Audiology

Vol. 45: Issue 5 - October 2025

Parent-child interaction and early pragmatic, auditory and linguistic abilities in deaf children

Abstract

Objectives. To describe the Parent-Child Interaction (PCI) in prelingually deaf children with hearing aids and cochlear implants; to evaluate correlations between PCI, parental stress and family participation in the intervention programme, as well as between PCI and auditory and spoken language abilities.

Methods. 20 children (12 males, 8 females; mean age 21.8 ± 4.2 months) received a test battery including Categories of Auditory Performance (CAP), Social Conversational Skills Rating Scale for Assertiveness (SCS-A) and for Responsiveness (SCS-R), MacArthur-Bates Communicative Development Inventories (M-BCDI). PCI was assessed by video analysis, while parental stress and family participation were assessed with the Parenting Stress Index Short Form questionnaire (PSI) and Familiar Involvement Rate Scale (FIRS), respectively.

Results. PCI style was “tutorial” in 15%, “modulated control” in 40%, “directive” in 20% and “asynchronous” in 25% of cases. A significant correlation was found between PCI and FIRS score, between PCI and CAP score, and between PCI and SCS-A rating scale score.

Conclusions. Assessment of PCI in deaf children is important because it relates to family participation in the intervention programme and affects the development of auditory and pragmatic abilities.

Introduction

It is widely known that deafness interferes with normal language development, because it influences the child’s ability to access spoken language. Ninety-five percent of deaf babies are born in hearing families that use oral language to communicate with their children 1.

For hearing parents of deaf children, parent-child communication takes on a central role. They must actively learn new, different communication strategies, regardless of the mode of communication (oral language, sign language, or a combination of both). This adaptation process can result in disrupted interactions that put a strain on parents and children and, in turn, can negatively affect parenting roles and responsibilities. Hearing mothers of deaf children may use few words, with the result of low-quality language input 2,3. Studies in the literature have shown that hearing parents of deaf children are more likely to be directive, even intrusive, with their child, and that they should be less “attuned” to the child’s need to visually and tactilely explore the environment 4,5. Desjardin and Eisenberg 6 have investigated the employment of facilitative language techniques in implanted children. Their results suggest that the use of higher language techniques such as recast correlates with the development of receptive language abilities, whereas the use of open-ended questions is related to the development of expressive language skills. Hearing parents tend to stimulate their deaf children’s speech through requests rather than conversation, which means children have less experience with two-way interactions and receive less feedback on their communicative attempts 7.

