Rhinology

Vol. 45: Issue 6 - December 2025

Novel approach for assessing nasal valve obstruction: a study of nasal valve patency using peak nasal inspiratory flow and flowmetry

Abstract

Objective. The aim of this paper is to compare the results of uing two methods designed to objectify nasal patency in patients with external and internal nasal valve obstruction.

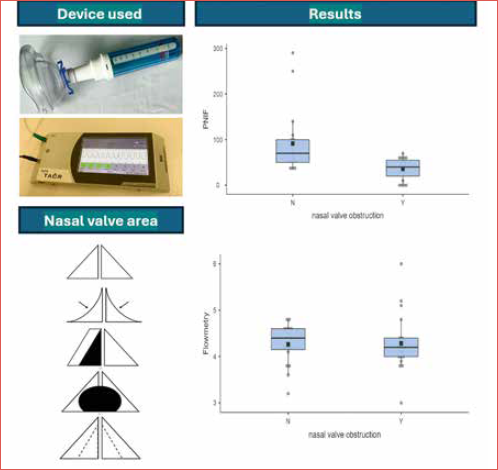

Methods. Nasal flow was measured by a flowmeter (behind the nasal valve area) and peak nasal inspiratory flow (PNIF; in front of the nasal valve area) separately for each side of the nasal cavity.

Results. Data included information from a total of 38 sides of the nasal cavity – 19 sides of the nasal cavity with an obstruction in the area of the nasal valve and 19 sides of the nasal cavity without an obstruction. There were no statistically significant differences in terms of age (p = 0.299), gender (p = 1.000) and flowmetry values (4.28 vs 4.26; p = 0.462) between the two groups. Statistically significant differences between groups were found for visual analogue scale (VAS) of nasal patency (4.99 vs 8.64; p < 0.001) and PNIF scores (36.1 vs 91.6; p = 0.002).

Conclusions. To determine the contribution of obstruction to the clinical condition in the nasal valve area, it is appropriate to use a combination of methods measuring in the area in front of and behind the nasal valve. According to our observations, the combination of PNIF and flowmetry may be advantageous in the evaluation of these patients.

Introduction

Nasal obstruction is a bothersome symptom that has a notable impact on quality of life, emotional function, productivity and the ability to sleep and perform daily activities 1,2. The most common cause of nasal congestion in adults is rhinitis and rhinosinusitis 3, while obstruction in the nasal valve area is one of the less frequent causes 4,5. The nasal valve, and its external and internal components, has been described anatomically as the cross-sectional area of the nasal cavity with the greatest overall resistance to airflow, thus acting as the dominant determinant for nasal inspiration 6.

Aetiologies of external and internal nasal valve dysfunction can be broken down into static and dynamic causes. Static nasal valve dysfunction is seen at rest, due to anatomic narrowness or obstruction; dynamic nasal valve dysfunction occurs when the patient inspires 7. Ideal management of patients with nasal valve obstruction and any other concurrent cause of nasal obstruction can be challenging even for experienced rhinologists 5,8. It is therefore advisable to use a combination of visualisation of external structures of the nose, nasal endoscopy and methods designed to objectify the degree of nasal patency to determine the location of obstruction. There are several methods to objectify nasal obstruction, with rhinomanometry, acoustic rhinometry, and peak nasal inspiratory flow (PNIF) being the most frequently used 9-11. Objectifying nasal obstruction in patients with a nasal valve pathology can be complicated and the results can be biased 12. The aforementioned methods always require good patient cooperation, as the patient must follow the examiner’s instructions and breathe accordingly. Moreover, to achieve consistent results it is important to ensure a proper seal of the facial mask, occlude the contralateral nostril, and prevent oral breathing. Patient reports of nasal obstruction do not always correlate with objective assessments. Rhinomanometry and PNIF measurements using a facial mask can be influenced by mask fit, particularly in men with facial hair.

