Thyroid

Vol. 45: Issue 4 - August 2025

Preoperative vitamin D administration does not affect rates of post-thyroidectomy hypocalcaemia

Abstract

Objective. Hypoparathyroidism is a common complication of total thyroidectomy, and the role of vitamin D deficiency in post-thyroidectomy hypocalcaemia is unclear. This study evaluates the role of preoperative vitamin D supplementation in reducing rates of postoperative hypocalcaemia.

Methods. This is a retrospective review of patients who underwent thyroidectomy before (n = 728) and after (n = 491) introduction of the routine preoperative active vitamin D in a tertiary medical centre. Patients were monitored for calcium support efficacy in managing hypocalcaemia.

Results. Demographics, preoperative calcium levels, pathologies, and surgeries were similar between groups. Postoperative calcium levels showed a smaller decrease in the study group (-0.5 mg/dL vs -0.62 mg/dL, p = 0.04). Short-term postoperative hypocalcaemia (< 8 mg/dL) occurred in 15.7% (patients treated between 1996-2009) and 14.5% (patients treated between 2010-2016) (p = 0.54). Symptomatic and long-term hypocalcaemia rates were also comparable (p = 0.88, p = 0.6). Central neck dissection and goiter/thyrotoxicosis were significantly associated with hypocalcaemia.

Conclusions. Pre-thyroidectomy vitamin D treatment does not prevent postoperative hypocalcemia. These findings suggest individualised calcium support strategies based on patient-specific factors post-thyroidectomy.

Introduction

Temporary hypoparathyroidism (TH) is the most common complication of total thyroidectomy, ranging from 1% to 50% and even as high as 83% 1. While permanent hypoparathyroidism (longer than 6 months after the surgery) is a less common complication occurring in 1-9% of total thyroidectomy cases 2,3, its long-term impact can be severe, including chronic renal failure, cardiovascular morbidity, and eventually higher mortality rate 4-6. The hallmark of postsurgical hypoparathyroidism is neuromuscular irritability due to acute hypocalcaemia. Significant hypocalcaemia may result in severe tetany, laryngospasm, seizures and cardiac arrhythmias 7. Severe symptomatic hypocalcaemia may be associated with the need for additional medication, either intravenous or by oral administration, prolonged hospitalisation, high rates of readmission, low quality of life and increased costs to both patients and the healthcare system.

Several publications have identified risk factors for post-operative hypoparathyroidism and hypocalcaemia including central or lateral neck dissection 8-11, malignancy as indication for the surgery 2,11, female gender 8,11 and a decrease in parathyroid hormone level at postoperative day 1 6,8,12.

Several studies have attempted to determine whether vitamin D levels prior to total thyroidectomy can predict the risk for hypocalcaemia. The results have been somewhat conflicting, with studies showing no association between low preoperative vitamin D level and postoperative hypocalcaemia 13-15 and other publications demonstrating an association 3,10,11,16,17.

Assuming that preoperative low vitamin D level is indeed associated with postoperative hypocalcaemia, a further question is whether preoperative treatment with vitamin D with or without calcium supplement can potentially decrease the risk of postoperative hypocalcaemia among patients undergoing total thyroidectomy with or without neck dissection. While several studies have demonstrated a reduced risk of hypocalcaemia with preoperative vitamin D treatment 18-20, others did not show any effect 21.

This study aims to evaluate the necessity of vitamin D supplementation in preventing hypocalcaemia post-thyroidectomy. We performed a case-control study comparing postoperative hypocalcaemia rates at our institution during a period in which patients underwent total thyroidectomy without any preoperative active vitamin D supplementation and a subsequent period during which all patients received preoperative active vitamin D prior to undergoing total thyroidectomy or completion thyroidectomy. This study particularly examines whether specific subgroups − such as those undergoing central neck dissection or those with goiter or Graves’ disease as indications for surgery − might derive greater benefits from this preoperative supplementation.