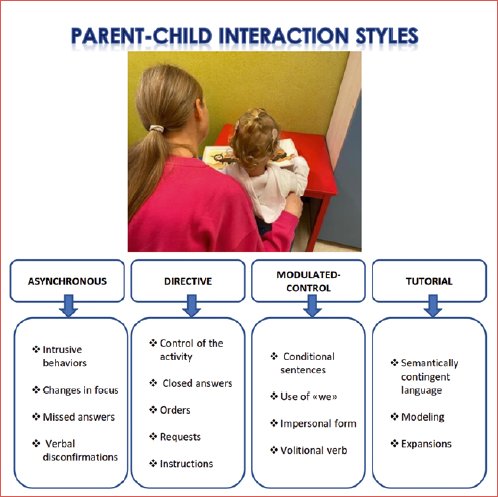

Parent-Child Interaction (PCI) style implies a mutual, face-to-face, dyadic relationship between parents and child. A good interaction is based on maternal sensitivity in providing appropriate and responsive linguistic input, in order to promote positive social-emotional development and improve the child’s communication skills 7,8. According to Bonifacio and Stefani 9, PCI style can be categorised in four types: “tutorial”, “modulated control”, “directive” and “asynchronous”. When a child has a language delay, the tutorial PCI style appears to be the most appropriate, and has been correlated with better outcomes 10. An early identification of PCI style and an adequate intervention aimed at improving the type of interaction can be decisive in stimulating early auditory-perceptual skills and promoting the development of spoken language in deaf children 11. Another important issue that can influence both PCI and outcomes in deaf children is the parenting stress that occurs when hearing parents feel they are unable to care for a deaf child on a daily or long-term basis. Daily concerns include the management of Hearing Aid (HA) and/or Cochlear Implant (CI), the need to attend health appointments, and the language model for the child. Long-term issues include the need to make interventional and educational choices, the financial cost of rehabilitation-related care, the difficulty in providing emotional support to the child and in dealing with their inclusion in a social context 12,13. Parental stress may influence practical and emotional involvement of parents, correlating with poorer social-emotional functioning, cognitive development and language ability of the child more than the degree of hearing impairment 14,15.

Although current guidelines on deafness treatment and rehabilitation 16 recognise the importance of PCI and recommend an active role of parents in the intervention programme, at present it is not clear how therapeutic interventions should be conducted in clinical practice to improve PCI style. For these reasons, PCI may be a topic of great interest for its possible implications in the auditory and linguistic outcome of deaf children. A recent systematic review by Curtin et al. 7 provides some recommendations, such as collecting information from both children and their parents about level of deafness, amplification use and parent-child communication profile, using validated scales.

The primary aim of this observational, cross-sectional study is to describe PCI style in a cohort of prelingually deaf children with HA or CI. The secondary aim is to evaluate the relationship between PCI style and parental stress and the quality of family participation in the intervention programme, as well as between PCI style and the development of auditory and linguistic skills in early childhood.

Materials and methods

Patients

We enrolled 20 deaf patients (12 males, 8 females; mean age 21.8 ± 4.2 months; mean duration of HA or CI use = 14.2 ± 2.2 months; 9 using HA and 11 a simultaneous bilateral CI) from the Phoniatric Unit of the Fondazione Policlinico A. Gemelli IRCCS of Rome.

Inclusion criteria were: chronological age between 12 and 30 months; prelingual bilateral deafness of severe or profound degree diagnosed between 3 and 6 months; use of HA or CI for at least 6 months; device use (HA or CI) for at least 8 hours a day; hearing parents; monolingual Italian-speaking family, absence of attention deficit and neurodevelopmental disorders.

Exclusion criteria were: chronological age < 12 months and > 30 months; mild and moderate hearing loss; postlingual deafness; late diagnosis of deafness; device use less than 8 hours a day; deaf parents; multilingual speaking family, associated attention deficit and neurodevelopmental disorders.

Children of the HA Group (6 males and 3 females; mean chronological age 20.5 ± 5 months; mean duration of device use = 13.3 ± 4.4 months) had moderate-to-severe hearing loss (0.5-4 kHz PTA > 55 -≤ 70 dB HL). All had bilateral digital retroauricolar devices.

Children of the CI Group (6 males and 5 females; mean chronological age 22.9 ± 4.2 months; mean duration of CI use = 13.8 ± 3 months) had a severe or profound hearing loss (0.5-4 kHz PTA > 70 dB). All had normal cochlear anatomy and were implanted with cochlear (Cochlear, Sydney, Aus) devices with full electrode array insertion.

Table I summarises the demographic and clinical data of the sample.

At the moment of the enrollment in the study children in both groups had been attending an oral habilitation programme twice a week for at least six months and were at a prelingual or transitional level of language development as measured through the Language Ability Profile (PALS) by the Nottingham Early Assessment Package (NEAP©) 17.

Moreover, they received a test battery to assess speech perception, as well as communicative and language development. A thorough assessment of PCI style, parental stress and family participation in the intervention programme was carried out.

Speech perception

Categories of auditory performance (CAP) is a scale of auditory perceptive abilities ranging from 0 (‘‘displays no awareness of environmental sounds’’) to 7 (‘‘can use the telephone with a familiar speaker’’), included in the NEAP17 and used to rate everyday auditory performance of paediatric CI users.