The biggest disadvantage of rhinomanometry and PNIF is that nasal valve function is not independently assessed, which can affect the results in patients with irregular or narrow nostrils. This can impact clinical decision making about further clinical management.

A new measurement method for objectifying nasal obstruction has been developed, nasal flowmetry, which is designed to objectify nasal patency behind the nasal valve area 13. The nasal flowmeter is a 320x130x32 mm device that is freely portable. Modified nasal cannula is used to test nasal patency – one free end for insertion into the nostril is cut off and blinded with tape. The cannula is then connected to the device and the other free end of the cannula is inserted into one of the patient’s nostrils (Fig. 1). The flow through the cannula from the nasal cavity is then captured by the device for 40 seconds and converted from cubic centimetres to an output voltage, which is graphically expressed on the device screen. Voltage of 3.0 V corresponds to 0 cm of nasal flow, with inspiration and expiration then biasing away from 3.0 V. Measurement with this method requires only minimal patient cooperation. However, flowmetry has not been compared with other methods, except endoscopic examination and subjective patient assessment. Flowmetry was used to assess the relationship between nasal endoscopy findings and continuous positive airway pressure adherence 14.

The aim of this paper is to compare results of two methods designed to objectify nasal patency, one in front of the nasal valve area and the other behind it (Cover figure).

Materials and methods

A total of 26 patients were enrolled in this prospective, monocentric, analytical study, which was conducted in a regional hospital from September 2021 to November 2023.

We included patients with nasal obstruction due to pathology in the area of the nasal valve. To detect this pathology, the external structures of the nose were visualised at steady state and during maximal inspiration (Fig. 2). Next, nasal endoscopy was performed to detect nasal septum deformity or any other anatomical abnormality that could lead to nasal obstruction. The results were divided in 2 groups, the first with nasal valve obstruction and the second without. Mladina classification was used to score nasal septal deformity 15,16. Patients with other conditions that could potentially cause nasal obstruction (e.g. rhinitis, rhinosinusitis, septal perforation, tumours) were excluded.

The subjective assessment of nasal patency was measured using a 10-point visual analogue scale (VAS) for each side of the nasal cavity, when 0 points were total obstruction and 10 points no obstruction.

Nasal flow of each side of the nasal cavity was measured with a flowmeter (Elmet s.r.o., Přelouč, Czech Republic) – nasal flow was measured using a nasal cannula into which the patient breathes quietly for 40 seconds. The result was the average of the measured inspiratory peaks, which considers values between 3.0 V and 6.0 V 13. PNIF was used to measure nasal flow in the area in front of the nasal valve. In-check portable nasal inspiratory flowmeter (Clement Clarke International Ltd, Mountain Ash, United Kingdom) was used. The patient took 3 breaths, and the highest value measured in litres per minute was used as the final result. To measure nasal flow separately on each side, the other side of the nasal cavity was closed with surgical tape.

Jamovi 2.3.26 software (www.jamovi.org) was used for statistical analysis. The characteristics of the groups were described, and the Shapiro-Wilk test was used for the normality test. Two-sample t-test or non-parametric Mann-Whitney test was used to compare groups. P values < 0.05 were considered statistically significant.

Results

From September 2021 to November 2023, a total of 26 patients were enrolled in the study. During our visual observation examination, we found nasal valve obstruction in 13 patients – external nasal valve collapse in 4 patients (2 bilateral and 2 unilateral), narrowing of the internal nasal valve in 3 patients (2 bilateral and 1 unilateral), severe unilateral subluxation of the nasal septum in 4 patients, and substantially wide columella in 2 patients (both bilateral). The data included information from 19 sides of the nasal cavity (Tab. I). We observed a concomitant septal deformity in 8 cases [type 1 (n = 3), type 3 (n = 3) and type 5 (n = 2) according to Mladina classification; Table II]. We were able to obtain data from 19 sides of the nasal cavity in 13 patients with the same nasal septum shape but without obstruction in the nasal valve area, corresponding to the group of patients with nasal valve obstruction (Tab. II). Data from a total of 38 sides of the nasal cavity were statistically analysed. No complications were observed during the examination process.

