Audiology

Vol. 45: Issue 6 - December 2025

Neurovascular compression and vestibular compromises in idiopathic sudden sensorineural hearing loss

Abstract

Objective. This study aimed to investigate the association between vestibular impairment and neurovascular compression at cerebellopontine angle (CPA) and internal auditory canal (IAC) in patients with idiopathic sudden sensorineural hearing loss (ISSNHL).

Methods. Seventy-one ISSNHL patients underwent audio-vestibular tests and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of CPA-IAC. The MRI findings of both ears were graded by Chavda, Gorrie and Kazawa systems.

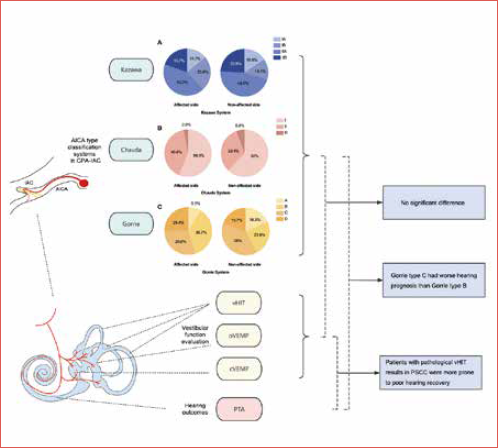

Results. No significant association was found between different neurovascular types and the results of caloric test, vestibular evoked myogenic potentials and video head impulse test (vHIT). Chavda type II was more common in ISSNHL patients with vertigo. Tinnitus, initial and outcome hearing threshold showed no significant differences among different neurovascular types. ISSNHL patients with Gorrie type C had worse hearing prognosis than those with type B. ISSNHL patients with pathological vHIT results in the posterior semicircular canal were more prone to poor hearing recovery.

Conclusions. Vestibular testing results and radiological neurovascular compression signs in CPA-IAC region may not be associated in ISSNHL patients. Vestibular impairment is more closely related to hearing outcomes than neurovascular compression.

Introduction

Sudden sensorineural hearing loss (SSNHL) is defined as a rapid onset of sensorineural hearing loss more than 30 dB on at least three consecutive frequencies within 72 hours 1. SSNHL of unknown aetiology is known as idiopathic SSNHL (ISSNHL). The aetiological hypotheses of ISSNHL include ischaemia, viral inflammation, auto-immune disease, metabolic disorder, trauma, inner ear anomaly and others 2. About 30% of ISSNHL patients are reported to be accompanied by vertigo 3. Previous studies have shown that vertigo symptoms or vestibular impairment are associated with hearing outcomes in ISSNHL patients, even though the mechanism remains unclear 4-7.

The cerebellopontine angle (CPA) is a triangular-shaped space located anterolaterally at the junction of the pons and cerebellum. The internal auditory canal (IAC) ascends anterolaterally from the CPA and extends to the cochlea and vestibular organs. The cochleovestibular nerve (CVN) reaches CPA through IAC, and then enters the cranium, and is responsible for hearing and balance. The CPA also contains the anterior inferior cerebellar artery (AICA), which traverses close to the CVN. The labyrinthine artery, from which the AICA branches, is the only vascular supply to the labyrinth. The anatomical shape and location of the AICA is variable in CPA and IAC space. Neurovascular compression has been proposed to explain the pathophysiological mechanism leading to hemifacial spasm and trigeminal neuralgia 8. However, the vascular compression of the CVN resulting in neurotological symptoms, such as sensorineural hearing loss, vertigo, and tinnitus, remains controversial 9. Previous studies analysed the association between neurovascular compression and the affected side, audiological characteristics, concomitant symptoms and treatment outcomes of ISSNHL patients 10-13. The damaged vestibular end organs are anatomically related to the neurovascular distribution in the inner ear. Therefore, these results may provide a clue to explore the aetiology in ISSNHL patients.

The AICA gives off the labyrinthine artery into the IAC. The labyrinthine artery divides into two branches, the anterior vestibular artery (AVA) and the common cochlear artery (CCA). The former supplies the anterior semicircular canal (ASCC), horizontal semicircular canal (HSCC), utricle and the upper portion of the saccule, while the latter supplies the posterior semicircular canal (PSCC), the inferior saccular macula, and the cochlea. Recent advances have shown that the video head impulse test (vHIT) can assess the function of six semicircular canals separately, while the vestibular evoked myogenic potentials (VEMPs) can evaluate the utricle and saccule. Therefore, for patients with ISSNHL, it makes sense to explore whether neurovascular compression signs are the cause, or a biomarker, of vestibular apparatus impairment based on vestibular test results which can evaluate vestibular function objectively and locate the involved vestibular end organs.

In this retrospective study, three imaging classification systems (Kazawa, Chavda and Gorrie systems) were used to analyse the neurovascular relationship between CVN and AICA in ISSNHL patients. We aimed to explore: (1) the potential association between neurovascular compression and vestibular impairments in ISSNHL patients; (2) the significance of neurovascular compression and vestibular impairment in predicting hearing prognosis of ISSNHL patients (Cover figure).

Materials and methods

Subjects

This retrospective study was conducted in Union Hospital affiliated to Tongji Medical College, Huazhong University of Science and Technology, Wuhan, China.