In our study, ratings were given by a speech therapist who was not involved in the child intervention programme.

Communication/language abilities

The Italian version of the Social Conversational Skills Rating Scale (SCS) 18,19 is a questionnaire administered to parents, which was developed to evaluate conversational skills in children aged 12 to 36 months and to suggest pragmatic intervention objectives. It consists of 25 items: 15 items assess the children’s assertiveness (SCS-A), and 10 items their responsiveness (SCS-R). Parents are asked to rate each item according to the perceived frequency of occurrence (from 1 = never to 5 = always). The score of assertiveness and responsiveness is expressed as average and total score, so that three levels of socio-conversational skills can be obtained: Level 1 (average score ≤ 2.9, absence or infrequent ability); Level 2 (average score between 3 and 3.9, emergent skill); Level 3 (average score between 4 and 5, developed ability).

The Italian version of the MacArthur–Bates Communicative Development Inventory (M-BCDI) 20 (Primo Vocabolario del Bambino, PVB) 21 is a questionnaire for parents investigating the development of the first language and communication abilities (comprehension of simple sentences in familiar and contextualised situations, production of different types of actions and gestures, vocabulary and emergence of grammar, first gesture/word combinations). It is composed of two questionnaires: “Gestures and Words” for children aged between 8 and 17 months, and the “Words and Sentences” for children aged between 18 and 36 months. The score is calculated differently (percentiles, mean and standard deviation, percentage). For the purposes of this study, we evaluated the number of words understood in relation to hearing age, considering four categories: 4 = 50th-25th percentile; 3 = 25th-10th percentile; 2 = 10th-5th percentile; 1 = < 5th percentile.

Parent-child interaction (PCI)

Video analysis according to Tait, Lutman and Nikolopoulos22 was used to assess PCI style through the frame-by-frame coding analysis. Parents were asked to interact with their children and play with them, in a quiet, bright room, with the camera facing away from the light source and the child sitting at a right angle to the window. The camera recorded the child almost full-face, with a profile view of the adult. The session lasted between 5 and 10 minutes, and a 5-minute section was described. Four areas were measured: turn-taking, autonomy, eye contact and auditory awareness. The score was calculated as percentage of the total number of behaviors observed in the four areas according to Tait, Lutman and Nikolopoulos 22. Depending on the distribution of the percentage in descending order, the PCI was divided in four categories according to Bonifacio and Hvastja Stefani 9: tutorial (category 3), modulated control (category 2), directive (category 1) and asynchronous (category 0). A speech-language pathologist blind to the study objectives and not involved in the child intervention programme analysed the video sessions.

Parental stress and family participation assessment

Parenting Stress Index (PSI) Short Form 23 is a standardised survey comprising 36 items with 5 possible answers for each item. A score from 1 to 5 is assigned to each answer (1 = strongly disagree and 5 = strongly agree). The survey assesses three domains: Parent Distress (PD), Parent-Child Dysfunctional Interaction (P-CDI) and Difficult Child (DC). Values < 15th percentile are considered within the upper range of normality, values between the 15th and the 80th percentile as normal, and values equal to or exceeding the 85th percentile as clinically significant. We considered three categories: 3 (< 15th percentile), 2 (15th-80th percentile) and 1 (> 85th percentile).

Family Involvement Rate Scale 24 evaluates the quality of family participation in the intervention programme through a score from 1 to 5 (1 = limited participation; 2 = below average participation; 3 = average participation; 4 = good participation; 5 = ideal participation).

A member of the medical team who interacted with the family but not directly involved in the intervention evaluated the level of parental participation. Before assigning their ratings, the rater is given specific descriptions of characteristics representing each category and is asked to consider issues such as family adjustment, level of session participation, effectiveness of communication with the child, and parental advocacy.

Statistical analysis

For statistical analysis we used the MedCalc package (version 12, Marienkerke, Belgium). The Kolmogorov-Smirnov test was employed to assess the distribution of the continuous variables. Parametric or non-parametric tests were applied depending on data distribution. Significance was considered for p values < 0.05.