Materials and methods

Study design and subjects

This case-control study reviewed electronic health records from Rabin Medical Centre, a tertiary university-affiliated medical centre. The study involved 2 distinct groups: patients undergoing thyroidectomy between 1996 and 2009 without routine preoperative vitamin D, and patients from 2010 to 2016 who were administered preoperative vitamin D based on the updated institutional protocol. Our case group comprised patients who underwent either total thyroidectomy or staged (completion) thyroidectomy and received preoperative active vitamin D treatment starting in 2010. Patients included in the control group underwent thyroidectomy from 1996 to 2009, during which preoperative vitamin D supplementation was not part of standard practice. Patients in the case group from 2010 to 2016 were assessed for potential preoperative vitamin D supplementation. Both groups included patients who underwent central compartment and lateral neck dissections. Near-total thyroidectomy procedures were not included in this cohort as they are not routinely done in our institute.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

Patients (aged 18 years or older) who underwent thyroid surgery between 1996 and 2016 were included in this study. Patients who were lithium users, those with known malabsorptive conditions, parathyroid diseases, or those treated with radiation therapy to the neck were excluded.

Data collection

The data extracted from patient files included demographics, medical history, indications for surgery, type of operation performed, pathology reports, and pre- and postoperative serum calcium and albumin levels. Follow-up and outcomes were also recorded. The primary comparison was between the case and control groups regarding the incidence of postoperative hypocalcaemia.

Preoperative active vitamin D treatment

Beginning in 2010, a new protocol was introduced where the administration of Alfacalcidol (0.5 mcg twice daily for 5 days preoperatively) was considered for patients undergoing thyroidectomy, aiming to assess its impact on postoperative hypocalcaemia. This intervention defines our case group, compared against a control group that underwent thyroid surgery from 1996 to 2009 without preoperative vitamin D treatment.

Thyroid surgery and postoperative care

All surgeries were performed by fellowship-trained senior head and neck surgeons, with high surgical volume of 100-250 thyroid operations per year. Patients were hospitalised for a minimum of 3 days after surgery.

Calcium and albumin blood levels were routinely tested on postoperative days 1 and 3. Symptomatic hypocalcaemia was defined in patients with reported signs and symptoms suggestive of postoperative hypocalcaemia and in patients who needed intravenous treatment of calcium gluconate. These patients were treated with doses of intravenous calcium gluconate until the symptoms resolved and increased doses of oral active vitamin D (0.5 mcg BID) and calcium carbonate (1gm QID) until hypocalcaemia resolved.

Short-term hypocalcaemia was defined as albumin corrected calcium < 8 mg/dL that resolved within one month of thyroidectomy. All patients underwent an examination 6 months after surgery, including calcium level. Long-term hypocalcaemia was defined as albumin corrected calcium < 8 mg/dL lasting at least 6 months after surgery.

Statistical analysis

All statistical analyses were performed using IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows, Version 28.0 (IBM Corp, Armonk, NY, USA). Associations between 2 categorical variables were examined using χ2 test and Fisher’s exact test; associations between continuous and quantitative variables were examined using Student’s T-Test for normally distributed data, and Mann-Whitney U-Test as a nonparametric alternative. Normality was assessed using Kolmogorov-Smirnov test. A two-sided p value of < 0.05 was considered statistically significant for all analyses.

Results

The study included 1,219 patients with a mean age of 49.3+8.9 years. The operative procedures included total or near-total thyroidectomy (n = 989, 81.1%) and staged thyroidectomy (n = 139, 11.4%). Total thyroidectomy with concomitant central compartment neck dissection was performed in 91 patients (7.5%). We compared postoperative outcomes between 491 patients treated under a standardised preoperative vitamin D protocol (2010-2016) and 728 patients who underwent surgery before its implementation (1996-2009). A comparison of the baseline characteristics between the groups is shown in Table I. Except for a significantly higher mean age among the control group, other parameters including types of surgery, concomitant neck dissection, and pathologic findings did not differ significantly between groups.