According to the clinical practice guidelines for sudden hearing loss proposed by the American Academy of Otolaryngology-Head and Neck Surgery (AAO-HNS) in 2019 1, ISSNHL is defined as a hearing loss of ≥ 30 dB occurring within 72 hours, with at least three consecutive frequencies affected. Exclusion criteria were: (1) bilateral ISSNHL; (2) Meniere’s disease or recurrent sensorineural hearing loss; (3) inner ear malformation; (4) retrocochlear diseases (internal auditory stenosis, vestibular schwannoma, etc.); (5) recent history of auditory trauma or head trauma; (6) central nervous system disease (stroke, migraine, etc.); (7) history of ototoxic drug use and (8) severe systemic disease (e.g. malignant tumours). Patients younger than 18 years were also excluded.

Methods

AUDIO-VESTIBULAR EVALUATIONS

All patients completed hearing and vestibular tests within the same day at their initial visit.

PURE TONE AUDIOMETRY

After ruling out middle ear lesions through otological and tympanometry testing, a pure tone audiometry test with a frequency of 0.25 to 8 kHz was performed in a soundproof cabin. The pure tone average (PTA) was calculated as the simple arithmetic mean over 6 frequencies of 0.25, 0.5, 1, 2, 4 and 8 kHz 13. In this study, the initial pure-tone audiometry curves were divided into four types: (1) low-frequency hearing loss (the average threshold from 0.25 to 0.5 kHz was 20 dB higher than the average threshold from 4 to 8 kHz); (2) high-frequency hearing loss (the average threshold from 4 to 8 kHz was 20 dB higher than average threshold from 0.25 to 0.5 kHz); (3) flat-type hearing loss (approximated thresholds observed across the frequency range, and hearing thresholds not exceeding 90 dB HL); and (4) profound hearing loss (the average threshold at 0.5, 1, 2, and 4 kHz exceeding 90 dB HL).

CALORIC TEST

Infrared videonystagmography (Visual Eyes VNG, Micromedical Technologies, Chatham, IL) was used for caloric test. The patient lay supine with the upper trunk elevated 30°. Alternating cold (24°C) and warm (50°C) air stimulation was delivered to each external auditory canal, and the maximum slow phase velocity (SPVmax) of caloric nystagmus was measured after each stimulation. Canal paresis (CP) values were calculated by Jongkees’ formula. Unilateral vestibular hypofunction was defined as interaural asymmetry ≥ 25% in caloric nystagmus. Bilateral vestibular hypofunction was considered if SPVmax was less than 6°/s in each ear after stimulation or if the sum of SPVmax for all four stimulation conditions was less than 20°/s.

VEMPs

Cervical VEMP (cVEMP) and ocular VEMP (oVEMP) were recorded using the Eclipse system (Interacoustics A/S, Middelfart, Denmark). During the cVEMP test, patients rotated head contralaterally to activate the ipsilateral sternocleidomastoid muscle (SCM). Two active electrodes were placed on the upper third of the SCM. A ground electrode was attached to the forehead, with a reference electrode to the sternoclavicular junction. Air-conducted sound (ACS) tone bursts (500 Hz, 100 dB nHL, 5 ms, rise-plateau-fall time = 2-1-2 ms) were delivered monophonically through earphone. At least 100 stimuli were averaged during each trial. Biphasic waveforms (p13-n23) were recorded and analysed. These cVEMP results would be considered pathological in case of: (1) amplitude asymmetry rate (AR) greater than the mean of normal range ± 2 standard deviations (SD) (AR ≥ 36% in our clinic); (2) the amplitude of p13-n23 waveforms were absent or reduced. For the oVEMP test, patients were directed to maintain gaze on a fixed target at an approximately 30° degree above the horizontal plane. Two active electrodes were placed on the contralateral inferior oblique muscle. A ground electrode was attached to the forehead and a reference electrode to the chin. The stimuli in oVEMP were identical to those in cVEMP. Recording and analysis of biphasic waveforms (n10-p15) were conducted. Abnormal oVEMP responses were defined as: (1) no reliable oVEMP response after at least 50 stimuli; (2) amplitude AR greater than the mean of normal range ± 2 SD (AR ≥ 40% in our clinic).

vHIT

The vHIT was performed using the ICS Impulse system (GN Otometrics, Denmark). Patients wore a pair of lightweight goggles in order to record and analyse the eye movements. During the test, patients were asked to maintain gaze at a stationary visual target on the wall 1.0 m away. The technician stood behind the patient and manually delivered 20 to 25 passive, unpredictable and random head impulses (duration: 150-200 ms, amplitude: 5~15°, peak velocity: 150~250°/s). Corrective saccades with a velocity exceeding 50°/s were considered significant. In this study, pathological vHIT refers to a horizontal vHIT gain < 0.8, or a vertical vHIT < 0.7, accompanied by the presence of corrective saccades.

RADIOLOGICAL EVALUATIONS

All imaging examinations of ISSNHL patients were performed within one week after initial visit. MRI examinations were performed using the Verio or Magnetom Trio 3T scanner (Siemens, Erlangen, Germany) with a 12-element phased array coil. T1- and T2-weighted spin-echo imaging was used to rule out retrocochlear lesions and pathology in CPA. Three-dimensional sampling with optimised contrast and the application of different flip angle evolution (3D-SPACE) was used for: (1) studying the course of AICA and the relationship between AICA and surrounding structures, (2) excluding inner ear malformation. The parameters of the MRI sequences are shown in Supplementary Table I.

All MRI data were transferred to a workstation and imaging analyses were performed on a picture archiving and communication system (PACS) workstation (Carestream Client, Carestream Health). The MRI data of all patients were intermixed and reviewed by two senior neuroradiologists (L.P with more than ten years of experience and C.C with more than 5 years of experience) who were blinded to the clinical data. This study adopted Chavda 14, Gorrie 15 and Kazawa 16 classification systems. A detailed description of these systems is shown in Table I. Typical examples of AICA variants assessed by the Kazawa, Chavda and Gorrie systems are seen in Figures 1, 2 and 3, respectively.