Results

The comparison of results in the HA and CI group did not show any significant differences for chronological age, hearing age and gender (p > 0.05). PCI was “tutorial” in 3/20 (15%) cases, “modulated control” in 8/20 (40%), “directive” in 4/20 (20%) and “asynchronous” in 5/20 (25%). In the HA Group, PCI was “tutorial” in 2/9 (22%) cases, “modulated control” in 5/9 (56%), “directive” in 1/9 (11%), “asynchronous” in 1/9 (11%), while in the CI Group, PCI was “tutorial” in 1/11 (9%) cases, “modulated control” in 3/11 (27%), “directive” in 3/11 (27%) and “asynchronous” in 4/11 (37%) (Tab. II). The PCI style was not influenced by gender (p = 0.93, χ = 0.008), with tutorial and asynchronous styles being almost equally distributed between males and females.

Results of the Family Involvement Rate Scale (FIRS), Parenting Stress Index (PSI), Social Conversational Skills Rating Scale for child’s assertiveness (SCS-A) and for responsiveness (SCS-R), MacArthur-Bates Communicative Development Inventory (M-BCDI) and Categories of Auditory Performance (CAP) are reported in Table II for both groups.

The Kolmogorov-Smirnov test showed a non-parametric distribution of PCI, CAP, SCS, M-BCDI and PSI.

Spearman’s rank analysis demonstrated a significant correlation between PCI and FIRS (r = 0.8; p < 0.001) (Fig. 1), CAP (r = 0.45; p = 0.04) (Fig. 2) and SCS-A (r = 0.48; p = 0.03) (Fig. 3). No significant correlation was found between PCI and SCS-R, although the correlation approached significance (p = 0.1).

Statistical analysis also showed a significant correlation between CAP and M-BCDI (r = 0.66; p = 0.001), SCS-A (r = 0.75; p < 0.001), and SCS-R (r = 0.86; p < 0.001). It is worth mentioning that M-BCDI bears a very high correlation to both SCS-A (r = 0.85, p < 0.001) and SCS-R (r = 0.68, p < 0.001). However, no significant correlation was found between type of PCI and PSI or M-BCDI.

Discussion

The results of our cross-sectional study showed that only a minority (15%) of parents use a tutorial style in communication. On the one hand, this probably reflects an ineffective parent-child interaction, while on the other it denotes a lack of guidance for parents in the early stages of rehabilitation. In this respect, the poor availability of evaluation tools testing PCI is a critical problem.

A recent review 7 on 61 articles reported that assessment of parent-child interaction is not standardised. This aspect can be understandable, considering the complexity of the variables involved, such as joint attention/engagement, linguistic and visual strategies, eye contact, parental sensitivity, type and use of gesture and contingent responses. Parents who are sensitive or receptive to their children’s needs will provide timely and contingent responses to their communicative behaviour. Responses may include language (words, signs, repetitions, questions, and sentence patterns), as well as additional communication behaviours (facial expressions, gestures, touch, and tone). For this reason, the main evaluation tool in all the studies cited in the review remains videoanalysis. Recently, Rebesco et al. 25 presented a new frame-by-frame video analysis which takes up and extends Tait’s video analysis, including linguistic, paralinguistic and metalinguistic parameters. Linguistic parameters comprised communicative mode and vocalisation type, while paralinguistic parameters are classified in three sub-areas: turn-taking, auditory awareness and eye contact. Metalinguistic parameters included a description of joint attention and the parental communication style.

