Otology

Vol. 45: Issue 6 - December 2025

Metastastic potential of middle ear neuroendocrine tumours

Abstract

Objective. Middle ear neuroendocrine tumours (MeNETs) are rare neoplasms of the temporal bone. Although the clinical behaviour of MeNETs is often indolent, a subset demonstrates aggressive progression with locally invasive and metastatic disease. This study aims to describe the clinical presentation, progression, and outcomes of middle ear neuroendocrine tumours in 3 patients with particularly unfavourable clinical courses.

Methods. We retrospectively reviewed 3 patients diagnosed with MeNETs who developed locally invasive tumours and distant metastases. Data on clinical features, diagnostic findings, management and long-term outcomes were reviewed.

Results. All 3 patients described in this report developed distant metastases over a period of 6 to 16 years after initial diagnosis. Two of the 3 patients eventually died from their disease. No distinct clinical features could be identified that were predictive of an unfavourable course.

Conclusions. A subset of MeNETs can follow an aggressive clinical course with metastatic spread and, in some cases, tumour-related death, even after an initial period of seemingly benign behaviour. Comprehensive diagnostic work-up and prolonged follow-up are essential for patients with MeNETs.

Introduction

Middle ear neuroendocrine tumours (MeNETs) comprise a rare and diverse group of tumours of the temporal bone. In a recent review of the literature, only 198 reported cases were identified 1. Although most MeNETs are characterised by benign biological behaviour and an indolent growth pattern, some studies have reported locally invasive and metastatic spread, suggesting that these tumours should be considered a low-grade malignancy 2-13. This malignant behaviour is exceedingly rare, only 13 of the 198 cases reported worldwide showed metastatic disease, both regionally and at distance.

Currently, reliable prediction of the aggressiveness of MeNETs remains elusive due to lack of prognostic factors 1. Here, we will discuss 3 patients with MeNETs who developed distant metastases. All three cases are characterised by a prolonged course of the disease, the occurrence of metastases at distance, and resistance to therapy.

Case reports

Case 1

A 38-year-old woman was seen elsewhere with a left-sided facial nerve paralysis and presumed otitis media with effusion. The facial nerve function recovered after steroid treatment, but the otitis media persisted despite of tympanostomy tube placement and local antibiotic treatment. Computed tomography (CT) demonstrated an opacification of the middle ear and mastoid air cells without evidence of bone invasion. An exploratory mastoidectomy revealed granulation tissue in the mastoid, antrum and epitympanum. The histopathology report concluded an adenocarcinoma. The patient was referred to a tertiary referral centre for definitive management. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) demonstrated an infiltrative tumour, affecting the tympanomastoid segment of the facial nerve and the midcranial fossa tegmen, without intracranial extension (Fig. 1). Nuclear imaging was negative for metastasis or concurrent tumours.

An en-bloc tumour removal was performed by means of a subtotal temporal bone resection including resection of the mandibular condyle and facial nerve trunk in the stylomastoid foramen, superficial parotidectomy, and selective neck dissection 14. The facial nerve was reconstructed with a hypoglossal-facial nerve interpositional-jump graft and the residual cavity was obliterated with abdominal fat and temporalis muscle flap. Histopathology showed an infiltrative tumour with positive resection margins at the infratemporal bone and midcranial fossa dura. Postoperative locoregional radiation therapy (66 Gy total dose) was given. Six months after radiotherapy, a follow-up 18 fluorodeoxyglucose PET/CT scan was performed which showed no pathological uptake.

After 6 years of follow-up, a cervical lymph node and hepatic and bone metastasis were identified on MR and CT, which were avid on 68 Ga-DOTATATE-PET/CT. Liver biopsy and cervical lymph node cytology confirmed the diagnosis of metastasis and histopathology showed neuroendocrine characteristics on immunohistochemistry. Retrospective immunohistochemical analysis of the primary middle ear tumour showed corresponding neuroendocrine characteristics, expressing synaptophysin and chromogranin A. The final diagnosis was revised from primary adenocarcinoma to metastasised neuroendocrine tumour of the mastoid and middle ear. No mitoses were seen and the Ki-67 labelling index was less than 2% in both the primary tumour and liver metastasis.

