 12.7 | 77.4 ± 17.6 | 70.9 ± 16.3 | 75% | 65% |

| (25-100) | (35-100) | (0.9-100) | (25-97.5) | |||

| Age 9(n = 18) | 95.0 ± 5.8 | 95.7 ± 6.1 | 80.7 ± 19.2 | 78.2 ± 21.7 | 80% | 75% |

| (85.-100) | (85-100) | (42.5-100) | (40-100) | |||

| Age 10(n = 4) | 100.0 ± 0.0 | 92.5 ± 3.5 | 96.5 ± 1.8 | 85.0 ± 7.1 | 85% | 78% |

| (100-100) | (90-95) | (95-97.5) | (80-90) |

References

- Martini A, Morra B, Cornacchia L. Influence of pre-voicing duration on dichotic performance. Audiology. 1983;22:162-166. doi:https://doi.org/10.3109/00206098309072778

- Lotfi Y, Moossavi A, Javanbakht M. Auditory efferent system; a review on anatomical structure and functional bases. Glob J Oto. 2019;21. doi:https://doi.org/10.19080/GJO.2019.21.556051

- Sardari S, Pourrahimi A, Talebi H. Symmetrical electrophysiological brain responses to unilateral and bilateral auditory stimuli suggest disrupted spatial processing in schizophrenia. Sci Rep. 2019;9. doi:https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-019-52931-x

- Zhang Q, Hu X, Hong B. A hierarchical sparse coding model predicts acoustic feature encoding in both auditory midbrain and cortex. PLoS Comput Biol. 2019;15. doi:https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pcbi.1006766

- Broadbent D. The role of auditory localization in attention and memory span. J Exp Psychol. 1954;47:191-196. doi:https://doi.org/10.1037/h0054182

- Kimura D. Cerebral dominance and the perception of verbal stimuli. Can J Psychol Rev Can Psychol. 1961;15. doi:https://doi.org/10.1037/h0083219

- Musiek F. Assessment of central auditory dysfunction: the dichotic digit test revisited. Ear Hear. 1983;4:79-80. doi:https://doi.org/10.1097/00003446-198303000-00002

- Kim G, Kim H, Kim H. Central auditory processing disorder in patients with amnestic mild cognitive impairment. Behav Neurol. 2022;2022. doi:https://doi.org/10.1155/2022/9001662

- Wydler A, Perret E. Auditory and visual perception of simultaneous verbal and nonverbal stimuli. Experientia. 1977;33:239-240. doi:https://doi.org/10.1007/BF02124088

- Saadon-Grosman N, Loewenstein Y, Arzy S. The ‘creatures’ of the human cortical somatosensory system. Brain Commun. 2020;2. doi:https://doi.org/10.1093/braincomms/fcaa003

- Gresele A, Garcia M, Torres E. Bilingualism and auditory processing abilities: performance of adults in dichotic listening tests. Codas. 2013;25:506-512. doi:https://doi.org/10.1590/S2317-17822014000100003

- Rezapour M, Abdollahi F, Delphi M. Normalization and reliability evaluation of Persian version of two-pair dichotic digits in 8 to 12-year-old children. Iran Rehabil J. 2016;14:115-120. doi:https://doi.org/10.18869/nrip.irj.14.2.115

- Savino M. Intonational features for identifying regional accents of Italian. Proceedings of the Annual Conference of the International Speech Communication Association, INTERSPEECH.:2423-2426. doi:https://doi.org/10.21437/Interspeech.2009-305

- De Groote E, De Keyser K, Santens P. Future perspectives on the relevance of auditory markers in prodromal Parkinson’s disease. Front Neurol. 2020;11. doi:https://doi.org/10.3389/fneur.2020.00689

- Martini A, Bovo R, Agnoletto M. Dichotic performance in elderly Italians with Italian stop consonant-vowel stimuli. Audiology. 1988;27:1-7. doi:https://doi.org/10.3109/00206098809081568

- Manti F, Giovannone F, Ciancaleoni M. Psychometric properties and validation of the Italian Version of ages & stages questionnaires third edition. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2023;20. doi:https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20065014