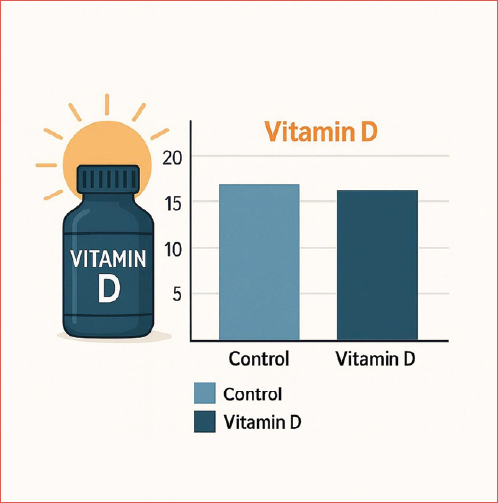

Mean preoperative calcium levels were 9.4 ± 0.6 mg/dL in the study group and 9.5±0.7 mg/dL in the control group (p = 0.47; RR = 0.95, 95% CI 0.61 to 1.35). Postoperatively, the calcium levels decreased more in the control group (mean, 8.78 ± 0.768 mg/dL; Δ = -0.62 ± 0.985 mg/dL) than the study group (mean, 9.0 ± 0.755 mg/dL; Δ = -0.5 ± 1.024 mg/dL). When comparing the magnitude of change between the 2 groups (Δ), the study group demonstrated a significantly smaller decline in calcium levels compared to the control group (p = 0.04). Short-term postoperative hypocalcaemia was observed in 14.5% of patients following the standardised vitamin D protocol (2010-2016), compared to 15.7% in the pre-implementation group (1996-2009) (p = 0.54; RR = 0.92, 95% CI 0.70 to 1.21). There were no significant between-group differences in the rate of short-term postoperative hypocalcaemia, overall or in subgroup analyses for age and gender. The difference in the rate of short-term hypocalcaemia between the study and control group remained nonsignificant even after adjusting for the type of surgery (Cover figure and Table II) and type of pathology (Tab. III). The incidence of symptomatic hypocalcaemia remained consistent between the 2 groups, suggesting that the standardised vitamin D protocol did not significantly alter outcomes, as in the study group 18 patients of 71 patients with hypocalcaemia had symptoms (25.3%), and in the control group 30 patients of 114 patients with hypocalcaemia were symptomatic (26.3%), with a p value of 0.88.

The risk of short-term hypocalcaemia was significantly higher in patients who underwent total thyroidectomy plus central neck dissection than in patients treated by thyroidectomy alone (p < 0.0001; RR=3.42, 95% CI 2.59 to 4.51). The risk was also significantly higher in patients with pathologic findings of goiter (p = 0.0011; RR=1.64, 95% CI 1.22 to 2.21) and thyrotoxicosis (p = 0.03; RR=1.54, 95% CI 1.04 to 2.27) compared to patients with benign or malignant nodules.

Long-term hypocalcaemia rates were 4.2% under the standardised vitamin D protocol and 3.9% prior to its implementation. There was no significant between-group difference in the rate of long-term postoperative hypocalcaemia (p = 0.60; RR=0.95, 95% CI 0.67 to 1.32). The 2 groups were similar for mean age, gender ratio, types of pathology, and surgery. As shown in Table IV, the risk of long-term hypocalcaemia was significantly higher in patients after total thyroidectomy and central neck dissection (13/91, 14.2%) than in patients with other type of surgeries (p < 0.0001; RR = 4.48, 95% CI 2.46 to 8.13). It was also significantly higher in patients with goiter (17/261, 6.5%) than in patients with other pathologies (p = 0.04; RR = 1.78, 95% CI 1.02 to 3.13).