TREATMENT AND OUTCOMES

All patients with ISSNHL received oral prednisolone at a dose of 60 mg per day for 6 days, then tapered to 30, 20, 10, and 5 mg for 2 days at each dose. Patients weighing less than 60 kg were initially given prednisolone at a dose of 1 mg/kg per day and gradually tapered. Patients were also given thrombolytic agents (fibrinolytic enzyme) and vasoactive drugs (ginkgo biloba extract or alprostadil). Intratympanic injection of dexamethasone (twice a week for 2 weeks) or hyperbaric oxygen therapy would be recommended if hearing did not improve after 2 weeks of conservative treatment.

Based on the Clinical Practice Guidelines for ISSNHL 1, the patients whose hearing gain (PTA change in decibels) was less than 15 dB were defined as treatment non-responders (NR), whereas patients with hearing gain more than 15 dB were considered treatment responders. The treatment responders were further divided into three groups: (1) recovery less than 50% of the maximum possible recovery (poor recovery, PR); (2) recovery to at least 50% of maximum possible recovery (good recovery, GR); (3) recovery to within 10 dB of hearing level in the non-affected ear (complete recovery, CR). Maximum possible recovery was defined as reaching the hearing level of the non-affected ear, which was regarded as the baseline for normal hearing.

Statistics analysis

Statistical analyses were performed using the software SPSS (version 26.0.0.2). All continuous variables are presented as means ± SD or median and interquartile range (IQR, 25th to 75th percentiles) after verification of normal distribution. Categorical variables are presented as counts and percentages. The chi-square test was used to compare the distribution of qualitative data. If a significant difference was found in the overall comparison, pairwise comparison with Bonferroni correction was subsequently performed to determine which two groups differed significantly. Quantitative data with normal distribution were compared by one-way analysis of variance, and quantitative data with non-normal distribution were compared by non-parametric Kruskal-Wallis test. The McNemar-Bowker test was used to compare the imaging classification results between the affected and the unaffected side. The ordinal logistic regression model was established with clinical outcome as the dependent variable and the results of caloric test, VEMPs and vHIT as independent variables respectively. The criterion for statistical significance was set at p < 0.05.

Results

Demographic characteristics

Seventy-one patients with unilateral ISSNHL were enrolled in this study. There were 34 males (47.9%) and 37 females (52.1%), and the average age was 42.4 ± 12.5 years. The right ear was involved in 27 cases (38%) and the left in 44 (62%). The median course of disease was 7 (IQR 3,14) days. Table II shows detailed demographic characteristics in patients classified based on the Kazawa, Chavda and Gorrie classification systems. No differences in age, gender, course duration or affected side were found between patients with different anatomic variations of AICA loop graded by the Kazawa, Chavda, and Gorrie classification systems respectively.

Interaural comparison of imaging classification results in unilateral ISSNHL patients

As for the Kazawa classification, type IIA was the most prevalent (30/71, 42.3%), followed by type IB (17/71, 23.9%), type IIB (14/71, 19.7%) and type IA (10/71, 14.1%). Regarding the Chavda classification, type I was the most frequent (40/71, 56.3%), followed by type II (29/71, 40.8%) and type III (2/71, 2.8%). When it comes to the Gorrie classification, type B was the most common type (26/71, 36.6%), followed by type C (21/71, 29.6%), type D (18/71, 25.4%) and type A (6/71, 8.5%). The detailed classification results of the affected and non-affected side are shown in Figure 4, and there was no significant interaural difference in the type of distribution respectively (p = 0.607, p = 0.463 and p = 0.253).

Relationship between symptoms and hearing outcomes and imaging classification results

In the entire series, 64 patients (90.1%) had tinnitus and 41 (57.7%) had vertigo. The specific distribution in each classification system is shown in Table III. When classified by the Chavda system, there were significantly more type I cases and less type II cases in patients without vertigo than in patients with vertigo (χ2 = 7.955, p = 0.012). The median initial hearing threshold of all patients was 86.7 (IQR 59.2, 103.3) dB. As for audiogram. there were 4 cases (5.6%) of ascending type, 24 (33.8%) of descending type, 19 (26.8%) of flat type and 24 (33.8%) of profound type. The median of the outcome hearing threshold was 75 (IQR 36.7, 99.2) dB. The patients with Gorrie type C tended to have poorer clinical outcomes than type B (p = 0.016) and there was no significant difference in the initial hearing threshold, audiogram configuration and outcome hearing threshold between other vascular types classified by the Kazawa, Chavda or Gorrie system.

Relationship between vestibular function tests and imaging classification results

No significant difference was found in the CP value of the caloric test, the abnormal rate of cVEMP or the abnormal rate of oVEMP among the various types classified by Kazawa, Chavda and Gorrie systems. Referring to previous literature reporting a higher incidence in PSCC deficits in patients with ISSNHL and its correlation with hearing outcome 4,5, the vHIT results on the affected side were divided into three groups: normal vHIT results; abnormal results in PSCC; abnormal results without PSCC abnormality. Comparing the vHIT results among the various types, there was no significant difference. The detailed results are shown in Table IV.

Relationship between hearing outcome and vestibular function tests

The clinical outcome was used as a dependent variable, and normal/abnormal results in caloric test, cVEMP, oVEMP, vHIT ASCC, vHIT HSCC, and vHIT PSCC were used as independent variables respectively to establish the ordinal logistic regression model. Patients with vHIT abnormal results in PSCC were more prone to poor clinical outcomes (Tab. V).