Among the variables included in the assessment of PCI style, a recent meta-analysis by Lammertink et al. 26 focused on the importance of joint attention, intended as the complex of social cognitive behaviours (including gaze, pointing, and visual attention) in which the parent and child synchronously focus on the same object, action, event, or person. Hearing parents of deaf children may achieve fewer moments of joint attention. This is possibly due to the different hearing status, making it difficult to apply strategies of interaction that enhance the synchronous presentation of auditory and visual information, as happens when parents name or share objects. Moreover, feelings of low self-efficacy may discourage parents from using facilitative language techniques, as demonstrated by Desjardin, Doll and Stika 2, showing that the language skills of young CI users are conditioned by their mothers’ perception of involvement and self-efficacy. The review by Curtin et al. 7 shows that parental behaviours are associated with child language scores. Specifically, joint engagement is correlated with the development of the receptive and expressive language skills, while parental sensitivity is correlated with expressive language and predicts language growth over time.

Parents with a good level of sensitivity and responsiveness to their child may also have a good compliance or a better adherence to therapy, in contrast to what happens with parents using an asynchronous style, meaning that the former may have a higher level of therapeutic compliance. Therefore, it is not surprising that PCI correlates with the degree of family participation. Parents with a high degree of family participation are more involved in audiologic, speech and language programmes, so they can be able to support the cognitive and linguistic development of their children.

Another interesting correlation was found between PCI and speech perception. The correlation between PCI and CAP has not been described in the literature to date. It could be hypothesised that as parents see an improved responsiveness by the child, they increase their level of interaction. Parents using a tutorial PCI style are more likely to give value to the auditory experience, stimulating the incidental learning and reinforcing the auditory-verbal skills. In particular, with tutorial PCI style children may receive a better integration of the cognitive aspects of language and enjoy a higher quality of verbal perception. On the contrary, parents with asynchronous or directive PCI styles will be more focused on their child’s performance, rather than on auditory experiences.

The correlation between PCI and communication and linguistic skills in our study showed significance only with SCS-A. The lack of correlation between PCI and vocabulary skills may be explained by the low mean age in our sample, making it difficult to assess a direct effect of PCI on vocabulary. Despite this, a tutorial PCI style is related to the improvement of pragmatic skills, as far as assertiveness is concerned. Social-conversational skills have been demonstrated to be the precursors of vocabulary development, as demonstrated in children with CI by Guerzoni et al. 27 and confirmed by our data.

In the light of these considerations, parent-child support is necessary in the rehabilitation programme for deafness. A pilot RCT by Roberts 28 has developed the Parent-Implemented Communication Treatment. In this training, parents in the experimental group were taught to encourage and reinforce the communication attempts of their children using four different strategies: visual (e.g., sitting face to face with the child, moving the object to the child’s attentional focus or waiting until the child looks before starting an interaction), interactive (e.g., following the child’s lead or choosing interesting toys), responsive (e.g., responding to all communicative attempts of the child or balancing turn taking) and linguistically stimulating (e.g., adding spoken words to the interaction or expanding child productions). They received weekly, hour-long sessions for 6 months and reported better results in terms of turn-taking, using gestures, imitating/mirroring the child’s action, and sitting face to face, which are all considered as prelingual speech skills. A systematic review by Giallini et al. 11 evaluated the effectiveness of parent-training programmes in terms of benefits in enhancing parental sensitivity, responsiveness and promoting language development in deaf children. The results appear promising, but other studies are needed to understand the reference models and the modality of performing the training (individual, group or mixed sessions), as well as the intensity and the duration of the programme. Other recent works suggest the need for behavioural parent-training programmes 14, and propose a Parent-Child Interaction Therapy where children work directly with their caretaker and a therapist, and everyone involved develops new skills 29.

The limits of the present study are the small sample size and lack of longitudinal data which did not allow us to see how the parent-child interaction changes over time. Furthermore, there is no comparison with a control group including deaf children of deaf parents.