Longacting release octreotide treatment (OCT-LAR) ensued and two large liver metastases were embolised. After one year of stable disease, progressive liver metastases and rising chromogranin-B levels indicated OCT-LAR refractory disease. Peptide radionuclide receptor therapy (PRRT) was given and resulted in a partial response. Fifteen months after the start of PRTT, cross-sectional imaging revealed progressive disease in the liver and peritonitis carcinomatosis. Three courses of chemotherapy with carboplatin and etoposide were administered, but the patient developed progressive disease and finally died of the disease 11 years after the initial diagnosis.

Case 2

A 53-year-old male presented with right-sided otalgia. He had been surgically treated 15 years earlier for an ipsilateral cholesteatoma. Physical examination revealed a tumour in the operated mastoid cavity, which was removed via a mastoidectomy. Histopathology showed an adenomatous neuroendocrine tumour. The patient was referred to a tertiary referral centre where the histological diagnosis was confirmed. Examination of the right ear showed no macroscopic evidence of tumour residue. Because the patient had no complaints and the tumour was considered benign, active surveillance was opted for.

Three years after initial presentation, follow-up CT and MR imaging revealed an enhancing middle ear mass in the operated mastoid cavity and external ear canal. The tumour was macroscopically removed with a modified canal wall down mastoidectomy. Histopathology confirmed recurrence of the neuroendocrine tumour.

In the following year, the patient developed a facial nerve palsy. CT and MR imaging showed a mass suspect for recurrence in the right stylomastoid foramen (Fig. 1). Repeated fine needle aspiration biopsies of the palpable mass showed necrotising inflammation. The facial nerve function recovered after cortisone treatment. It was decided to continue monitoring with regular CT imaging.

Three years later, lymph node metastases in the ipsilateral parotid gland and neck were noted. A subtotal petrosectomy, ipsilateral parotidectomy and modified radical neck dissection were performed. The ear canal and middle ear were filled with tumour, accompanied by cholesteatoma adherent to the horizontal portion of the facial nerve. Macrosopical total resection was achieved. No infiltration of the dura was observed, although MRI suggested growth in the temporal lobe (Fig. 1). Histopathology of specimens taken from the mastoid, cervical lymph nodes and parotid revealed a neuroendocrine tumour, the mastoidal biopsies showed infiltration of the surrounding bone. The mitotic activity was elevated in comparison with the primary tumour. Postoperative locoregional radiotherapy of 60 Gy was administered. The following 2 years MRI showed an unchanged mass in the middle fossa, suggestive for stable residual disease. At that time a palpable mass developed in the abdomen. CT imaging of the abdomen demonstrated multiple liver metastases and an enlarged para-aortal lymph node, which were histologically confirmed metastases of the neuroendocrine tumour. These metastases were considered inoperable. An I-123 meta-iodobenzylguanidine (MIBG) scan was performed which showed sufficient accumulation for I-131-MIBG therapy. I-131-MIBG treatment was started, but the patient developed progressive liver and bone metastases. Palliative care was given and the patient died of the disease 9 years after the initial diagnosis.

Case 3

A 33-year-old male presented with complaints of left-sided conductive hearing loss, tinnitus and otalgia. Physical examination revealed a neoplastic lesion in the middle ear, extending into the external ear canal. Histopathology showed an adenomatous neuroendocrine tumour. The tumour was removed with combined tympanoplasty and posterior tympanotomy.

Nine years later, otoscopy revealed a recurrent tumour in the left ear. CT imaging showed a middle ear mass surrounding the stapes, which extended into the external ear canal. The tumour was removed with a combined tympanoplasty. Histopathologic examination confirmed recurrence of a neuroendocrine tumour, with Ki-67 expression between 5% and 10%.