Discussion

No association between the neurovascular compression in CPA-IAC region and vestibular tests in patients with ISSNHL

In this study, using three anatomical classification systems, no direct evidence of neurovascular compression in the CPA-IAC region associated with the hypofunction of vestibular end organs in ISSNHL patients was found. Although several previous studies have examined the relationship between the radiological sign of neurovascular compression in CPA-IAC and the clinical profile and hearing outcomes for patients with ISSNHL, to the best of our knowledge, the present study is the first to document the relevance of this imaging sign to vestibular impairment in these patients 10,11,13. Two pathophysiological hypotheses were proposed for vascular-cranial nerve compression syndrome. Firstly, the progressive pulsatile vascular compression of the nerve can result in focal demyelination, reorganisation and axonal hyperactivity in the central glial and peripheral non-glial junction (also named as transition zone) 17,18. This process may be accelerated by arteriosclerosis and by arachnoid adhesions that cause fixation of the vessel to the nerve 19. The second hypothesis is that neurovascular compression might gradually leads to a decrease in vascular perfusion. Although the vascular compression syndromes have been considered a major cause of hemifacial spasm and trigeminal neuralgia 20, its role in audio-vestibular symptoms remains debatable. The mechanism of vestibular impairment in ISSNHL patients is also unclear. Although the comprehensive evaluation of vestibular function can locate the damaged vestibular end organs, the exact cause of these impairments cannot be determined by the results of vestibular tests alone. Some studies have reported significantly elevated levels of antibodies related to autoimmunity or serological markers of viral infection in ISSNHL patients 21,22. However, whether these potential causes contribute to the vestibular symptoms in ISSNHL remains inconclusive. The present study demonstrated that the vascular-cranial nerve compression in the CPA-IAC region may not be involved in the mechanism of vestibular impairment in ISSNHL patients.

To date, few studies have addressed the association between vestibular deficits and signs of neurovascular compression in the CPA-IAC region 23,24. Loader et al. found that in vestibular neuritis cases, compared to patients with pathological caloric test results and healthy controls, patients who presented with acute vestibular dysfunction but without abnormal caloric results had significantly increased prevalence of neurovascular conflicts 23. In the research of Di Stadio et al., vestibular hypofunction confirmed by caloric test in patients with asymmetric audio-vestibular symptoms was significantly correlated with the calibre of the vessels involved in loop and the number of contacts between loop and CVN 24. Many studies in recent years have found characteristic PSCC injury in ISSNHL patients, which is believed can be explained by the haemodynamic abnormalities of the inner ear. The blood supply of PSCC is from the posterior vestibular artery, one of the branches from AICA, however, according to the present results, the PSCC paresis in ISSNHL patients may not be due to the neurovascular compression in the CPA-IAC region. The bioimaging marker of inner ear end organ deficit in ISSNHL patients remains to be explored.

Clinical features and neurovascular compression in CPA-IAC region in ISSNHL patients

We found that Chavda type II (AICA loop inside the IAC, extending < 50%) was more common in patients with vertigo, while Chavda type I (AICA loop outside the IAC) was more common in ISSNHL patients who did not complain of vertigo. Accompanying symptom of tinnitus, initial hearing threshold, and hearing threshold after treatment were not associated with the variation of neurovascular relationships. In our previous study with different participants, the same three systems were used to classify the neurovascular anatomical relationship in the CPA-IAC region for ISSNHL patients. No association between vertigo symptoms and different types was found. However, in terms of patients with tinnitus, the Kazawa type IIA is significantly more common than type IB 10. Kim et al. applied the Gorrie and Chavda classification systems in ISSNHL patients and found that the AICA types did not affect the incidence of vertigo or tinnitus 11. The variations among these findings may be attributed to the differences of the subjects enrolled. On the other hand, it also suggests that these commonly used imaging classification systems are not stable methods for differentiating ISSNHL symptoms.

According to a recent systematic review, AICA loops in the CPA-IAC region were very common in patients with audio-vestibular symptoms. In nearly 70% of these patients, no correlation was found between vascular loops and symptoms 11. Therefore, it was proposed that the AICA loops could be regarded as a normal anatomical variation 9,25. However, most of the studies in the systematic review enrolled patients with asymmetric audio-vestibular symptoms, rather than patients with confirmed diagnosis of ISSNHL. The lack of consistent inclusion criteria prevents us from simply excluding neurovascular compression from the possible pathological mechanisms of symptoms in ISSNHL patients. Whether the vertigo or tinnitus in ISSNHL patients are related to neurovascular compression in the CPA-IAC region needs further study with larger sample in the future.

Hearing prognostic factors in ISSNHL: vestibular impairment versus neurovascular compression

In this study, ISSNHL patients with pathological vHIT results from PSCC were more prone to poor hearing recovery. In previous studies of ISSNHL patients, multivariate analyses of vHIT and VEMP results in ISSNHL patients showed that PSCC impairment was significantly correlated with incomplete hearing recovery 4,5. Seo et al. reported that among the 5 vestibular end organs, only damage of PSCC was associated with poor prognosis for hearing recovery 4. Byun et al. found that decreased vHIT gain in PSCC was a specific prognostic factor for incomplete hearing recovery in ISSNHL patients 5. The susceptibility to ischaemia of the cochlea may provide an explanation for these findings. The CCA branched from the labyrinthine artery supplies the PSCC, the inferior portion of saccule, and the cochlea. PSCC is solely supplied by the CCA, whereas the saccule receives dual blood supply from AVA. Therefore, the ischaemia of CCA could result in isolated hypofunction of PSCC in ISSNHL patients, accompanied with severe hearing loss. In conclusion, from previous findings and present results, the dysfunction of PSCC is of good consistency with poor hearing outcomes in patients with ISSNHL.