Conclusions

The present cross-sectional study uses a PCI ranking from “tutorial” to “asynchronous”, to correlate PCI style with multiple variables, such as family participation, auditory-perceptual abilities, and pragmatic skills. Our results confirm that parent-child interaction must be considered as an important part of the assessment and intervention in childhood deafness because it is related to therapeutic compliance and development of pragmatic and auditory abilities. For this reason, standardised assessment tools are desirable, as well as shared clinical practice guidelines. Moreover, it is necessary to improve parental counselling programmes, in order to help parents understand and apply tutorial strategies that guarantee better language learning opportunities for their deaf children.

Conflict of interest statement

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Funding

This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Author contributions

FZ: design of the study, interpretation of data and manuscript writing, revision and final approval; GM: design of the study, statistical analysis, writing, revision and final approval of manuscript; TDC: acquisition, analysis and interpretation of data and manuscript revision; PMP: analysis and interpretation of data, manuscript writing, revision and final approval; YL: acquisition, analysis and interpretation of data, revision and final approval of manuscript; DR: interpretation of data, revision and final approval of manuscript; LDA: design of the study, interpretation of data, revision and final approval of the manuscript.

Ethical consideration

This study was approved by the Institutional Ethics Committee by the institutional review board (Fondazione Policlinico Universitario A. Gemelli, ID 5685 Prot. N 0014249/23).

The research was conducted ethically, with all study procedures being performed in accordance with the requirements of the World Medical Association’s Declaration of Helsinki.

Written informed consent was obtained from each participant/patient for study participation and data publication.

History

Received: May 15, 2024

Accepted: November 2, 2024

Figures and tables

Figure 1. Spearman’s rank correlation between parent-child interaction (PCI - y axis) and Familiar Involvement Rate Scale (FIRS - x axis).

Figure 2. Spearman’s rank correlation between parent-child interaction (PCI - y axis) and Categories of Auditory Performance (CAP - x axis).

Figure 3. Spearman’s rank correlation between parent-child interaction (PCI - y axis) and Social Conversational Skills rating scale - Assertiveness scale (SCS_A - x axis).

| Patient | Gender | HA/CI | Age (months) | Aetiology of deafness |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | M | CI | 22 | Prematurity |

| 2 | M | CI | 26 | Prematurity |

| 3 | F | CI | 19 | Genetic, non-syndromic |

| 4 | F | CI | 18 | Genetic, non-syndromic |

| 5 | F | CI | 25 | Unknown |

| 6 | F | CI | 22 | Genetic, non-syndromic |

| 7 | M | HA | 17 | Genetic, non-syndromic |

| 8 | F | CI | 20 | Genetic, non-syndromic |

| 9 | M | HA | 21 | Genetic, non-syndromic |

| 10 | F | HA | 16 | Prematurity |

| 11 | M | HA | 25 | Pendred syndrome |

| 12 | M | HA | 14 | Pendred syndrome |

| 13 | M | HA | 25 | Genetic (X-linked) |

| 14 | M | HA | 23 | Genetic, non-syndromic |

| 15 | M | CI | 28 | Genetic, non-syndromic |

| 16 | F | HA | 18 | Genetic, non-syndromic |

| 17 | M | CI | 30 | Unknown |

| 18 | F | HA | 26 | Pendred syndrome |

| 19 | M | CI | 24 | Genetic, non-syndromic |

| 20 | M | CI | 18 | Genetic, non-syndromic |

| HA: hearing aids; CI: cochlear implant. | ||||

| Patient | Gender | HA/CI | Age | PCI | FIRS | PSI | SCS-A | SCS-R | M-BCDI | CAP |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | M | CI | 22 | Tutorial | 5 | 3 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 2 |

| 2 | M | CI | 26 | Asynchronous | 1 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| 3 | F | CI | 19 | Directive | 3 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 3 | 3 |

| 4 | F | CI | 18 | Directive | 2 | 3 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 4 |

| 5 | F | CI | 25 | Modulated control | 4 | 3 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 2 |

| 6 | F | CI | 22 | Modulated control | 2 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| 7 | M | HA | 17 | Modulated control | 4 | 2 | 3 | 1 | 3 | 3 |