There were no statistically significant differences in terms of age (p = 0.299), gender (p = 1.000) and flowmetry values (4.28 vs 4.26; p = 0.462) between the 2 groups. Statistically significant differences between groups were found for VAS of nasal patency (4.99 vs 8.64; p < 0.001) and PNIF scores (36.1 vs. 91.6; p = 0.002). Detailed results are shown in Table III.

Discussion

Nasal congestion can have a significant impact on an individual’s quality of life and overall well-being. It can affect emotional function, productivity, and the ability to perform daily activities 1,2. Common causes of nasal congestion in adults include chronic rhinosinusitis and allergic rhinitis 17.

When evaluating a patient with nasal obstruction, it is important to take a thorough history and perform a detailed physical examination. This examination should include an evaluation of both internal and external structures of the nose, as both can contribute to nasal airflow obstruction. Nasal endoscopy may reveal the cause of nasal obstruction due to internal sources such as septal deviation or turbinate hypertrophy. This approach allows the surgeon to formulate an appropriate treatment plan 5.

Nasal valve obstruction is one of the less common causes of nasal congestion and its optimal treatment plan may require rhinoplasty 4,5. Many physicians often perform a septoplasty or rhinoseptoplasty without objectifying the nasal patency prior to surgery. The results of these procedures can sometimes be unsatisfactory 18. Therefore, it is recommended to use a combination of diagnostic methods with highest possible clinical benefit to measure nasal patency in order to optimally determine the treatment plan, since this will lead to improved surgical outcomes and a better quality of life for patients 19.

Many devices have been described to measure nasal patency, some of which are validated and standardised (e.g. rhinomanometry, acoustic rhinometry), and some of which are validated but not yet standardised (e.g. PNIF, flowmetry) 9-11,13. Devices to measure nasal patency are not used frequently in daily practice, with one of the main reasons being non-correlation between subjective assessment and objective measurement 20. The reason for this non-correlation is still debated, with some authors suggesting that nasal valve obstruction or low trigeminal sensitivity are among the many reasons 12,21.

Therefore, it is clear that the nasal valve region plays a key role in nasal breathing. A variety of techniques have been described in the literature to correct nasal valve compromise, but based on current evidence it is impossible to advise a patient on which technique is the most effective 22.

Barnes et al. have pointed out the complexity of objectifying nasal patency in patients with nasal valve pathology due to the frequent presence of associated pathologies causing nasal obstruction (e.g. nasal septal deformity, inferior turbinate hypertrophy) 12.

The Cottle manoeuvre seems to be the most widely used method to detect nasal valve pathology, but one must bear in mind that the result provided by the manoeuvre is non-specific and its interpretation is questionable. In the observation of Das and Spiegel, 97% of the healthy volunteers recruited experienced a significant improvement in nasal patency after the Cottle manoeuvre, although none of the participants required surgery in the nasal valve area 23.

According to observation of Tasca et al., rhinomanometry, performed in a decongested state and after dilation test, was a useful diagnostic tool for preoperative diagnosis of nasal valve obstruction and allowed quantitative evaluation of the beneficial effect of surgical procedures 22. Gagineur et al. concluded that four-phase rhinomanometry is able to reproduce internal valve collapse with high specificity (89.9%) and sensitivity (88.3%) 24. In our observation, we focused not only on measuring nasal airflow in patients with internal valve pathology, but also in patients with external nasal valve pathology by using two devices to objectify nasal patency.

Tikanto et al. combined the Cottle manoeuvre and mucosal decongestion while using acoustic rhinometry to localise possible valve pathology 25. According to their results, the Cottle manoeuvre significantly increased the first minimum cross-sectional area, and the increase was more evident after decongestion of the nasal mucosa. The changes in the second minimum cross-sectional area were not significant, and they concluded that the value of the Cottle manoeuvre in investigating a possible valve insufficiency may be greater when the nose is examined both before and after decongestion of the nasal mucosa 25. In addition to the Cottle manoeuvre, some authors have also used nasal dilators (e.g. Nozovent, Breathe Right) when objectifying nasal patency around the nasal valve area 26-28.