One year after the second surgery, a third look tympanoplasty was performed, which showed no recurrent tumour. After this third look procedure, a fourth middle ear and mastoid inspection was performed because the patient suffered from progressive conductive hearing loss and CT imaging showed a middle ear mass encasing the stapes. During this middle ear inspection, a recurrence in the middle ear was identified and removed. After this procedure, four additional procedures followed during a 3-year time interval, each revealing a recurrence. Histopathological examination confirmed the recurrence of the neuroendocrine tumour, with Ki-67 expression similar to the first recurrence.

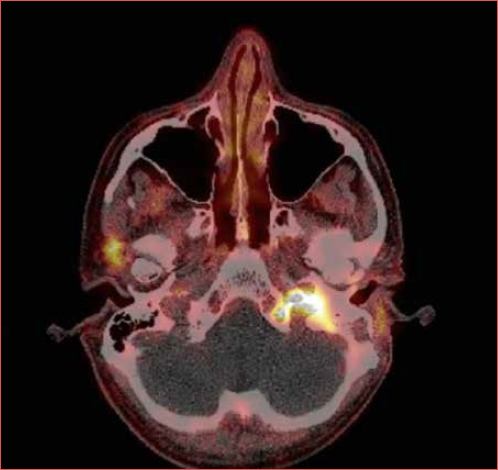

Six months after the last ear surgery, the patient presented with ipsilesional glossopharyngeal and hypoglossal nerve palsy. MR imaging and 68Ga-DOTATATE-PET/CT revealed an avid mass in the jugular foramen, extending into the hypoglossal, carotid and vertebral canal of C1 (Cover figure). Because the tumour was deemed unresectable, the patient was treated with local radiotherapy (68 Gy total dose) and somatostatin analogue (SSA) therapy every 4 weeks. Six months later, 68 Ga-DOTATATE-PET scanning showed stable local disease and no metastases.

However, one year later, multiple liver lesions were identified on 68 Ga-DOTATATE-PET scan. Liver biopsies confirmed the presence of neuroendocrine metastases with a Ki-67 index of 19%. It was decided to discontinue SSA therapy and initiate palliative PRRT. The patient is currently still under treatment.

Histopathology

In all three patients, the specimens of the tumour in the temporal bone, the lymph nodes and liver metastasis showed the same basic histology. In patient 1, microscopic examination revealed a tumour composed of atypical epithelial cells with a cribriform growth pattern (Fig. 2). The cells showed pleiomorphism, sporadic nucleoli and sparse eosinophilic cytoplasm. The tumour invaded the petrosal bone including the cochlea. Immunohistochemistry showed positive staining for synaptophysin and chromogranin A. Mitotic figures were rare and the Ki-67 labelling index was < 2%.

In patient 2, tumour cells were arranged in nests, trabeculae and acini and showed a proliferation of atypic epithelial cells with eosinophilic cytoplasm and hyperchromatic nuclei with granular chromatin. The cells contained round nuclei with occasionally one or more nucleoli. Immunohistochemical stains were positive for keratin AE1/AE3, CD 56, vimentin, chromogranin A, and synaptophysin and negative for S-100 protein. The original pathology report of the primary tumour described sporadic mitotic figures, but no specific mitotic count was provided. As the case dates back over two decades, re-analysis of the histological slides was no longer possible. The morphology of both the recurrence and the cervical metastases was well-differentiated. However, in contrast with the primary tumour, the recurrence and metastases exhibited a significant change in mitotic activity with a mitotic count of 2 per mm2. Unfortunately, Ki-67 immunohistochemistry was not performed. Tissue from the previously presumed cholesteatoma removed prior could not be retrieved.

In patient 3, microscopic examination revealed a tumour composed of epithelial cells with eosinophilic cytoplasm and hyperchromatic nuclei. Immunohistochemistry showed positive staining for CAM5.2, synaptophysin and chromogranin A. Mitoses were not seen and the Ki-67 index was between 5% and 10%.