| 8 | F | CI | 20 | Modulated control | 3 | 2 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 5 |

| 9 | M | HA | 21 | Modulated control | 4 | 3 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 4 |

| 10 | F | HA | 16 | Asynchronous | 2 | 3 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 2 |

| 11 | M | HA | 25 | Modulated control | 3 | 2 | 3 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| 12 | M | HA | 14 | Modulated control | 5 | 3 | 3 | 2 | 4 | 4 |

| 13 | M | HA | 25 | Modulated control | 4 | 3 | 3 | 2 | 4 | 5 |

| 14 | M | HA | 23 | Directive | 3 | 3 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 4 |

| 15 | M | CI | 28 | Asynchronous | 2 | 3 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 3 |

| 16 | F | HA | 18 | Tutorial | 5 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 6 |

| 17 | M | CI | 30 | Asynchronous | 2 | 3 | 3 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

| 18 | F | HA | 26 | Tutorial | 3 | 3 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 4 |

| 19 | M | CI | 24 | Asynchronous | 1 | 3 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 3 |

| 20 | M | CI | 18 | Directive | 2 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 2 |

| HA: hearing aids; CI: cochlear implant; PCI: parent-child interaction; FIRS: Family Involvement Rate Scale; SCS-A: Social-Conversational Skills Rating Scale-Assertiveness; SCS-R: Social-Conversational Skills Rating Scale-Responsiveness; M-BCDI: MacArthur-Bates Communicative Development Inventories; PSI: Parenting Stress Index; CAP: categories of auditory performance. | ||||||||||

References

- Yu C, Stanzione C, Wellman H. Theory-of-mind development in young deaf children with early hearing provisions. Psychol Sci. 2021;32:109-119. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/0956797620960389

- DesJardin J, Doll E, Stika C. Parental support for language development during joint book reading for young children with hearing loss. Commun Disord Q. 2014;35:167-181. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/1525740113518062

- Dirks E, Stevens A, Kok S. Talk with me! Parental linguistic input to toddlers with moderate hearing loss. J Child Lang. 2020;47:186-204. doi:https://doi.org/10.1017/S0305000919000667

- Spencer P, Bodner-Johnson B, Gutfreund M. Interacting with infants with a hearing loss: what can we learn from mothers who are deaf?. J Early Interv. 1992;16:64-78.

- Barker D, Quittner A, Fink N. Predicting behavior problems in deaf and hearing children: the influences of language, attention, and parent-child communication. Dev Psychopathol. 2009;21:373-392. doi:https://doi.org/10.1017/S0954579409000212

- DesJardin J, Eisenberg L. Maternal contributions: supporting language development in young children with cochlear implants. Ear Hear. 2007;28:456-469. doi:https://doi.org/10.1097/AUD.0b013e31806dc1ab

- Curtin M, Dirks E, Cruice M. Assessing parent behaviours in parent-child interactions with deaf and hard of hearing infants aged 0-3 years: a systematic review. J Clin Med. 2021;10. doi:https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm10153345

- Quittner A, Cruz I, Barker D. Effects of maternal sensitivity and cognitive and linguistic stimulation on cochlear implant users’ language development over four years. J Pediatr. 2013;162:343-348. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpeds.2012.08.003

- Bonifacio S, Hvastja Stefani L. Le strategie comunicative come modalità di intervento nel bambino parlatore tardivo: analisi di due casi clinici. Psicologia Clinica dello Sviluppo. 2007;11:457-476.

- Longobardi E, Rienzi S, Spataro P. Communicative functions and mind-mindedness in mother-child interactions at 16 months of age. Psicologia Clinica dello Sviluppo. 2015;19:345-355.