When assessing and objectifying nasal patency, it is important to consider any possible nasal valve pathology. This means distinguishing whether the measurement is made in front of or behind the nasal valve area. In our study, we used two devices to measure nasal patency: the PNIF device to measure patency in front of the nasal valve and a flowmeter to measure patency behind the nasal valve. Flowmetry is a validated device to measure nasal airflow. According to previous publications, there is a significant difference in nasal flow values between healthy individuals and patients with various degrees of nasal septal deviation and/or inferior turbinate hypertrophy 13.

Our study found a significant difference in subjective evaluation of nasal patency and PNIF values between comparable groups of patients with and without nasal valve pathology. This suggests that the device measuring nasal flow anterior to the nasal valve was able to accurately detect differences in nasal flow associated with nasal valve pathology. However, there was no significant difference in flowmetry values (i.e. measurements taken behind the nasal valve) between the groups. This was expected, since nasal valve pathology primarily affects airflow in front of the nasal cavity. Based on flowmetry values, we were able to predict whether the patients would require correction of not only the nasal valve but also the septum in a single surgical procedure. It is clear that a combination of objective measurements can provide valuable information on nasal patency and may help guide treatment decisions in patients with nasal congestion and nasal valve pathology. To our knowledge, this is the first observation of nasal patency in patients with a nasal valve pathology using two devices when taking into account the measurement site.

The limitations of our study are the small number of patients – the study includes only 26 patients and 38 nasal cavity sides. The limited sample size is due to the rarity of the pathology and strict enrolment process. Therefore, the results cannot be generalised. The benefit of the examination must thus be confirmed on a larger sample. Another limitation is the fact that the devices for flowmetry and PNIF are validated but not yet standardised. It would be beneficial to analyse the results of a larger cohort and a combination of standardised instruments, e.g. a combination of rhinomanometry and PNIF, in further observations. It would also be beneficial to establish a standardised examination procedure, including timing, since an individual result may be influenced by concurrent inferior turbinate hypertrophy caused by concurrent rhinitis or nasal cycle. Further observational studies should also investigate whether the surgical approach was changed after the use of the combined methods and whether performing both tests of nasal patency is cost-effective. Given that both flowmetry and PNIF are portable, inexpensive and rapid methods of investigation, and that functional rhinoplasty is considered a procedure with a significant impact on quality of life, we believe that it should be cost-effective.

Conclusions

To determine the proportion of the obstruction in the nasal valve area, it is appropriate to use a combination of methods measuring in the area in front of and behind the nasal valve. By combining flowmetry and PNIF, the site of obstruction can be accurately localised, thereby avoiding potential misdiagnosis and unnecessary intranasal surgery. This combination may be advantageous in the evaluation of these patients and provides important information when considering further surgical treatment.

Conflict of interest statement

The Authors declare no conflict of interest.

Funding

This research received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Author contributions

ZK: conceptualization, methodology, formal analysis, investigation, project administration, writing – original draft, writing – review & editing; VB: conceptualization, methodology, investigation, writing – original draft, writing – review & editing; JV: conceptualization, supervision; DR, PZ: investigation, data curation.

Each author of the manuscript has participated sufficiently in this work and takes public responsibility for the content of the paper. All authors have taken care to ensure the integrity of the work and their personal reputation and have approved the final version of the manuscript.

Ethical consideration

This study was approved by the ethics committee of the Hospitals of the Pardubice region (protocol number 6/2015).

The research was conducted ethically, with all study procedures being performed in accordance with the requirements of the World Medical Association’s Declaration of Helsinki.

Written informed consent was obtained from each patient for study participation and data publication.