- Anderson K. Hearing conservation in the public schools revisited. Semin Hear. 1991;12:340-358. doi:https://doi.org/10.1055/s-0028-1085507

- Mukari S, Keith R, Tharpe A. Development and standardization of single and double dichotic digit tests in the Malay language. Int J Audiol. 2006;45:344-352. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/14992020600582174

- Jutras B, Mayer D, Joannette E. Assessing the development of binaural integration ability with the French dichotic digit test: Ecoute Dichotique de Chiffres. Am J Audiol. 2012;21:51-59. doi:https://doi.org/10.1044/1059-0889(2012/10-0040)

- Serra S, Diaz Nocera A, Brizuela M. Patrón de repuestas y latencias ern test de dígitos dicóticos en normoacústicos con especialización auditiva [Answers and latencies dichotic digit test normoacoustic majoring in hearing]. Rev Fac Cien Med Univ Nac Cordoba. 2017;74:18-25.

- Skarzynski P, Czajka N, Zdanowicz R. Normative values for tests of central auditory processing disorder in children aged from 6 to 12 years old. J Commun Disord. 2024;109. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jcomdis.2024.106426

- Mattsson T, Follestad T, Andersson S. Normative data for diagnosing auditory processing disorder in Norwegian children aged 7-12 years. Int J Audiol. 2018;57:10-20. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/14992027.2017.1366670

- Neijenhuis K, Snik A, Priester G. Age effects and normative data on a Dutch test battery for auditory processing disorders. Int J Audiol. 2002;41:334-346. doi:https://doi.org/10.3109/14992020209090408

- Lee T, Rieke C, Niemczak C. Assessment of central auditory processing in children using a novel tablet-based platform: application for low- and middle-income countries. Otol Neurotol. 2024;45:176-183. doi:https://doi.org/10.1097/MAO.0000000000004085

- de Bode S, Sininger Y, Healy E. Dichotic listening after cerebral hemispherectomy: methodological and theoretical observations. Neuropsychologia. 2007;45:2461-2466. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neuropsychologia.2007.03.026

- Moulden A, Persinger M. Delayed left ear accuracy during childhood and early adolescence as indicated by Roberts’ Dichotic Word Listening Test. Percept Mot Skills. 2000;90:893-898. doi:https://doi.org/10.2466/pms.2000.90.3.893

- Khavarghazalani B, Farahani F, Emadi M. Auditory processing abilities in children with chronic otitis media with effusion. Acta Otolaryngol. 2016;136:456-459. doi:https://doi.org/10.3109/00016489.2015.1129552

- Asbjørnsen A, Holmefjord A, Reisæter S. Lasting auditory attention impairment after persistent middle ear infections: a dichotic listening study. Dev Med Child Neurol. 2000;42:481-486. doi:https://doi.org/10.1017/s001216220000089x

- Bellis T, Anzalone A. Intervention approaches for individuals with (central) auditory processing disorder. Contemp Issues Commun Sci Disord. 2008;35:143-153. doi:https://doi.org/10.1044/cicsd_35_F_143

- Taneja N. Comprehensive CAPD Intervention Approaches. Otolaryngol – Open J. Published online 2019:S24-S28. doi:https://doi.org/10.17140/OTLOJ-SE-1-106

- Floegel M, Fuchs S, Kell C. Differential contributions of the two cerebral hemispheres to temporal and spectral speech feedback control. Nat Commun. 2020;11. doi:https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-020-16743-2

- Stipdonk L, Boon R, Franken M. Language lateralization in very preterm children: associating dichotic listening to interhemispheric connectivity and language performance. Pediatr Res. 2022;91:1841-1848. doi:https://doi.org/10.1038/s41390-021-01671-8

- Tervaniemi M, Hugdahl K. Lateralization of auditory-cortex functions. Brain Res Brain Res Rev. 2003;43:231-246. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.brainresrev.2003.08.004

Downloads

License

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

Copyright

Copyright (c) 2025 Società Italiana di Otorinolaringoiatria e chirurgia cervico facciale

How to Cite

- Abstract viewed - 622 times

- PDF downloaded - 100 times