- Giallini I, Nicastri M, Mariani L. Benefits of parent training in the rehabilitation of deaf or hard of hearing children of hearing parents: a systematic review. Audiol Res. 2021;11:653-672. doi:https://doi.org/10.3390/audiolres11040060

- Sarant J, Garrard P. Parenting stress in parents of children with cochlear implants: relationships among parent stress, child language, and unilateral versus bilateral implants. J Deaf Stud Deaf Educ. 2014;19:85-106. doi:https://doi.org/10.1093/deafed/ent032

- Jean Y, Mazlan R, Ahmad M. Parenting stress and maternal coherence: mothers with deaf or hard-of-hearing children. Am J Audiol. 2018;27:260-271. doi:https://doi.org/10.1044/2018_AJA-17-0093

- Studts C, Jacobs J, Bush M. Behavioral parent training for families with young deaf or hard of hearing children followed in hearing health care. J Speech Lang Hear Res. 2022;65:3646-3660. doi:https://doi.org/10.1044/2022_JSLHR-22-00055

- Continisio G, D’Errico D, Toscano S. Parenting stress in mothers of children with permanent hearing impairment. Children (Basel). 2023;10. doi:https://doi.org/10.3390/children10030517

- Year 2019 Position Statement: principles and guidelines for early hearing detection and intervention programs. J Early Hear Detect Interv. 2019;4:1-44. doi:https://doi.org/10.15142/fptk-b748

- Nikolopoulos T, Archbold S, Gregory S. Young deaf children with hearing aids or cochlear implants: early assessment package for monitoring progress. Int J Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol. 2005;69:175-186. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijporl.2004.08.016

- Girolametto L. Development of a parent report measure for profiling the conversational skills of preschool children. Am J Speech-Lang Pathol. 1997;6:25-33.

- Bonifacio S, Girolametto L, Bulligan M. Assertive and responsive conversational skills of Italian-speaking late talkers. Int J Lang Commun Disord. 2007;42:607-623. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/13682820601084386

- Fenson L. MacArthur Communicative Development Inventories: User’s Guide and Technical Manual. Paul H. Brookes; 2002.

- Caselli M, Pasqualetti P, Stefanini S. Parole E Frasi Nel «Primo Vocabolario Del bambino». Nuovi Dati Normativi Fra I 18 E 36 Mesi E Forma Breve Del Questionario. Franco Angeli; 2007.

- Tait M, Lutman M, Nikolopoulos T. Communication development in young deaf children: review of the video analysis method. Int J Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol. 2001;61:105-112. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/s0165-5876(01)00494-3

- Guarino A, Laghi F, Serantoni G. Parenting Stress Index. Giunti O.S.; 2016.

- Moeller M. Early intervention and language development in children who are deaf and hard of hearing. Pediatrics. 2000;106. doi:https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.106.3.e43

- Rebesco R, Colombani A, Handjaras G. Early assessment of communicative competence in children with hearing loss using the Child-Caregiver Communication Assessment through Rebesco’s Evaluation (CC-CARE) method. Int J Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol. 2024;181. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijporl.2024.111927

- Lammertink I, Hermans D, Stevens A. Joint attention in the context of hearing loss: a meta-analysis and narrative synthesis. J Deaf Stud Deaf Educ. 2021;27:1-15. doi:https://doi.org/10.1093/deafed/enab029

- Guerzoni L, Murri A, Fabrizi E. Social conversational skills development in early implanted children. Laryngoscope. 2016;126(9):2098-2105. doi:https://doi.org/10.1002/lary.25809

- Roberts M. Parent-implemented communication treatment for infants and toddlers with hearing loss: a randomized pilot trial. J Speech Lang Hear Res. 2019;62:143-152. doi:https://doi.org/10.1044/2018_JSLHR-L-18-0079

- Curtin M, Thompson L. What is parent-child interaction therapy?. JAMA Pediatr. 2023;177. doi:https://doi.org/10.1001/jamapediatrics.2022.5930

Downloads

License

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

Copyright

Copyright (c) 2025 Società Italiana di Otorinolaringoiatria e chirurgia cervico facciale

How to Cite

- Abstract viewed - 603 times

- PDF downloaded - 173 times