Discussion

Our comparative analysis suggests that the introduction of a standardised preoperative vitamin D protocol did not significantly alter the rates of postoperative hypocalceamia. Although our study population showed a smaller decrease in calcium levels postoperatively compared to the control group, with a difference of 0.1 mg/dL, this change was not clinically relevant. The rates of postoperative hypocalcaemia, both symptomatic and laboratory-confirmed, remained the same between both groups. Even so, the significant difference between the 2 groups may suggest that higher doses of preoperative vitamin D and calcium support could be associated with a clinically significant reduction of postoperative hypocalcaemia among thyroidectomy patients. Further trials to study this subject are clearly warranted.

The lack of difference in the hypocalcaemia rate between patients treated with preoperative vitamin D and calcium support and patients without supplementation remains consistent even in high-risk subgroups, such as those undergoing thyroidectomy with central neck dissection or for pathologies like goiter or Graves’ disease. The higher incidence of postoperative hypocalcaemia in these groups aligns with previous studies 11, underscoring the heightened surgical risks but showing no additional benefit from preoperative vitamin D supplementation.

Central neck dissection is well-recognised as a risk factor for hypocalcaemia due to its potential impact on the vascular supply of the parathyroid glands 11. Our findings, similar to those of Chen et al. 11, support this association but do not demonstrate a mitigating effect of vitamin D supplementation in these cases. Furthermore, the association between substernal goiter and increased postoperative hypocalcaemia risk, consistent with the prior literature, highlights the importance of tailored postoperative calcium management rather than reliance on standardised preoperative vitamin D protocols.

The association between preoperative vitamin D blood levels and postoperative hypocalcaemia was also studied extensively by several authors, with conflicting results. While some authors, such as Vibhatavata et al. 17, found that preoperative vitamin D deficiency (< 20 ng/mL) significantly increased the risk of symptomatic hypocalcaemia after thyroidectomy, others, including Godazandeh et al. 14, observed no correlation between vitamin D status and postoperative calcium levels. Similarly, Martín-Román et al. 15 reported that patients with lower preoperative vitamin D levels exhibited faster recovery from postoperative hypocalcaemia, suggesting a potential preconditioning effect of deficiency, allowing the parathyroid glands to recover more efficiently and quickly after the insult they experience during total thyroid surgery. These discrepancies highlight the complexity of vitamin D’s role in calcium homeostasis and its impact on surgical outcomes

Our approach − uniform supplementation without stratifying by baseline vitamin D levels − did not yield significant improvements in hypocalcaemia outcomes. This aligns with findings by Donahue et al. 22, who conducted a randomised controlled trial and observed no significant reduction in hypocalcaemia rates with preoperative supplementation. Likewise, Vendrig et al. 21 demonstrated that calcitriol prophylaxis in children undergoing thyroidectomy had minimal impact on preventing postoperative hypocalcaemia.

Notably, a subset of studies suggests potential benefits of vitamin D supplementation in preventing symptomatic and laboratory hypocalcaemia. Nemade et al. 18 showed that combined calcium and vitamin D supplementation significantly reduced both laboratory and symptomatic hypocalcaemia rates. Jaan et al. 20 further supported these findings, reporting a marked decrease in the incidence of hypocalcaemia when supplementation was initiated preoperatively and continued postoperatively. However, these results were not replicated in larger, more diverse cohorts 23,24, suggesting that patient selection and protocol design may heavily influence outcomes. Such variability underscores the need for robust, multicentre randomised trials to establish definitive guidelines and identify the patients that are most likely to benefit from supplementation.

The limitations of our study include its retrospective nature and its restriction to a single institution, which may affect the generalisability of the findings. Furthermore, the lack of routine pre- and postoperative PTH and vitamin D level measurements, since these are not routinely measured, restricts our ability to assess the direct biochemical impact of active vitamin D supplementation on calcium metabolism and its differential effects based on patients’ vitamin D status. Additionally, we encourage future studies to investigate the specific effects of preoperative vitamin D under different clinical scenarios. While completion thyroidectomies were included in this study, their small proportion in both cohorts and the lack of significant differences in hypocalcaemia rates across surgery types suggest minimal impact on our findings. Despite these limitations, our study is one of the largest cohorts to explore the role of preoperative vitamin D treatment in thyroid surgery, contributing valuable insights into this complex topic.