This study found that ISSNHL patients with Gorrie type C (the AICA loop running between the VII cranial nerve and CVN) were more likely to have poor hearing outcomes than those with type B (the AICA loop was adjacent to the nerves), while outcomes did not differ between types based on the Kazawa or Chavda classification systems. This finding was consistent with our previous study 10. In a study using the Kazawa classification system, Ezerarslan et al. found that ISSNHL patients with Kazawa type IIB (AICA/PICA loop entering the IAC) had a worse response to standard treatment 13. Furthermore, Kim et al. found that there were no significant differences in the hearing outcomes among the subtypes classified by the Chavda or Gorrie systems 11. The variability of these results suggests that the current imaging classification systems are not stable in predicting hearing outcomes in ISSNHL patients.

The hearing prognosis of ISSNHL patients is affected by various factors including age, degree of hearing loss, presence of vertigo, audiometric configuration, duration from onset to treatment, and underlying diseases such as hypertension and diabetes 1,26. For instance, it has been found that low monocyte counts were associated with good prognosis in ISSNHL patients 27. In view of the fact that a considerable proportion (45.5-62.1%) of ISSNHL patients presenting pathological vestibular test results did not complain of dizziness or vertigo subjectively 4-6, when predicting the prognosis of ISSNHL patients, an overall consideration including the results of blood tests, vestibular tests and other related factors may be necessary due to the complex aetiology of ISSNHL. The present and previous studies found that the impaired PSCC was associated with poor hearing outcomes in ISSNHL patients. However, the results of imaging classification systems were not consistent with hearing outcomes. It suggests that the neurovascular compression in CPA-IAC region may not be a stable predictor and current imaging classification systems needs further optimisation.

This study is the first to apply three classification methods to explore the relationship between neurovascular compression signs and vestibular function in patients with ISSNHL. Due to the objective limitations in present study, there is still room for further refinement. As a retrospective study, this research is limited by variations in the timing of patients'; initial visits and follow-ups, which may introduce bias. Moreover, the sample size was limited by the availability of clinical data, and a control group could not be included due to incomplete historical records. Future studies with larger prospective cohorts and well-defined control groups are warranted to further support our findings and provide a more comprehensive understanding of the relationship between neurovascular compression, hearing outcomes and vestibular dysfunction. Secondly, the neurovascular relationship of CVN and AICA in CPA-IAC region were evaluated by three imaging classification systems commonly used before. There is no generally recognised imaging classification system at present. Future studies need to deepen the research on the classification technology in order to evaluate the neurovascular relationships in the CPA-IAC region more reliably and generally accepted.

Conclusions

No association between vestibular testing results and radiological neurovascular compression signs in the CPA-IAC region was found in patients with ISSNHL. The hearing outcomes of ISSNHL patients was correlated with vestibular compromise rather than neurovascular compression signs.

Conflict of interest statement

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Funding

This work was supported by the National Key Research and Development Program of China (Nos. 2023YFC2508000 and 2023YFC2508001) the National Natural Science Foundation of China (NSFC NO. 81670930), the Natural Science Foundation of Hubei Province, China (No. 2021CFB547), and the Open Program of Hubei Province Key Laboratory of Molecular Imaging (No. 2023fzyx003). Ping Lei analyzed the data and drafted the manuscript; Cen chen helped the data collection. Bo Liu and Hongjun Xiao reviewed and revised the manuscript for important intellectual content.

Author contributions

All authors participated in the study’s conception and design. YL, PL: analyzed the data and drafted the manuscript; CC, KX, RZ: helped the data collection; YL, BL, HX: reviewed and revised the manuscript for important intellectual content.

Ethical consideration

This study was approved by the Ethics Committee of Union Hospital affiliated to Tongji Medical College, Huazhong University of Science and Technology, Wuhan, China [approval number (2022) No. 0082-01].

The research was conducted ethically, with all study procedures being performed in accordance with the requirements of the World Medical Association’s Declaration of Helsinki.

Written informed consent was obtained from each participant for study participation and data publication.

History

Received: December 30, 2024

Accepted: July 10, 2025

Figures and tables

Figure 1. Kazawa classification of anterior inferior cerebellopontine artery (AICA) loop. (1a-h) Type IA in which nonloop AICA (arrow) in the cistern; (2a-h) Type IB in which nonloop AICA (arrow) into the internal auditory canal (IAC); (3a-p) Type IIA (right side) in which loop type AICA (arrow) in the cerebellopontine angle (CPA) cistern and type IIB (left side) in which loop type AICA (arrow) enters the IAC.

Figure 2. Chavda classification of AICA loop. (a) AICA loop (arrow) observed in CPA outside the IAC which is type I; (b) Type II in which AICA loop (arrow) is occupying no more than 50% of IAC; (c) Type III in which AICA loop (arrow) leaches more than 50% of total length of IAC.

Figure 3. Gorrie classification of AICA loop. (a,e) AICA loop (A) running separate from cranial nerve (B,C) which is type A; (b,f) Type B in which the AICA loop (A) is running adjacent to the cranial nerve (B,C); (c,g) Type C in which the AICA loop (A) runs between the 7th (C) and 8th (B) cranial nerve; (d,h) Type D in which the AICA loop (A) displacing the nerve resulting in bowing of the nerve (B).