History

Received: November 3, 2024

Accepted: February 16, 2025

Figures and tables

Figure 1. Flowmetry. Adjustment of the nasal cannula to enable measurement with the device. The part of the nasal cannula intended for insertion into the left nostril is cut off and taped over, and the measurement is then carried out for each side separately using only the part of the oxygen goggles intended for insertion into the right nostril (upper part). The nasal cannula is connected to the flowmeter, which displays the breathing pattern on the device screen. The result is the average of the resting inspiratory peaks recorded by the device (lower part).

Figure 2. Diagram of the most common nasal valve pathologies during steady state (A) and during maximal inspiration (B). I = external nasal valve collapse (bilateral, narrowing of more than 90% during maximal inspiration), II = severe septal subluxation (right-sided, more than 75% narrowing), III = wide columella (bilateral, more than 50% narrowing on each side), IV = internal nasal valve narrowing (bilateral, more than 50% narrowing).

| Nasal valve pathology | n = 19 |

|---|---|

| External nasal valve collapse | 6 |

| Severe septal subluxation | 4 |

| Wide columella | 4 |

| Internal nasal valve narrowing | 5 |

| Septal deformity (Mladina) | Nasal valve pathology (n = 19) | Without nasal valve pathology (n = 19) |

|---|---|---|

| Type 0 | 11 | 11 |

| Type 1 | 3 | 4 |

| Type 3 | 3 | 2 |

| Type 5 | 2 | 2 |

| Total (n = 38) | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Nasal valve obstructed | Nasal valve unobstructed | p value | |

| (n = 19) | (n = 19) | ||

| Age (years) | 43.6 (19-67; SD 15.5) | 49.6 (21-75; SD 16.5) | 0.299 |

| Gender (% male) | 47.4 | 47.4 | 1.000 |

| VAS of nasal patency | 4.99 (0.9-10; SD 2.77) | 8.64 (4.9-10; SD 1.28) | < 0.001 |

| Flowmetry (V) | 4.28 (3-6; SD 0.64) | 4.26 (3.2-4.8; SD 0.42) | 0.462 |

| PNIF (L/min) | 36.1 (0-70; SD 23.7) | 91.6 (35-290; SD 68.9) | 0.002 |

| SD: standard deviation; VAS: visual analogue scale; PNIF: peak nasal inspiratory flow. | |||

References

- Al Shaban K, Abdullah F. Nasal airway obstruction and the quality of life. American Scientific Research Journal for Engineering, Technology, and Sciences (ASRJETS). 2016;16:328-333.

- Shedden A. Impact of nasal congestion on quality of life and work productivity in allergic rhinitis: findings from a large online survey. Treat Respir Med. 2005;4:439-446. doi:https://doi.org/10.2165/00151829-200504060-00007

- Whyte A, Boeddinghaus R. Imaging of adult nasal obstruction. Clin Radiol. 2020;75:688-704. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.crad.2019.07.027

- Becker D, Becker S. Treatment of nasal obstruction from nasal valve collapse with alar batten grafts. J Long Term Eff Med Implants. 2003;13:259-269. doi:https://doi.org/10.1615/jlongtermeffmedimplants.v13.i3.100

- Taylor C. Evaluation of the patient with nasal obstruction. Facial Plast Surg. 2023;39:590-594. doi:https://doi.org/10.1055/a-2122-7251

- Rhee J, Weaver E, Park S. Clinical consensus statement: diagnosis and management of nasal valve compromise. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2010;143:48-59. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.otohns.2010.04.019

- Position statement: nasal valve repair. Published online 2023.

- Avashia Y, Glener A, Marcus J. Functional nasal surgery. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2022;150:439e-454e. doi:https://doi.org/10.1097/prs.0000000000009290

- Clement P. Committee report on standardization of rhino manometry. Rhinology. 1984;22:151-155.

- Clement P, Gordts F. Consensus report on acoustic rhinometry and rhinomanometry. Rhinology. 2005;43:169-179.

- Holmström M, Scadding G, Lund V. Assessment of nasal obstruction. A comparison between rhinomanometry and nasal inspiratory peak flow. Rhinology. 1990;28:191-196.