Conclusions

The administration of active vitamin D before thyroidectomy does not seem to have a preventive effect on postoperative short-term laboratory or symptomatic hypocalcaemia, or on long-term hypocalcaemia. Given that our findings did not indicate any advantage for preoperative supplementation and considering that results from other trials are somewhat inconclusive, we believe it is not possible to make a definitive recommendation for preoperative treatment. Therefore, we advocate the need for further prospective randomised trials to establish clear guidelines for preoperative treatment in individuals undergoing total thyroidectomy.

Conflict of interest statement

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Funding

This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Author contributions

EY, UA: conceived and designed the study; AR, DD: provided statistical advice on study design and analyzed the data; EY, DD: drafted the manuscript, and all authors contributed substantially to its revision; EY: takes responsibility for the paper as a whole.

Ethical consideration

This study was approved by the Institutional Ethics Committee of Rabin Medical Center (approval number RMC-12-0262).

The research was conducted ethically, with all study procedures being performed in accordance with the requirements of the World Medical Association’s Declaration of Helsinki.

Written informed consent was waivered by the Institutional Review Board due to the retrospective nature of the study.

History

Received: November 16, 2024

Accepted: January 4, 2025

Figures and tables

| Study group | Control group | p value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| N = 491 | N =728 | ||

| Age (years) | 46.2 ± 7.7 | 51.3 ± 9.5 | 0.01 |

| Gender (male) | 149 (30.3%) | 244 (33.5%) | 0.25 |

| Surgery | |||

| Total thyroidectomy | 386 (78.6%) | 603 (82.8%) | 0.07 |

| Completion thyroidectomy | 64 (13%) | 75 (10.3%) | 0.14 |

| Total thyroidectomy with central neck dissection | 41 (8.4%) | 50 (6.9%) | 0.33 |