Figure 4. AICA types of affected and non-affected side in unilateral ISSNHL patients classified by Kazawa (A), Chavda (B), and Gorrie systems (C).

| Classification grade | Subtype | Detailed description |

|---|---|---|

| Kazawa system | IA | Non-loop AICA/PICA in the CPA cistern |

| IB | Non-loop AICA/PICA entering the IAC | |

| IIA | Loop-type AICA/PICA in the CPA cistern | |

| IIB | Loop-type AICA/PICA entering the IAC | |

| Chavda system | I | AICA loops lying within the CPA but not entering the IAC |

| II | AICA loops entering the IAC but not extending more than 50% of the length of the IAC | |

| III | AICA loops extending more than 50% of the length of the IAC | |

| Gorrie system | A | No contact between the vascular loop and the CVN |

| B | Vascular loop lying directly adjacent to the CVN | |

| C | Vascular loop running between the VII nerve and CVN | |

| D | Vascular loop displacing the CVN resulting the bowing of the nerve | |

| AICA: anterior inferior cerebellopontine artery; PICA: posterior inferior cerebellopontine artery; CPA: cerebellopontine angle; IAC: internal acoustic canal; CVN: cochleovestibular nerve. | ||

| Gender (male/female) | Age (yrs), mean +/- SD | Course duration (days), mean (IQR) | Affected side (left/right) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Kazawa system | IA (n = 10) | 7/3 | 44.6 ± 13.9 | 9 (4.3, 15) | 7/3 |

| IB (n = 17) | 8/9 | 41.8 ± 13 | 6 (1, 11) | 9/8 | |

| IIA (n = 30) | 13/17 | 44.5 ± 17.5 | 7.5 (3, 15.3) | 18/12 | |

| IIB (n = 14) | 6/8 | 45.6 ± 11.8 | 6 (3, 20) | 10/4 | |

| Test statistics | χ2 = 2.399 | - | - | χ2 = 1.459 | |

| p value | 0.509 | 0.661 | 0.275 | 0.693 | |

| Chavda system | I (n = 40) | 20/20 | 41.7 ± 12.8 | 7.5 (3, 15) | 25/15 |

| II (n = 29) | 14/15 | 43.1 ± 12.7 | 6 (2.5, 13.5) | 18/11 | |

| III (n = 2) | 0/2 | 48.5 ± 6.4 | 5.5 (4, -) | 1/1 | |

| Test statistics | - | F = 0.336 | - | - | |

| p value | 0.607 | 0.716 | 0.331 | 1 | |

| Gorrie system | A (n = 6) | 1/5 | 39.3 ± 15.1 | 8.5 (2.8, 13.5) | 4/2 |

| B (n = 26) | 16/10 | 40.5 ± 13.5 | 7 (2, 15) | 14/12 | |

| C (n = 21) | 9/12 | 44 ± 11.2 | 8 (3, 20) | 14/7 | |

| D (n = 18) | 8/10 | 44.7 ± 12.3 | 5.5 (3, 13.3) | 12/6 | |

| Test statistics | χ2 = 4.834 | F = 0.601 | - | χ2 = 1.141 | |

| p value | 0.208 | 0.616 | 0.880 | 0.821 | |

| ISSNHL: idiopathic sudden sensorineural hearing loss; AICA: anterior inferior cerebellar artery; SD: standard deviation; IQR: interquartile ranges (25th and 75th percentiles). | |||||

| Tinnitus (%) | Vertigo (%) | Initial hearing threshold (dB), mean (IQR) | Audiogram (up/down/flat/total) | Outcome hearing threshold (dB), mean (IQR) | Clinical outcome (CR/GR/PR/NR) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Kazawa system | IA (n = 10) | 9 (90%) | 5 (50%) | 83 (54, 104) | 1/3/3/3 | 87 (34, 101) | 2/1/0/7 |

| IB (n = 17) | 13 (76.5%) | 12 (70.6%) | 95 (69, 111) | 1/4/4/8 | 84 (49, 104) | 2/2/4/9 | |

| IIA (n = 30) | 29 (96.7%) | 14 (46.7%) | 83 (54, 104) | 1/10/8/11 | 70 (29, 98) | 7/3/3/17 | |

| IIB (n = 14) | 13 (92.9%) | 10 (71.4%) | 89 (66, 101) | 1/7/4/2 | 70 (42, 102) | 1/2/3/8 | |

| Test statistics | χ2 = 4.616 | χ2 = 4.049 | F = 0.235 | χ2 = 6.009 | - | - | |

| p value | 0.148 | 0.277 | 0.872 | 0.753 | 0.770 | 0.927 | |

| Chavda system | I (n = 40) | 38 (95%) | 19 (47.5%) | 83 (56, 104) | 2/13/11/14 | 76 (31, 98) | 9/4/3/24 |

| II (n = 29) | 25 (86.2%) | 22 (75.9%) | 89 (71, 105) | 2/10/7/10 | 78 (47, 103) | 2/4/6/17 | |

| III (n = 2) | 1 (50%) | 0 | 72 (48, -) | 0/1/1/0 | 43 (18, -) | 1/0/1/0 | |

| Test statistics | χ2 = 4.840 | χ2 = 7.955 | - | χ2 = 2.660 | - | - | |

| P value | 0.079 | 0.012 | 0.724 | 0.974 | 0.268 | 0.263 | |

| Gorrie system | A (n = 6) | 6 (100%) | 2 (33.3%) | 77 (55, 102) | 1/2/1/2 | 62 (23, 101) | 2/0/1/3 |

| B (n = 26) | 24 (92.3%) | 13 (50%) | 80 (57, 97) | 0/10/9/7 | 66 (34, 98) | 5/6/5/10 | |

| C (n = 21) | 19 (90.5%) | 16 (76.2%) | 96 (78, 113) | 0/5/5/11 | 90 (65, 109) | 1/0/2/18 | |