Discussion

The three cases described in this report illustrate that low-grade, well-differentiated neuroendocrine tumours of the middle ear have the potential to develop into aggressively infiltrative and metastatic tumours. This malignant transformation is rarely reported, but may not be a rare occurrence in MeNETs. In addition to the three cases reported in the current manuscript, 13 cases were identified in a recent review comprising 198 MeNET cases in total 5,7-9,12,13. All three patients reported in this case series had a protracted course of the disease during which they developed metastases, and two patients eventually died of the disease.

In retrospect, we could not identify distinct clinical features at initial presentation that could be seen as predictive for an unfavourable course of the disease. In addition, there were no histopathological features or markers of the primary tumour that differentiated these 3 patients from other MeNET cases. Two of three patients had local recurrent disease before the metastasis occurred, although in patient 1 the metastasis was not preceded by local recurrence. Conversely, the review mentioned above also described patients with local recurrence who did not develop metastatic disease 1. Local recurrence therefore does not seem to be a predictor for MeNET metastasis per se.

The International Agency for Research on Cancer – World Health Organization (IARC-WHO) proposed a uniform classification system for neuroendocrine neoplasms, using the term neuroendocrine tumour (NET) for well-differentiated neoplasm and neuroendocrine carcinoma (NEC) for poorly differentiated neoplasm 15. Given the low-grade nature of the cytologic features and the lack of both necrosis and significant mitotic activity, most MeNETs have been diagnosed as low-grade, well-differentiated NETs. However, morphology alone cannot predict tumour behaviour. Proliferative rate, as assessed by the Ki-67 index, has become a useful tool in identifying the aggressive subset of gastrointestinal and lung NETs 16,17. In our first patient, the Ki-67 index in both the primary tumour and metastases was less than 2%. In the literature, the Ki-67 values reported varied widely in metastastic MeNET, ranging from 2% to 20% 1,5,9,12. This variety in proliferation rate indicates that Ki-67 index is not a reliable predictor of aggressive behaviour in MeNETs.

In the past, neuroendocrine immunohistochemistry was not performed on all adenomatous tumours of the middle ear and the tumour has been mistaken for other middle ear lesions such as adenocarcinomas, paragangliomas or ceruminomas, as was the case in patient 1. Conforming the expression of neuroendocrine markers in adenomatous tumours of the middle ear is essential to distinguish MeNET from other middle ear tumours. Traditional neuroendocrine markers include synaptophysin and chromogranin A, with the former generally considered more sensitive and the latter more specific. Recently, it has been described that NETs from the middle ear are comparable to hindgut NETs and express L cell markers, such as SATB2 18.

Surgical resection is the treatment of choice for MeNETs 1.If surgery is not possible due to the extent of disease, systemic therapy to suppress tumour growth and spread could be considered in NETs 19. Systemic therapy may not provide a cure but can induce stabilisation in inoperable or metastatic NETs, although the course of disease of patient 1 illustrates that the duration of the response can be limited. Evidence for systemic treatment efficacy is primarily based on gastroentero-pancreatic NETs. Medical treatments include SSA, PRRT, targeted drugs such as everolimus and sunitinib and cytotoxic chemotherapy. SSA therapy can be considered as first-line systemic therapy for well-differentiated, metastatic or inoperable symptomatic well-differentiated NETs with avid disease on 68 Ga-DOTATATE PET/CT 19,20. After progression on SSAs, PRRT is recommended as systematic therapy for patients with somatostatin receptor (SSTR)-positive tumors. PRRT with a SSA allows targeted delivery of radionuclides to tumor cells expressing high levels of SSTR. Chemotherapy, evorilimus or sunitinib may be offered to SSTR-negative patients and have demonstrated clinically meaningful antitumour activity in patients with advanced (metastatic or unresectable) disease.