| Pathology | |||

| Malignancy | 292 (59.5%) | 414 (56.9%) | 0.37 |

| Goiter | 101 (20.6%) | 160 (22%) | 0.56 |

| Thyrotoxicosis | 46 (9.4%) | 88 (12.1%) | 0.14 |

| Benign | 42 (8.6%) | 48 (6.6%) | 0.2 |

| Unknown | 10 (2%) | 18 (2.5%) | 0.62 |

| *All values are presented as n (%). | |||

| Type of surgery | Study group | Control group | Statistical analysis |

|---|---|---|---|

| N = 71/491 | N = 114/728 | ||

| Total thyroidectomy | 12.7% | 13.9% | p = 0.58 |

| (N = 49/386) | (N = 84/603) | OR = 0.9 | |

| 95% CI: 0.62-1.31 | |||

| Completion thyroidectomy | 7.8% | 9.3% | p = 0.75 |

| (N = 5/64) | (N = 7/75) | OR = 0.82 | |

| 95% CI: 0.25-2.73 | |||

| Total thyroidectomy + central neck dissection | 41.5% | 46% | p = 0.66 |

| (N = 17/41) | (N = 23/50) | OR = 0.83 | |

| 95% CI: 0.36-1.91 | |||

| CI: confidence interval; OR: odds ratio. | |||

| Type of pathology | Study group | Control group | Statistical analysis |

|---|---|---|---|

| N = 71/491 | N = 114/728 | ||

| Malignancy | 12.3% | 14% | p = 0.52 |

| (N = 36/292) | (N = 58/414) | OR = 0.86 | |

| 95% CI: 0.55-1.35 | |||

| Goiter | 22.8% | 19.4% | p = 0.51 |

| (N = 23/101) | (N = 31/160) | OR = 1.23 | |

| 95% CI: 0.66-2.25 | |||

| Thyrotoxicosis | 17.4% | 21.6% | p = 0.56 |

| (N = 8/46) | (N = 19/88) | OR = 0.76 | |

| 95% CI: 0.31-1.91 | |||

| Benign | 7.1% | 8.3% | p = 1 |

| (N = 3/42) | (N = 4/48) | OR = 0.85 | |

| 95% CI: 0.18-4.02 | |||

| Unknown | 10% | 11.1% | p = 1 |

| (N = 1/10) | (N = 2/18) | RR = 0.88 | |

| 95% CI: 0.07-11.22 | |||

| CI: confidence interval; OR: odds ratio. | |||

| Type of surgery/pathology | Patients |

|---|---|

| N = 50/1219 | |

| Type of surgery | |

| Total thyroidectomy | 2.9%, N = 29/986 |

| Completion thyroidectomy | 5.7%, N = 8/139 |

| Total thyroidectomy + central neck dissection | 14.2%, N = 13/91 |

| Type of pathology | |

| Malignancy | 3.9%, N = 28/706 |

| Goiter | 6.5%, N = 17/261 |

| Thyrotoxicosis | 3.7%, N = 5/134 |

| Benign | 0%, N = 0/90 |

References

- Abboud B, Sleilaty G, Zeineddine S. Is therapy with calcium and vitamin D and parathyroid autotransplantation useful in total thyroidectomy for preventing hypocalcemia?. Head Neck. 2008;30:1148-54. doi:https://doi.org/10.1002/hed.20836

- Riordan F, Murphy M, Feeley L. Association between number of parathyroid glands identified during total thyroidectomy and functional parathyroid preservation. Langenbecks Arch Surg. 2022;407:297-303. doi:https://doi.org/10.1007/s00423-021-02287-6

- Rosato L, Avenia N, Bernante P. Complications of thyroid surgery: analysis of a multicentric study on 14,934 patients operated on in Italy over 5 years. World J Surg. 2004;28:271-276. doi:https://doi.org/10.1007/s00268-003-6903-1

- Bergenfelz A, Nordenström E, Almquist M. Morbidity in patients with permanent hypoparathyroidism after total thyroidectomy. Surgery. 2020;167:124-128. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.surg.2019.06.056

- Ponce De León-Ballesteros G, Bonilla-Ramírez C, Hernández-Calderón F. Mid-Term and long-term impact of permanent hypoparathyroidism after total thyroidectomy. World J Surg. 2020;44:2692-2698. doi:https://doi.org/10.1007/s00268-020-05531-0

- Almquist M, Ivarsson K, Nordenström E. Mortality in patients with permanent hypoparathyroidism after total thyroidectomy. Br J Surg. 2018;105:1313-1318. doi:https://doi.org/10.1002/bjs.10843

- Bilezikian J, Khan A, Potts J. Hypoparathyroidism in the adult: Epidemiology, diagnosis, pathophysiology, target-organ involvement, treatment, and challenges for future research. J Bone Mineral Res. 2011;26:2317-2337. doi:https://doi.org/10.1002/jbmr.483

- Păduraru D, Ion D, Carsote M. Post-thyroidectomy hypocalcemia - risk factors and management. CHR. 2019;114. doi:https://doi.org/10.21614/chirurgia.114.5.564

- Wu S, Chiang Y, Fisher S. Risks of hypoparathyroidism after total thyroidectomy in children: a 21-year experience in a highvolume cancer center. World J Surg. 2020;44:442-451. doi:https://doi.org/10.1007/s00268-019-05231-4

- Yu Y, Fallon S, Carpenter J. Perioperative determinants of transient hypocalcemia after pediatric total thyroidectomy. J Pediatr Surg. 2017;52:684-688. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpedsurg.2017.01.011