| D (n = 18) | 15 (83.3%) | 10 (55.6%) | 83 (50, 103) | 3/7/4/4 | 62 (28, 97) | 4/2/2/10 | |

| Test statistics | χ2 = 1.372 | χ2 = 5.251 | - | χ2 = 11.516 | - | - | |

| p value | 0.707 | 0.174 | 0.346 | 0.185 | 0.123 | 0.016 | |

| CR: complete recovery; GR: good recovery; PR: poor recovery; NR: non-responders; IQR: interquartile range (25th and 75th percentiles). | |||||||

| CP value (%), mean (IQR) | cVEMP (N/A) | oVEMP (N/A) | vHIT (N/abnormal PSCC/abnormal without PSCC abnormality) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Kazawa system | IA | 15.5 (3.5, 43) | 6/3 | 5/3 | 7/3/0 |

| IB | 27 (10, 40) | 9/4 | 10/4 | 10/7/0 | |

| IIA | 29.5 (10, 46.8) | 16/11 | 9/6 | 20/9/1 | |

| IIB | 17 (7, 58) | 3/5 | 2/6 | 11/3/0 | |

| Test statistics | - | χ2 = 2.258 | χ2 = 4.495 | χ2 = 3.575 | |

| p value | 0.744 | 0.540 | 0.225 | 0.871 | |

| Chavda system | I | 25.5 (8.5, 44.75) | 22/14 | 14/9 | 27/12/1 |

| II | 19 (9.5, 41) | 12/9 | 12/8 | 19/10/0 | |

| III | 4 | - | 0/2 | 2/0/0 | |

| Test statistics | - | χ2 = 0.087 | χ2 = 2.458 | χ2 = 3.263 | |

| p value | 0.409 | 0.768 | 0.312 | 0.947 | |

| Gorrie system | A | 27 (9.5, 42.5) | 4/2 | 3/1 | 6/0/0 |

| B | 20 (8, 48.3) | 13/7 | 9/7 | 19/7/0 | |

| C | 19 (8, 34.5) | 10/8 | 10/5 | 13/8/0 | |

| D | 30 (9.5, 51) | 7/6 | 4/6 | 10/7/1 | |

| Test statistics | - | χ2 = 0.775 | χ2 = 2.229 | χ2 = 7.347 | |

| p value | 0.845 | 0.922 | 0.593 | 0.257 | |

| CP: canal paresis; cVEMP: cervical vestibular evoked myogenic potential; oVEMP: ocular vestibular evoked myogenic potential; vHIT: video head impulse test; PSCC: posterior semicircular canal; N: normal; A: abnormal; IQR: interquartile range (25th and 75th percentiles). | |||||

| CR | GR | PR | NR | Test statistics | p value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Caloric test (N/A) | 6/6 | 7/1 | 4/5 | 20/21 | β = 0.372 | 0.430 |

| cVEMP (N/A) | 9/1 | 4/1 | 1/3 | 19/18 | β = 1.124 | 0.068 |

| oVEMP (N/A) | 7/3 | 3/2 | 2/3 | 14/11 | β = 0.334 | 0.568 |

| vHIT ASCC (N/A) | 12/0 | 8/0 | 9/1 | 36/5 | β = 1.517 | 0.190 |

| vHIT HSCC (N/A) | 12/0 | 7/1 | 8/2 | 30/11 | β = 1.320 | 0.064 |

| vHIT PSCC (N/A) | 12/0 | 7/1 | 6/4 | 24/17 | β = 1.475 | 0.012 |

| ASCC: anterior semicircular canal; HSCC: horizontal semicircular canal; PSCC: posterior semicircular canal; CR: complete recovery; GR: good recovery; PR: poor recovery; NR: non-responders. | ||||||

| Scanning Parameters (3.0T) | T1 weighted imaging | T2 weighted imaging | 3D-SPACE |

|---|---|---|---|

| Plane | Sagittal and axial | Axial | Axial |

| TR (ms) | 300 | 9000 | 1000 |

| TE (ms) | 2 | 90 | 135 |

| Fat saturation | / | TIR | / |

| Slice thickness (mm) | 5 | 5 | 0.5 |

| Slices (no.) | 15 | 17 | 56 |

| FOV (mm2) | 250×250 | 220×200 | 200×200 |

| Matrix | 320×320 | 640×640 | 384×384 |

| Averages | 1 | 1 | 2 |

| Bandwidth (Hz/Px) | 330 | 287 | 289 |

| MR: magnetic resonance; 3D-SPACE: three-dimensional sampling perfection with application optimised contrasts using different flip angle evolutions; TR: repetition time; TE: echo time; FOV: field of view. | |||

References

- Chandrasekhar S, Tsai Do B, Schwartz S. Clinical practice guideline: sudden hearing loss (update). Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2019;161:S1-S45. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/0194599819859885

- Chau J, Lin J, Atashband S. Systematic review of the evidence for the etiology of adult sudden sensorineural hearing loss. Laryngoscope. 2010;120:1011-1021. doi:https://doi.org/10.1002/lary.20873

- Nosrati-Zarenoe R, Arlinger S, Hultcrantz E. Idiopathic sudden sensorineural hearing loss: results drawn from the Swedish national database. Acta Otolaryngol. 2007;127:1168-1175. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/00016480701242477

- Seo H, Chung J, Byun H. Vestibular mapping assessment in idiopathic sudden sensorineural hearing loss. Ear Hear. 2022;43:242-249. doi:https://doi.org/10.1097/AUD.0000000000001129

- Byun H, Chung J, Lee S. Clinical implications of posterior semicircular canal function in idiopathic sudden sensorineural hearing loss. Sci Rep. 2020;10. doi:https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-020-65294-5

- Guan R, Zhao Z, Guo X. The semicircular canal function tests contribute to identifying unilateral idiopathic sudden sensorineural hearing loss with vertigo. Am J Otolaryngol. 2020;41. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.amjoto.2020.102461

- Yu H, Li H. Association of vertigo with hearing outcomes in patients with sudden sensorineural hearing loss: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2018;144:677-683. doi:https://doi.org/10.1001/jamaoto.2018.0648

- Jannetta P. Neurovascular cross-compression in patients with hyperactive dysfunction symptoms of the eighth cranial nerve. Surg Forum. 1975;26:467-469.