The role of radiotherapy in NETs is debatable: whereas NETs were formerly believed to be radioresistant, recent publications have suggested that radiotherapy may play a role in the management of unresectable or metastatic lesions 21. Although there are several therapeutic options for NETs, determining the optimal therapeutic strategy remains uncertain, especially in recurrent and metastatic disease.

Conclusions

The clinical behaviour of well-differentiated MeNETs is often indolent and benign, but a subset of these neoplasms follow an aggressive clinical course with metastatic disease and sometimes tumour-related death, even after an initial period of seemingly benign behaviour. As of yet, there are no known clinicopathological factors that can predict malignant transformation of MeNETs. Surgery is the preferred treatment modality of primary MeNETs. Because of the possibility of recurrence and metastatic disease even after a prolonged period of time after initial presentation, we recommend to perform a comprehensive diagnostic work-up to identify possible metastases at initial presentation, and perform meticulous and prolonged follow-up even in patients who underwent seemingly successful treatment of the primary MeNET.

Conflict of interest statement

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Funding

This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Author contributions

All authors contributed equally to this manuscript.

Ethical consideration

This study was approved by the Institutional Ethics Committee Amsterdam UMC Hospital (approval number/protocol number IRB00002991). The research was conducted ethically, with all study procedures being performed in accordance with the requirements of the World Medical Association’s Declaration of Helsinki. Written informed consent was obtained from each participant/patient for study participation and data publication.

History

Received: January 12, 2025

Accepted: June 19, 2025

Figures and tables

Figure 1. CT and MR imaging of the middle ear neuroendocrine tumours of patient 1 (A and B) and patient 2 (C and D). A) Axial T1-weighed MRI scan, demonstrating the primary tumour as a mass in the left mastoid with extension to the temporal fossa and preauricular region; B) Axial temporal bone CT, showing soft tissue in the left middle ear cavity with suspicion of erosion of the malleus and anterior temporal bone; C) Axial T1-weighed MRI scan, demonstrating the recurrent right middle ear mass at the level of the cochlea; D) Axial temporal bone CT, showing soft tissue completely filling in the right middle ear cavity.

Figure 2. Histopathological findings (haematoxylin and eosin) of the (A) primary middle ear tumour and (B) liver metastasis of patient 1. In both tumours features of middle ear neuroendocrine tumours can be observed: atypical epithelial cells with a cribriform growth pattern associated with fibrous stroma in the background. The tumour cells showed mild pleiomorphism, sporadic nucleoli and sparse eosinophilic cytoplasm. Immunohistochemical stains for synaptophysin show strong positivity within tumour cells. Mitoses were not seen and Ki-67 (MIB-1) staining showed < 2% positive tumour cells in both the primary tumour (C) and liver metastasis (D).

References

- Engel M, van der Lans R, Jansen J. Management and outcome of middle ear adenomatous neuroendocrine tumours: a systematic review. Oral Oncolog. 2021;121. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.oraloncology.2021.105465

- Mooney E, Dodd L, Oury T. Middle ear carcinoid: an indolent tumor with metastatic potential. Head Neck. 1999;21:72-77. doi:https://doi.org/10.1002/(SICI)1097-0347(199901)21:1<72::AID-HED10>3.0.CO;2-G

- Ramsey M, Nadol J, Pilch B. Carcinoid tumor of the middle ear: clinical features, recurrences, and metastases. Laryngoscope. 2005;115. doi:https://doi.org/10.1097/01.mlg.0000175069.13685.37

- Pellini R, Ruggieri M, Pichi B. A case of cervical metastases from temporal bone carcinoid. Head Neck. 2005;27:644-647. doi:https://doi.org/10.1002/hed.20197

- Gaafar A, Ereno C, Ignacio Lopez J. Middle-ear carcinoid tumor with distant metastasis and fatal outcome. Hematol Oncol Stem Cell Ther. 2008;1:53-56. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/S1658-3876(08)50061-6

- Tabuchi K, Aoyagi Y, Uemaetomari I. Carcinoid tumours of the middle ear. J Otolaryngol Neck Surg. 2009;38:E91-94.