- Chen Z, Zhao Q, Du J. Risk factors for postoperative hypocalcaemia after thyroidectomy: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Int Med Res. 2021;49. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/0300060521996911

- Cayo A, Yen T, Misustin S. Predicting the need for calcium and calcitriol supplementation after total thyroidectomy: results of a prospective, randomized study. Surgery. 2012;152:1059-1067. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.surg.2012.08.030

- Ravikumar K, Sadacharan D, Muthukumar S. A prospective study on role of supplemental oral calcium and Vitamin D in prevention of postthyroidectomy hypocalcemia. Indian J Endocr Metab. 2017;21. doi:https://doi.org/10.4103/ijem.ijem_402_16

- Godazandeh G, Kashi Z, Godazandeh F. Influence of thyroidectomy on postoperative serum calcium level regarding serum vitamin D status. A prospective study. Caspian J Intern Med. 2015;6:72-76.

- Martín-Román L, Colombari R, Fernández-Martínez M. Vitamin D deficiency reduces postthyroidectomy protracted hypoparathyroidism risk. Is gland preconditioning possible?. J Endocr Soc. 2022;7. doi:https://doi.org/10.1210/jendso/bvac174

- Zhang Y, Zheng W, Huang Y. Vitamin D insufficiency predicts susceptibility of parathyroid hormone reduction after total thyroidectomy in thyroid cancer patients. Int J Endocrinol. 2021;2021:1-7. doi:https://doi.org/10.1155/2021/8657918

- Vibhatavata P, Pisarnturakit P, Boonsripitayanon M. Effect of preoperative vitamin D deficiency on hypocalcemia in patients with acute hypoparathyroidism after thyroidectomy. Int J Endocrinol. 2020;2020:1-9. doi:https://doi.org/10.1155/2020/5162496

- Nemade S, Rokade V, Pathak N. Comparison between perioperative treatment with calcium and with calcium and vitamin D in prevention of post thyroidectomy hypocalcemia. Indian J Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2014;66:214-219. doi:https://doi.org/10.1007/s12070-011-0430-4

- Oltmann S, Brekke A, Schneider D. Preventing postoperative hypocalcemia in patients with Graves disease: a prospective study. Ann Surg Oncol. 2015;22:952-958. doi:https://doi.org/10.1245/s10434-014-4077-8

- Jaan S, Sehgal A, Wani R. Usefulness of pre- and post-operative calcium and Vitamin D supplementation in prevention of hypocalcemia after total thyroidectomy: a randomized controlled trial. Indian J Endocr Metab. 2017;21. doi:https://doi.org/10.4103/2230-8210.195997

- Vendrig L, Mooij C, Derikx J. The effect of pre-thyroidectomy calcitriol prophylaxis on post-thyroidectomy hypocalcaemia in children. Horm Res Paediatr. 2022;95:423-429. doi:https://doi.org/10.1159/000525626

- Donahue C, Pantel H, Yarlagadda B. Does preoperative calcium and calcitriol decrease rates of post-thyroidectomy hypocalcemia? A randomized clinical trial. J Am Coll Surg. 2021;232:848-954. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2021.01.016

- Khatiwada A, Harris A. Use of pre-operative calcium and vitamin D supplementation to prevent post-operative hypocalcaemia in patients undergoing thyroidectomy: a systematic review. J Laryngol Otol. 2021;135:568-573. doi:https://doi.org/10.1017/S0022215121001523

- Casey C, Hopkins D. The role of preoperative vitamin D and calcium in preventing post-thyroidectomy hypocalcaemia: a systematic review. Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol. 2023;280:1555-1563. doi:https://doi.org/10.1007/s00405-022-07791-z

Downloads

License

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

Copyright

Copyright (c) 2025 Società Italiana di Otorinolaringoiatria e chirurgia cervico facciale

How to Cite

- Abstract viewed - 923 times

- PDF downloaded - 164 times