- Papadopoulou A, Bakogiannis N, Sofokleous V. The impact of vascular loops in the cerebellopontine angle on audio-vestibular symptoms: a systematic review. Audiol Neurootol. 2022;27:200-207. doi:https://doi.org/10.1159/000521792

- Leng Y, Lei P, Liu Y. Vascular loops in cerebellopontine angle in patients with unilateral idiopathic sudden sensorineural hearing loss: evaluations by three radiological grading systems. Laryngoscope Investig Otolaryngol. 2022;7:1532-1540. doi:https://doi.org/10.1002/lio2.876

- Kim S, Ju Y, Choi J. Anatomical location of AICA loop in CPA as a prognostic factor for ISSNHL. Peer J. 2019;7. doi:https://doi.org/10.7717/peerj.6582

- Ungar O, Brenner-Ullman A, Cavel O. The association between auditory nerve neurovascular conflict and sudden unilateral sensorineural hearing loss. Laryngoscope Investig Otolaryngol. 2018;3:384-387. doi:https://doi.org/10.1002/lio2.209

- Ezerarslan H, Sanhal E, Kurukahvecioğlu S. Presence of vascular loops entering internal acoustic channel may increase risk of sudden sensorineural hearing loss and reduce recovery of these patients. Laryngoscope. 2017;127:210-215. doi:https://doi.org/10.1002/lary.26054

- McDermott A, Dutt S, Irving R. Anterior inferior cerebellar artery syndrome: fact or fiction. Clin Otolaryngol Allied Sci. 2003;28:75-80. doi:https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1365-2273.2003.00662.x

- Gorrie A, Warren F, de la Garza A. Is there a correlation between vascular loops in the cerebellopontine angle and unexplained unilateral hearing loss?. Otol Neurootol. 2010;31:48-52. doi:https://doi.org/10.1097/MAO.0b013e3181c0e63a

- Kazawa N, Togashi K, Ito J. The anatomical classification of AICA/PICA branching and configurations in the cerebellopontine angle area on 3D-drive thin slice T2WI MRI. Clin Imaging. 2013;37:865-870. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.clinimag.2011.11.021

- Haller S, Etienne L, Kövari E. Imaging of neurovascular compression syndromes: trigeminal neuralgia, hemifacial spasm, vestibular paroxysmia, and glossopharyngeal neuralgia. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 2016;37:1384-1392. doi:https://doi.org/10.3174/ajnr.A4683

- Nowé V, De Ridder D, Van De Heyning P. Does the location of a vascular loop in the cerebellopontine angle explain pulsatile and non-pulsatile tinnitus?. Eur Radiol. 2004;14:2282-2289. doi:https://doi.org/10.1007/s00330-004-2450-x

- Van Der Steenstraten F, De Ru J, Witkamp T. Is microvascular compression of the vestibulocochlear nerve a cause of unilateral hearing loss?. Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol. 2007;116:248-252. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/000348940711600404

- Jannetta P. Trigeminal neuralgia and hemifacial spasm – Etiology and definitive treatment. Trans Am Neurol Assoc. 1975;100:89-91.

- Fukuda S, Chida E, Kuroda T. An anti-mumps IgM antibody level in the serum of idiopathic sudden sensorineural hearing loss. Auris Nasus Larynx. 2001;28:S3-S5. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/s0385-8146(01)00081-5

- Toubi E, Ben-David J, Kessel A. Immune-mediated disorders associated with idiopathic sudden sensorineural hearing loss. Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol. 2004;113:445-449. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/000348940411300605

- Loader B, Linauer I, Korkesch S. A connection between neurovascular conflicts within the cerebellopontine angle and vestibular neuritis, a case controlled cohort study. Acta Otorhinolaryngol Ital. 2016;36:421-427. doi:https://doi.org/10.14639/0392-100X-766

- Di Stadio A, Dipietro L, Ralli M. Loop characteristics and audio-vestibular symptoms or hemifacial spasm: is there a correlation? A multiplanar MRI study. Eur Radiol. 2020;30:99-109. doi:https://doi.org/10.1007/s00330-019-06309-2

- Walijee H, Vaughan C, Munir N. Microvascular compression of the vestibulocochlear nerve. Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol. 2021;278:3625-3631. doi:https://doi.org/10.1007/s00405-020-06586-4

- Kim J, Han J, Sunwoo W. Sudden sensorineural hearing loss in children and adolescents: clinical characteristics and age-related prognosis. Auris Nasus Larynx. 2018;45:447-455. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.anl.2017.08.010

- Doo J, Kim D, Kim Y. Biomarkers suggesting favorable prognostic outcomes in sudden sensorineural hearing loss. Int J Mol Sci. 2020;21. doi:https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms21197248

Downloads

License

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

Copyright

Copyright (c) 2025 Società Italiana di Otorinolaringoiatria e chirurgia cervico facciale

How to Cite

- Abstract viewed - 798 times

- PDF downloaded - 185 times