- Salzman R, Starek I, Ticha V. Metastasizing middle ear carcinoid: an unusual case report, with focus on ultrastructural and immunohistochemical findings. Otol Neurotol. 2012;33:1418-1421. doi:https://doi.org/10.1097/MAO.0b013e3182693888

- Fundakowski C, Chapman J, Thomas G. Middle ear carcinoid with distant osseous metastasis. Laryngoscope. 2013;123:779-782. doi:https://doi.org/10.1002/lary.23434

- Bell D, El-Naggar A, Widley P. Middle ear adenomatous neuroendocrine tumors: a 25-year experience at MD Anderson Cancer Center. Virchows Arch. 2017;471:667-672. doi:https://doi.org/10.1007/s00428-017-2155-6

- Van der Lans R, Engel M, Rijken J. Neuroendocrine neoplasms of the middle ear: unpredictable tumor behaviour and tendency of recurrence. A single centre experience with nine patients. Head Neck. 2021;43:1-6. doi:https://doi.org/10.1002/hed.26658

- Alciato L, Lahlou G, Tankéré F. Middle ear adenomatous neuroendocrine tumours: single institution experience with five cases. Clin Otolaryngol. 2021;46:1136-1141. doi:https://doi.org/10.1111/coa.13791

- Pollastri F, Pecci R, Pellegrini E. Late onset middle ear neuroendocrine tumor presenting with distant metastasis. Otolaryngology Case Reports. 2021;19. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.xocr.2021.100289

- Ratnayake G, Luong T, Toumpanakis C. Middle ear neuroendocrine tumours: insight into their pathogenesis, diagnosis and management. J Neuroendocrinol. 2021;33. doi:https://doi.org/10.1111/jne.13031

- Fisch U, Mattox D. Microsurgery of the Skull Base. Georg Thieme Verlag; 1988.

- Rindi G, Klimstra D, Abedi-Ardekani B. A common classification framework for neuroendocrine neoplasms: an International Agency for Research on Cancer (IARC) and World Health Organization (WHO) expert consensus proposal. Mod Pathol. 2018;31:1770-1786. doi:https://doi.org/10.1038/s41379-018-0110-y

- Miller H, Drymousis P, Flora R. Role of Ki-67 proliferation index in the assessment of patients with neuroendocrine neoplasias regarding the stage of disease. World J Surg. 2014;38:1353-1361. doi:https://doi.org/10.1007/s00268-014-2451-0

- Singh S, Hallet J, Rowsell C. Variability of Ki67 labeling index in multiple neuroendocrine tumors specimens over the course of the disease. Eur J Surg Oncol. 2014;40:1517-1522. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejso.2014.06.016

- Asa S, Arkun K, Tischler A. Middle ear “adenoma”: a neuroendocrine tumor with predominant L cell differentiation. Endocr Pathol. 2021;32:433-441. doi:https://doi.org/10.1007/s12022-021-09684-z

- Del Rivero J, Perez K, Kennedy E. Systemic therapy for tumor control in metastatic well-differentiated gastroenteropancreatic neuroendocrine tumors: ASCO guideline. JCO. 2023;41:5049-5067. doi:https://doi.org/10.1200/JCO.23.01529

- Pavel M, Baudin E, Couvelard A. ENETS consensus guidelines for the management of patients with liver and other distant metastases from neuroendocrine neoplasms of foregut, midgut, hindgut, and unknown primary. Neuroendocrinology. 2012;95:157-176. doi:https://doi.org/10.1159/000335597

- Lee J, Choi J, Choi C. Role of radiotherapy for pancreatobiliary neuroendocrine tumors. Radiat Oncol J. 2013;31:125-130. doi:https://doi.org/10.3857/roj.2013.31.3.125

Downloads

License

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

Copyright

Copyright (c) 2025 Società Italiana di Otorinolaringoiatria e chirurgia cervico facciale

How to Cite

- Abstract viewed - 539 times

- PDF downloaded - 103 times