- Barnes M, Lipworth B. Removing nasal valve obstruction in peak nasal inspiratory flow measurement. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2007;99:59-60. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/s1081-1206(10)60622-9

- Knížek Z, Vodička J, Jelínek J. Měření nosní průchodnosti pomocí flowmetrie a klasifikace endoskopického obrazu nosní dutiny. Otorinolaryngol Foniatr. 2019;68:143-149.

- Knížek Z, Kotulek M, Brothánková P. Outcome of continuous positive airway pressure adherence based on nasal endoscopy and the measurement of nasal patency – A prospective study. Life (Basel). 2023;13. doi:https://doi.org/10.3390/life13010219

- Mladina R. The role of maxillar morphology in the develop ment of pathological septal deformities. Rhinology. 1987;25:199-205.

- Mladina R, Skitarelić N, Poje G. Clinical implications of nasal septal deformities. Balkan Med J. 2015;32:137-146. doi:https://doi.org/10.5152/balkanmedj.2015.159957

- Bugten V, Nilsen A, Thorstensen W. Quality of life and symptoms before and after nasal septoplasty compared with healthy individuals. BMC Ear Nose Throat Disord. 2016;16. doi:https://doi.org/10.1186/s12901-016-0031-7

- van Egmond M, Rovers M, Tillema A. Septoplasty for nasal obstruction due to a deviated nasal septum in adults: a systematic review. Rhinology. 2018;56:195-208. doi:https://doi.org/10.4193/rhin18.016

- Hismi A, Yu P, Locascio J. The impact of nasal obstruction and functional septorhinoplasty on sleep quality. Facial Plast Surg Aesthet Med. 2020;22:412-419. doi:https://doi.org/10.1089/fpsam.2020.0005

- André R, Vuyk H, Ahmed A. Correlation between subjective and objective evaluation of the nasal airway. A systematic review of the highest level of evidence. Clin Otolaryngol. 2009;34:518-525. doi:https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1749-4486.2009.02042.x

- Oleszkiewicz A, Schultheiss T, Schriever V. Effects of “trigeminal training” on trigeminal sensitivity and self-rated nasal patency. Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol. 2018;275:1783-1788. doi:https://doi.org/10.1007/s00405-018-4993-5

- Tasca I, Ceroni Compadretti G, Sorace F. Nasal valve surgery. Acta Otorhinolaryngol Ital. 2013;33:196-201.

- Das A, Spiegel J. Evaluation of validity and specificity of the Cottle maneuver in diagnosis of nasal valve collapse. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2020;146:277-280. doi:https://doi.org/10.1097/prs.0000000000006978

- Gagnieur P, Fieux M, Louis B. Objective diagnosis of internal nasal valve collapse by four-phase rhinomanometry. Laryngoscope Investig Otolaryngol. 2022;7:388-394. doi:https://doi.org/10.1002/lio2.784

- Tikanto J, Pirilä T. Effects of the Cottle’s maneuver on the nasal valve as assessed by acoustic rhinometry. Am J Rhinol. 2007;21:456-459. doi:https://doi.org/10.2500/ajr.2007.21.3040

- Gosepath J, Mann W, Amedee R. Effects of the breathe right nasal strips on nasal ventilation. Am J Rhinol. 1997;11:399-402. doi:https://doi.org/10.2500/105065897781285990

- Awan M, Ali M, Ahmed M. Clinical study on the use of nozovent in a tertiary care setting. J Pak Med Assoc. 2004;54:614-617.

- Petruson B. The importance of improved nasal breathing: a review of the Nozovent nostril dilator. Acta Otolaryngol. 2007;127:418-423. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/00016480500417106

Downloads

License

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

Copyright

Copyright (c) 2025 Società Italiana di Otorinolaringoiatria e chirurgia cervico facciale

How to Cite

- Abstract viewed - 501 times

- PDF downloaded - 101 times